Making Portraits In Africa, Respectfully

(originally published in Pixel Magazine)

David Blumenkrantz spent years documenting relief and development efforts throughout East and Central Africa. His priority as a photographer was to build trust and respect those in front of his lens.

When photographer David Blumenkrantz arrived back in the United States after his first trip to Africa in 1987, he felt his work was not done. He settled in Kenya until 1994, using Nairobi as his base to travel and make portraits of people. Now, he is preparing the images for publication in a new photobook.

For Polarr, Emily von Hoffmann spoke with Blumenkrantz about the work, and the importance — particularly for a white, western photographer — of creating trust and respectful portraiture. To see the original post which includes photographs, go to Vantage.

Emily von Hoffmann: Can you describe the scope of this book project?

David Blumenkrantz: The book is an anthology of the work I made while living in Kenya from 1987–1994. The nature of my assignments usually took me into some pretty remote locations in several countries in East and Central Africa including Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire), Tanzania, Eritrea and Chad.

A large segment of the images were made for the media, mostly Kenyan publications. A lot of the political topics covered in the book came from this media work, but a lot of it also just came from my own curiosity and self-interest in politics.

Generally speaking, the vast majority of what ended up in the book could be considered environmental portraits. I happened to land in Africa, but no matter where I am I’m driven by a fascination with the human condition, trying to make some sort of connection to people through my photographs. So the book is largely a reflection of this interest in common people, and how they exist within and beyond the circumstances they find themselves in.

“My hope is always that I don’t make the people I photograph feel like bugs under a microscope, but rather like autonomous individuals presenting themselves to the lens.”

EvH: Tell me about your first trip to Africa. Did you have this project in mind then? If not, what brought you there?

DB: I first travelled to Africa in January 1987, to document projects for NGOs involved in relief and development projects. Water engineering, education, health care, refugee life and so on. The six-week trip took me through Zaire, Kenya and Sudan. It was a life-changing experience, filled with revelations, tears and laughter. I shot dozens of rolls of film on my fully manual Nikons.

By the time the trip ended I knew I couldn’t just go back to the life I had been living in Los Angeles; I wanted to move to Africa and work there as long as I could. Of course, at the time I wasn’t thinking about any long-term projects, but from the beginning I started shooting portraits and developing my personal projects.

EvH: You’ve written that portraits should be a collaboration between subject and photographer. What does that look like in practice?

DB: It’s sometimes difficult to tell which portrait is the result of a very collaborative and interactive session, and which is the result of a furtive encounter, or maybe something between these two. It’s not always obvious in the end result.

Speaking for myself, a collaboration occurs when there is at least some tacit approval by a subject. It might take a verbal explanation, but sometimes there is an unspoken understanding and permission. Ideally there’s an understanding that the act of recording one’s likeness is for posterity, or because they might represent the human face of whatever the situation is that brought you there. This collaboration, when it occurs, might [equally] be the result of an established relationship in which the photographer and subject know each other pretty well.

It may result after having had your motives explained by a third party. Then again it is entirely possible to record something that seems essential and authentic even in a fleeting instance. Often it is just the subject’s gaze toward the camera that can give the viewer of the photograph the feeling of connection with the subject.

If you look at a project like Avedon’s American West, you can sort of pick up on how comfortable or uncomfortable people feel about what is happening with the photographer. My hope is always that I don’t make the people I photograph feel like, or end up appearing like, bugs under a microscope, but rather like autonomous individuals presenting themselves to the lens.

“It’s important to recognize the sacrifices that many make, Africans included, in the name of reporting and storytelling.”

EvH: What are some other specific things that you do to create a respectful interaction or environment with portrait subjects, particularly when you’re a white, western photographer trying to avoid voyeurism or mere tourism in your work?

DB: Situations vary — when appearing out of the blue in some remote rural settlement in northern Kenya, the Shaba Province of Zaire or the deserts of northern Sudan it helps a lot if you are a representative of the NGO or other organization that has an established presence there, and is hopefully respected and appreciated by the community.

In those instances much of the work of creating the respectful, thoughtful environment is in place and you can move forward with people in that context. Coming in as a media representative, or just as an interested individual can be more of a challenge.

