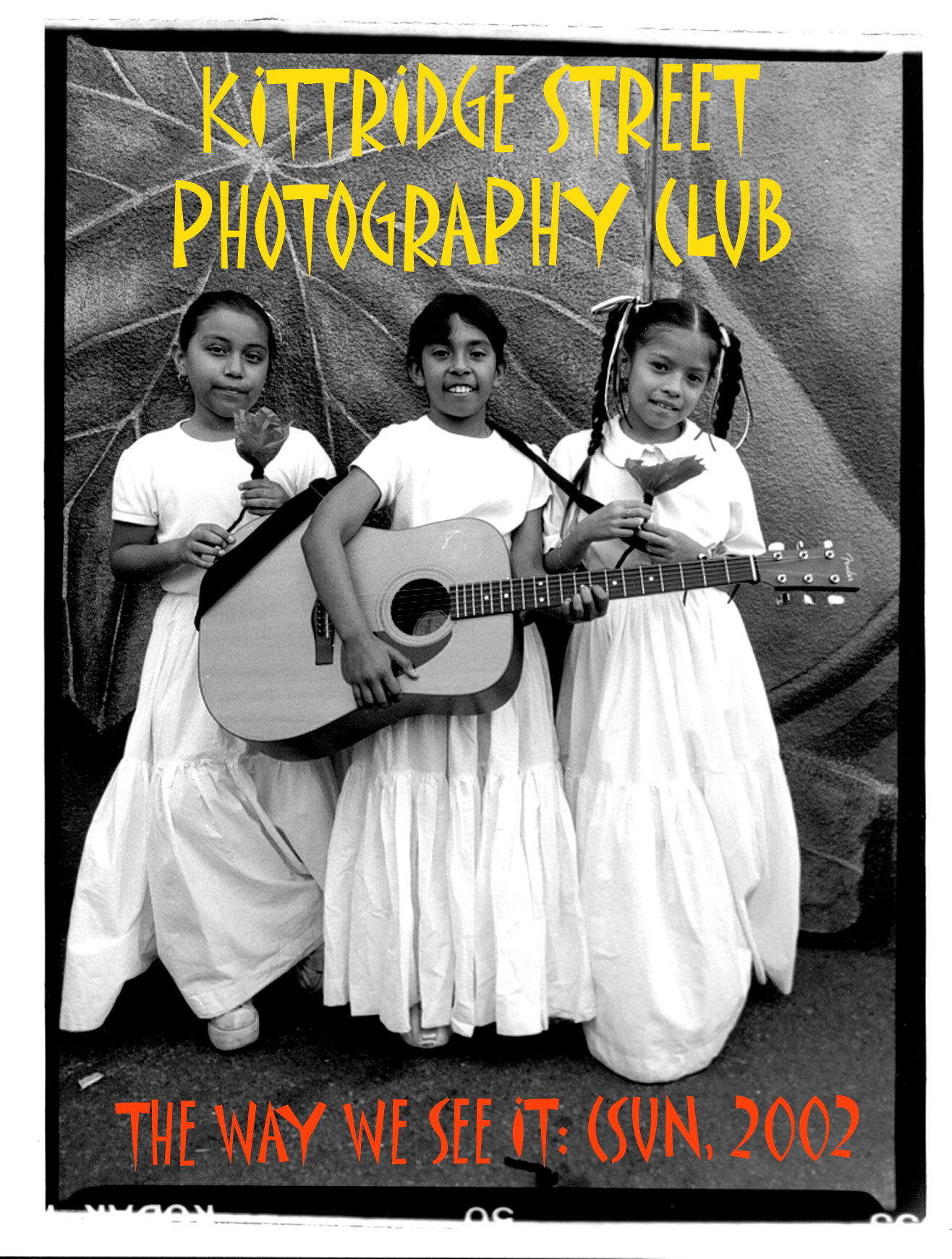

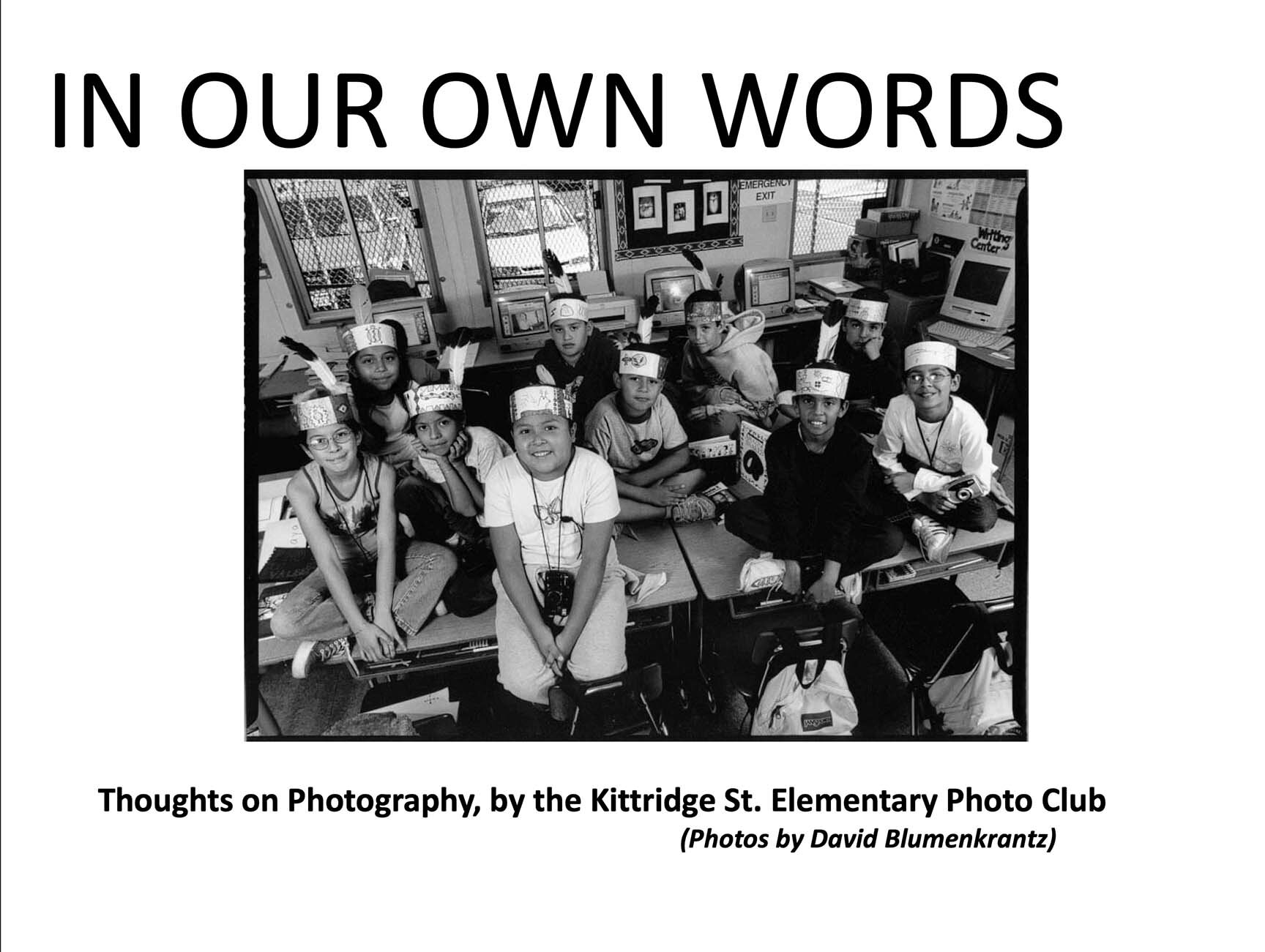

