You Look Beautiful Like That

The Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe

2002

“Generally speaking, for an African photographer, getting paid is the name of the game. We don’t just pick up a camera for the pure pleasure of it . . . our work stems from an economic need. We learned it from the French . . . It wasn’t the love of the camera that first drew Africans to photography, it was the promise of financial gain and respectable employment. But that first taste turned into a genuine hunger, and a real passion for the art of photography was born.”

* Malick Sidibe, 2000 1

“Whenever I look at my negatives I feel proud of the work I’ve done . . . Frankly, we work in order to earn our daily bread here. When you’re the head of the household it’s your job to make sure you can feed your family! Photography started out as a means to an end to me, (but) I fell head over heels in love with (it), and it’s been a lasting affair.”

* Seydou Keita, 2000 2

The studio portraits of Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe present us with a unique opportunity to consider photography through a non-Western prism. The distinctly African stylings of these two renowned Malian photographers are currently on display at the UCLA Hammer Museum in Westwood.

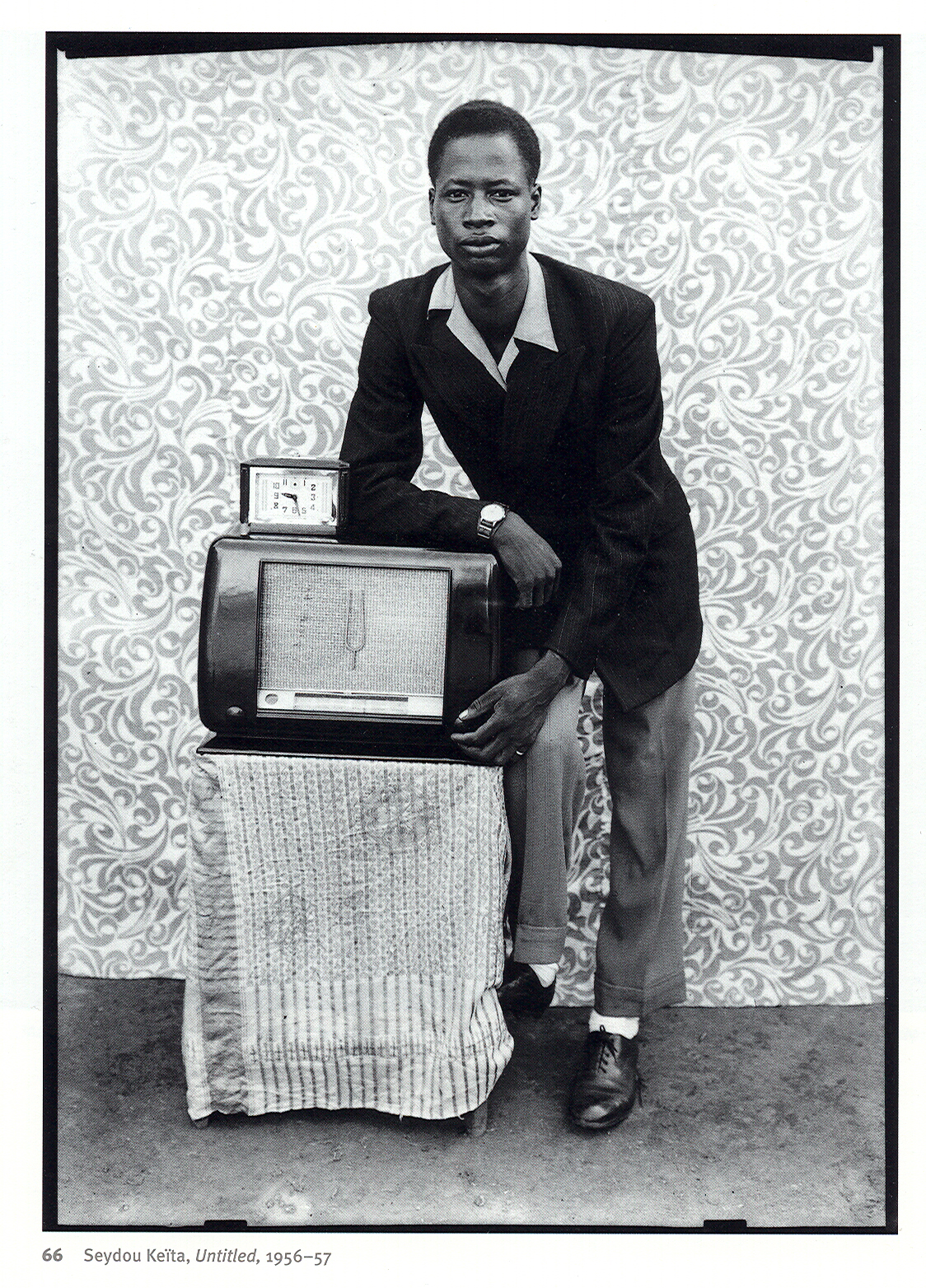

While the presence of universal themes inherent in all portraiture renders these works as comparable in content and form to many of their better known counterparts in the West, such comparisons are essentially superficial. To measure these images against the barometer of Avedon, Penn, Arbus and others of the much-touted Modernist/Fine Art ilk would only skew perspective, understating the uniqueness of their origins. Far better to accept them for what they really represent on the most earthbound level—a wonderful example of the mining of colonial cultural wealth. France's history in Africa is rife with objectionable imperialism, but they rarely did better than inspiring these two artistic souls in Bamako. A particularly seminal example: The ever-probing, relentlessly psychological filter of the Western perspective lends these images a great, though unintended irony. We may look upon images of men posing with radios, clocks or cameras as status symbols, and interpret them as a representation of the temporal, cultural legacy left to colonial Africa. From a singularly African perspective, however, this interpretation may seem irrelevant. To the more defensive critics, they might even seem superfluous, or patronizing. Unintended irony. (a much more detailed explanation of this is needed ).

The fact that both Sidibe and Keita began working in commercial studio photography simply as a means to earn a living isn’t a point to be taken lightly. This remains today a vocational option taken throughout Africa by scores of other entrepreneurial men and women, more often with far less spectacular results. In the booklet accompanying the exhibition, Michelle Lamuniere, a student at Boston University, cites one curator’s platitude: “it is the tension between what Keita’s sitters brought to the portrait session and the pictorial framework that attracts the viewer’s eye.”3 Well, one would be hard-pressed to find a compelling portrait that lacks either of these qualities (where else, after all, than within the pictorial framework?). What could be mentioned here is that what initially attracts the viewer’s eye is the fascination the West has with the Otherness of cultures found in places such as Africa.

In the end, the strength of Keita and Sidibe’s images lies not so much in the craftsmanship or technique they employed, but rather in the simplicity and directness with which the subjects met the gaze of the camera. This was achieved largely due to the democratic, sitter-friendly environment found in most urban and rural studios in the world’s poorer countries. There is little admission of any intention by these photographers to do anything more than create “memories” for their clientele. Ultimately, it must be conceded that the images are given their great weight almost incidentally, and the body of work as a whole constitutes a great documentation of neo-colonial African culture. The portraits by Sidibe, Keita—not to forget countless others who have remained anonymous-- are iconographically defined through the symbols of fashion and technology, so often awkwardly embraced by a people torn between tradition and the desire to adapt to the “modern” world. Otherwise, it is unlikely that these photos would have attracted attention outside of Africa.

1 Lamuniere, Michelle. You Look Beautiful Like That. Cambridge, Yale University Press, 2001. Page 53.

2 Lamuniere, page 44.

3 Lamuniere, page 12.