The naïve idealism and notions of universal brotherhood I first brought to Africa ultimately wore thin, and what it comes down to is simple, genuine human interest and respect. I generally find that people are receptive if they sense that my motivations for being there are honorable, and I’m not coming off as a voyeur, or worse the “white savior” following in a long line of colonial, missionary and even anthropological exploitation.

My desire and willingness to assimilate — learning Kiswahili and other tribal languages, sharing with delight in the food, music and stories — always served me well. People, regardless of their education or cultural background, can sense when they are being used. You’ll see suspicion in their eyes in certain photographs if you haven’t done enough to cross barriers. You’ll never convince everybody to trust your motives, and I did face my share of resistance.

This was made frightfully clear to me when I decided to venture into the poorer sections of Nairobi during the Saba Saba multiparty democracy riots in 1990, and was swept up and detained by police. Held for questioning for several hours, I was relieved to be released unscathed and uncharged, knowing that colleagues of mine from other news agencies had not been so lucky.

In this spirit I’ve written a dedication to the book honoring Hos Maina, the Kenyan news photographer killed along with three others, including the more publicized Dan Eldon, by a mob in Somalia in 1993. It’s important to recognize the sacrifices that many make, Africans included, in the name of reporting and storytelling.

EvH: Can you describe one or two of your favorite images, and the situation surrounding them?