THE WAY WE SEE IT: THE KITTRIDGE ST. ELEMENTARY PHOTO CLUB

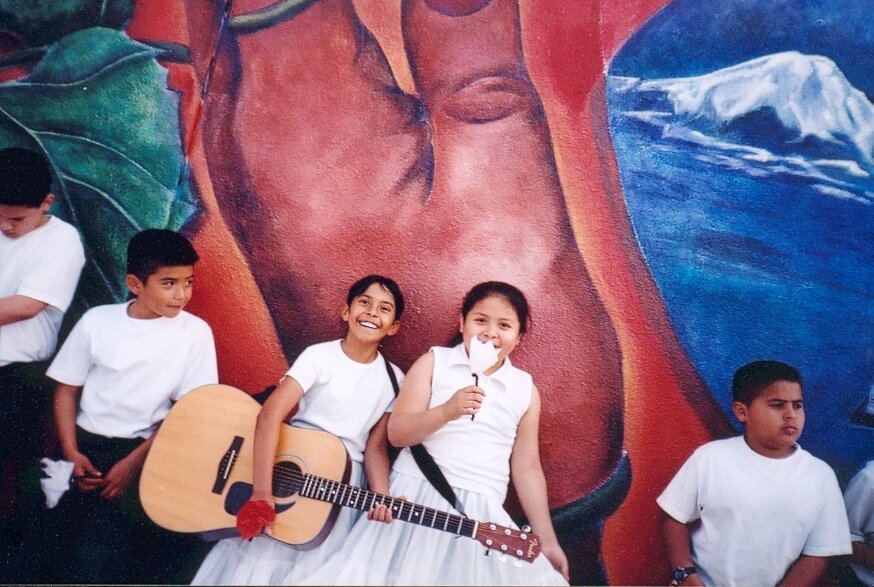

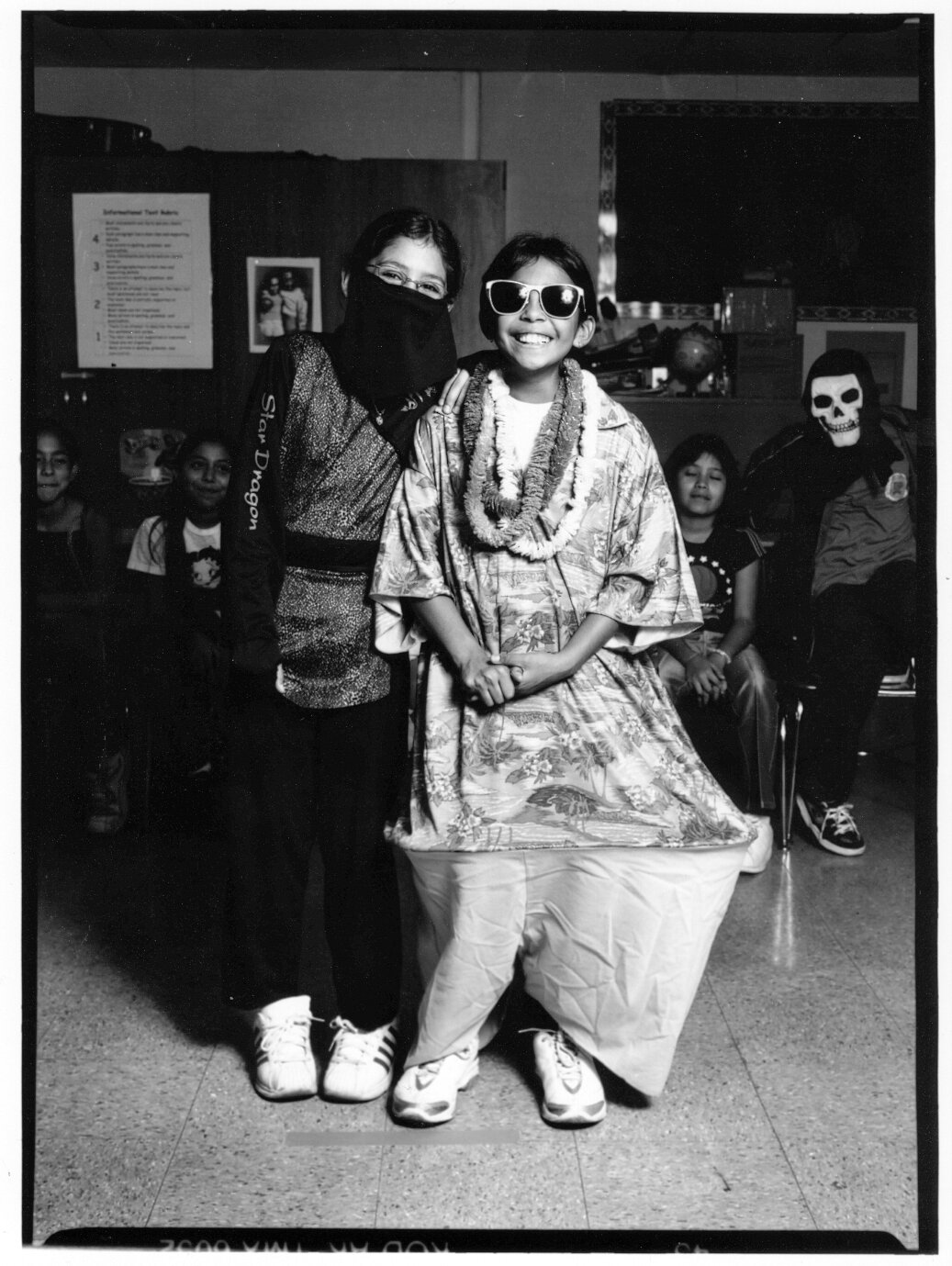

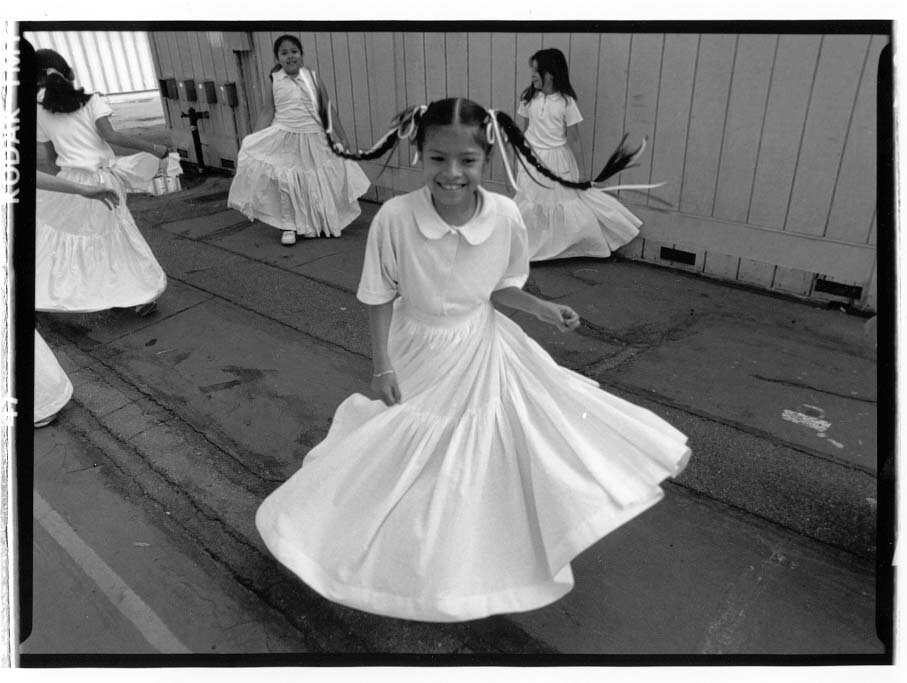

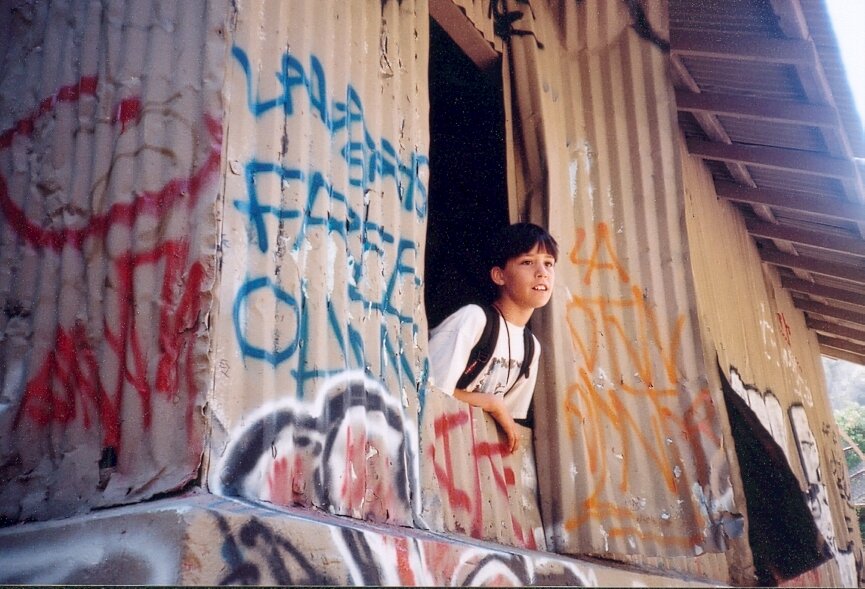