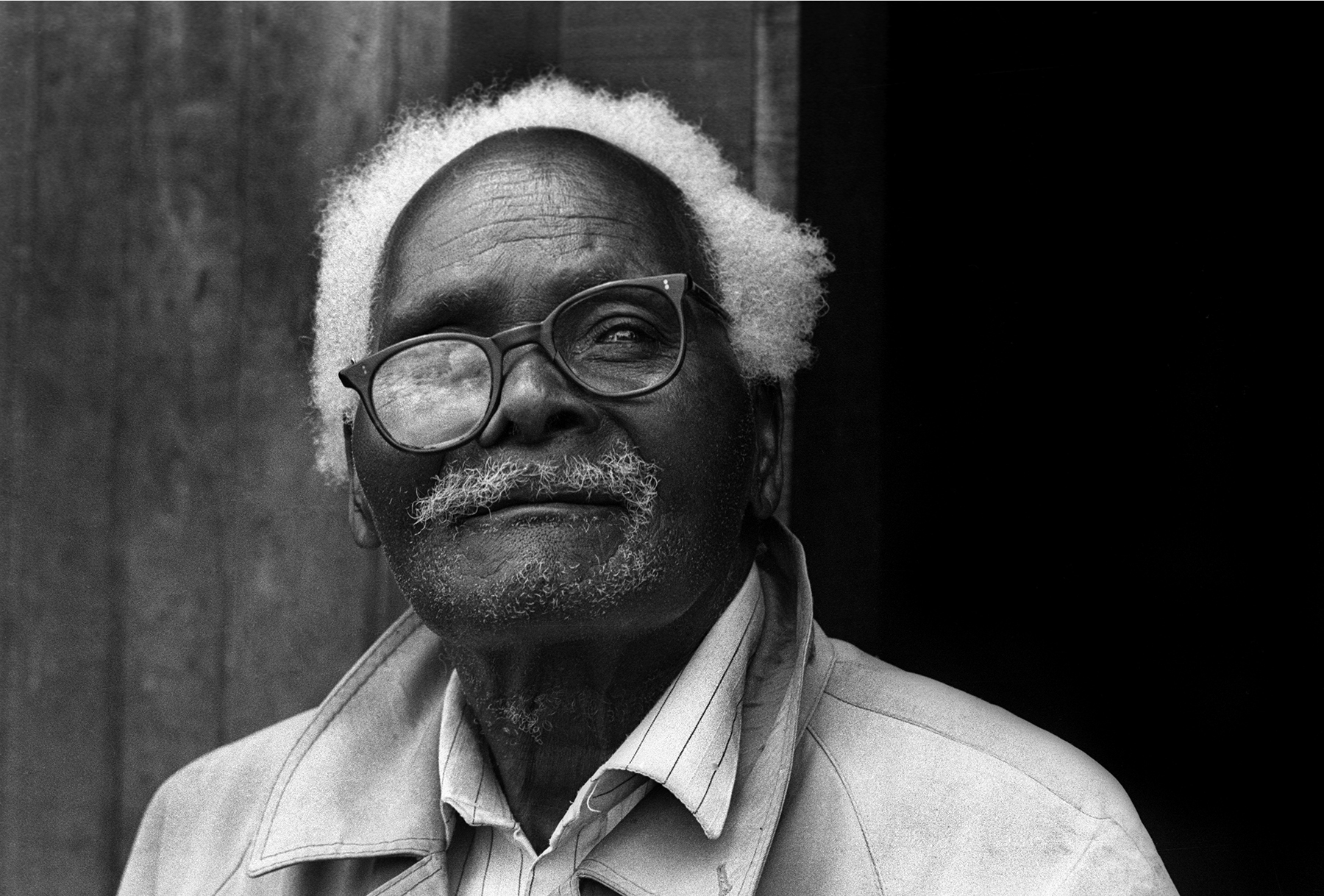

DB: One would have to be the portrait of Mwai, an elderly gentleman (wearing broken glasses). We met at his home in Kamiriithu. I was living nearby, in a little rural town called Rironi at the time, and had been visiting Limuru market, a large open marketplace. I met a guy around my age and after talking awhile he offered to give me a ride back to his homestead in the back of his donkey cart. There I met his grandfather, Mwai, who I learned had once been a leader in the Mau Mau rebellion against British colonial occupation. It was a subject I was very interested in, so having the opportunity meet and talk with Mwai, as well as his son, who had also been in Mau Mau, makes his portrait that much more meaningful.

“People are generally receptive if they sense that my motivations are honorable, and I’m not coming off as a voyeur, or worse the “white savior” following in a long line of colonial, missionary and even anthropological exploitation.”

Another favorite would have to be the portrait I made of the faith healer Nanyonga surrounded by her disciples. Nanyonga made big news in Uganda in 1989 after declaring that she had been visited by God and told that the soil in her humble rural compound was blessed with curative properties. It was at the height of the initial AIDS pandemic in Uganda, and thousands of people were travelling from near and far, including neighboring countries, for a few scoops of her panacea. A friend and I commandeered a company Land Cruiser and made the long journey from Kampala to Nanyonga’s village. The photographs and story of this odd and enlightening encounter are included in the book.

EvH: Who are some people in the book with whom you particularly connected? How did you meet?

DB: There are too many to recount, but a few stand out more than others. Hannah Wanjiru, the woman on the cover of the book was a special friend. We met when I was still with the NGO I originally worked for. Like so many others, Hannah had been born in the beautiful rural villages of Central Kenya but was now mired in abject poverty in the slums of Nairobi. We became friends when I went to visit her family in the Mathare Valley slums, and we remained friends long after I left the NGO.

“The naïve idealism and notions of universal brotherhood I first brought to Africa ultimately wore thin, and what it comes down to is simple, genuine human interest and respect.”

Hannah treated me like a son, and would bring me little gifts such as an African tortoise (which I kept in my flat until leaving the country), and a precious family portrait that showed her as a baby with her parents. I wrote an essay about Hannah and that portrait for the book.

Another noteworthy person who appears in the book is Mercy Gichengi, who I met while working for the Undugu Society of Kenya, advocating on behalf of street children. Mercy was one of many girls I photographed at a shelter we were operating for street girls in a rural town called Rioki. Fortunately she was able to turn her life around, finishing college and becoming an advocate for women and children who need the same love and care that helped her.

“People, regardless of their education or cultural background, can sense when they are being used. You’ll see suspicion in certain photographs if you haven’t done enough to cross barriers.”

A few years ago Mercy and I bumped into each other on social media, and I am happy to call her my friend now. Mercy is writing her own autobiography, and was kind enough to allow me to print an excerpt in the section on street children in my book.

EvH: You’ve photographed social and political scenes in Kenya, Uganda, Chad, the DRC, Eritrea, Sudan, and Tanzania — can you share an important lesson you learned early in your career when navigating these situations?

DB: When faced with situations of political or social unrest, I pretty much tried to operate as openly and transparently as possible, to avoid being accused of having sinister ulterior motives. Of course that’s not always advisable or even possible, and sometimes you want to push the envelope a bit to get away with your photography.

One important lesson is to never take your position or status as a journalist or artist for granted. Not everyone is duly impressed with the badge of honor and sense of duty that gives one his or her sense of purpose.

David Blumenkrantz is a Los Angeles based photographer. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.