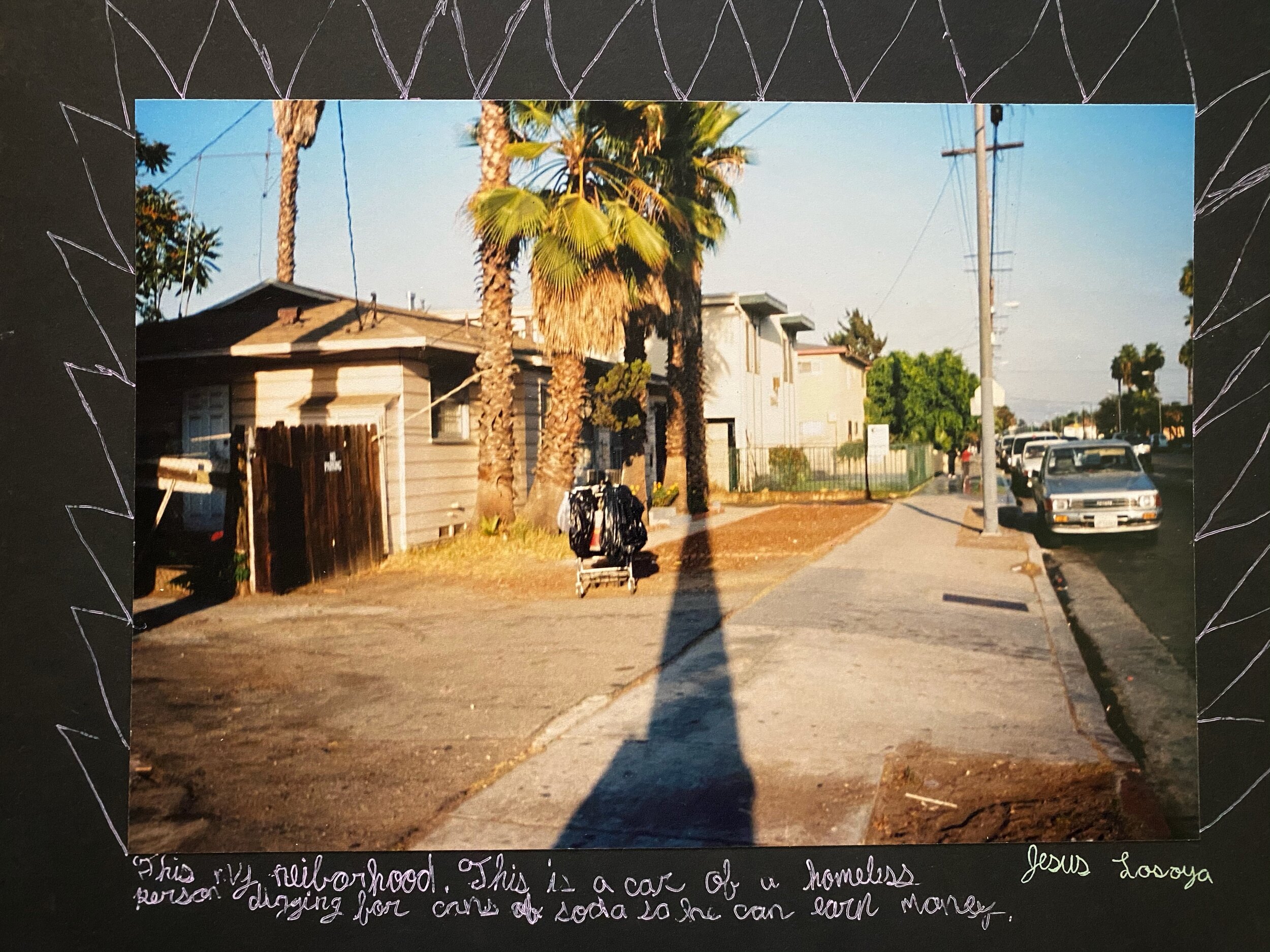

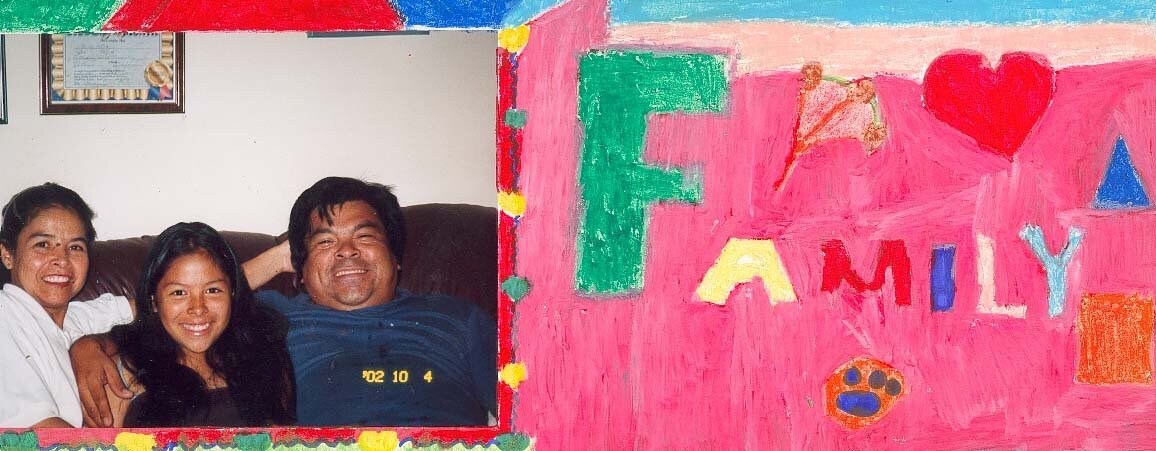

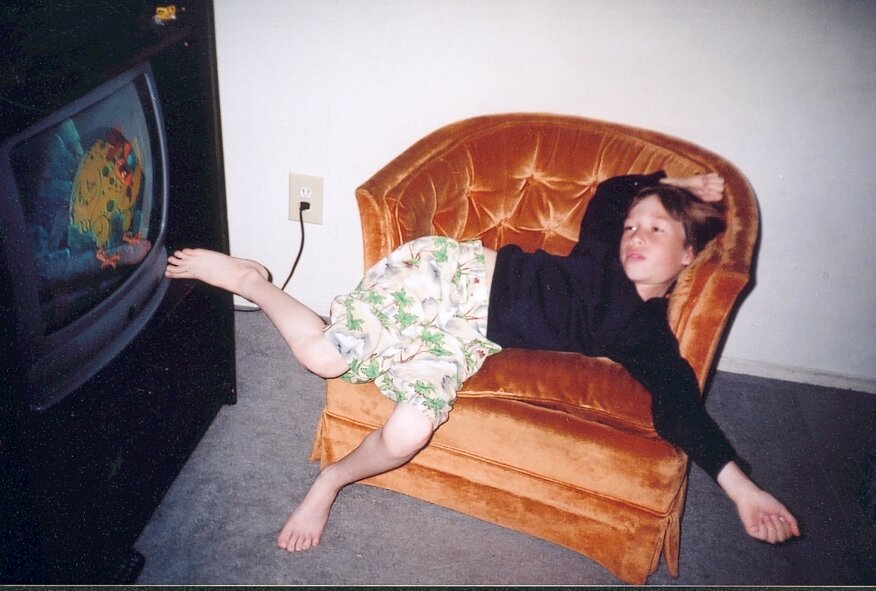

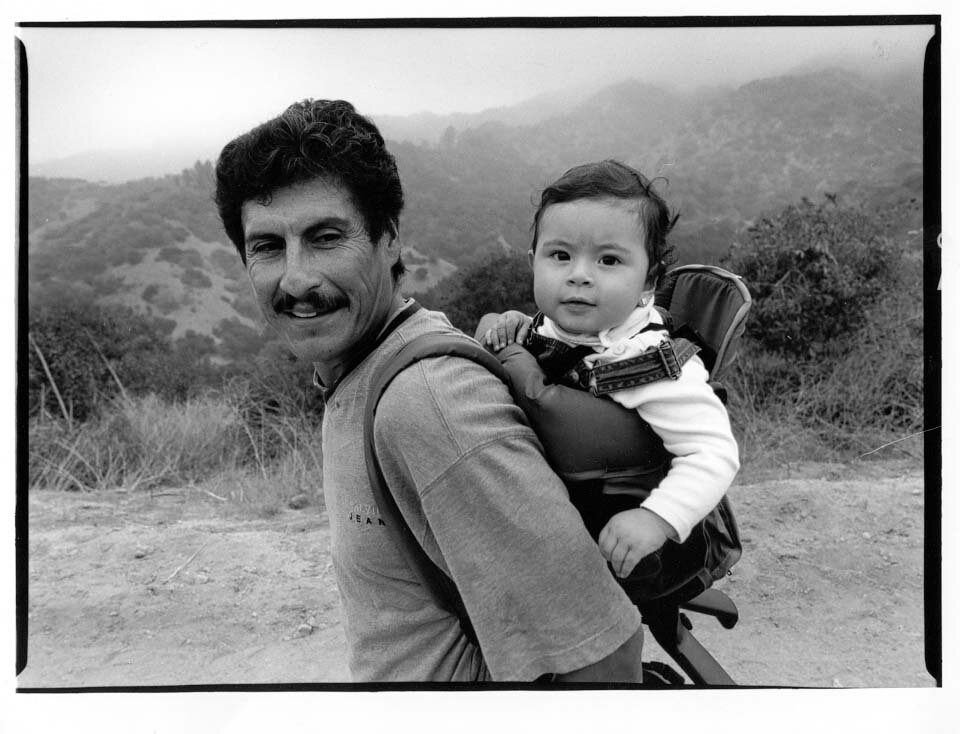

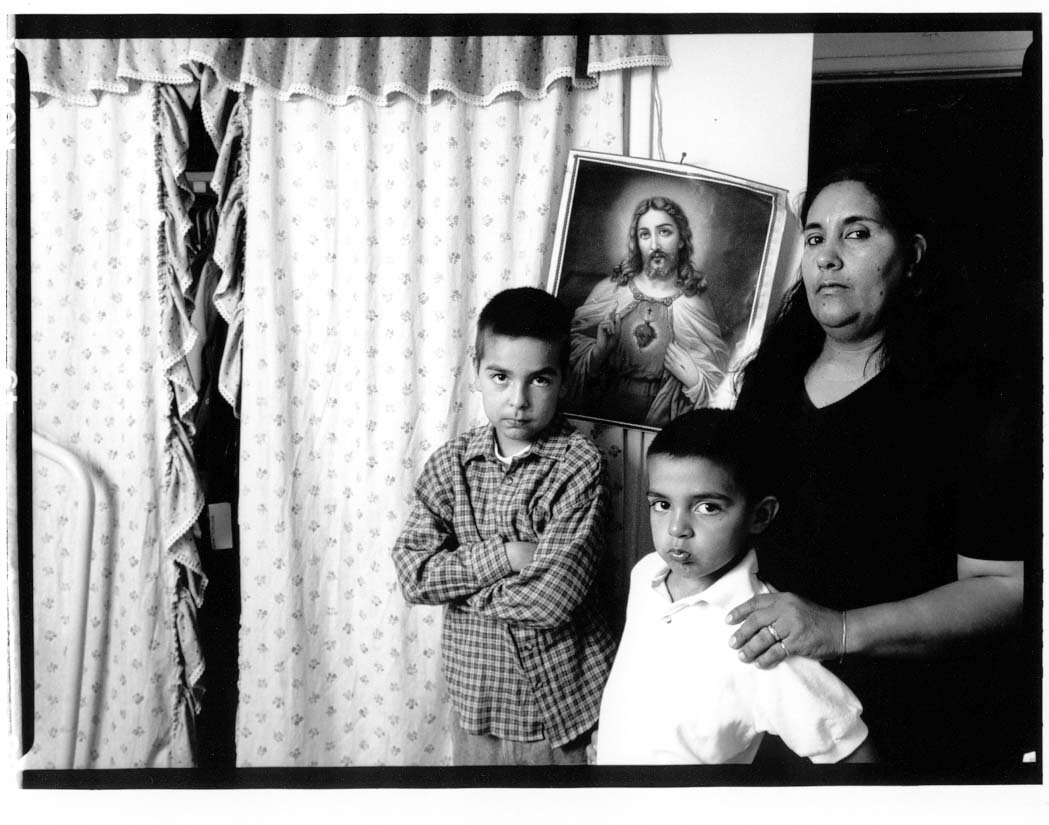

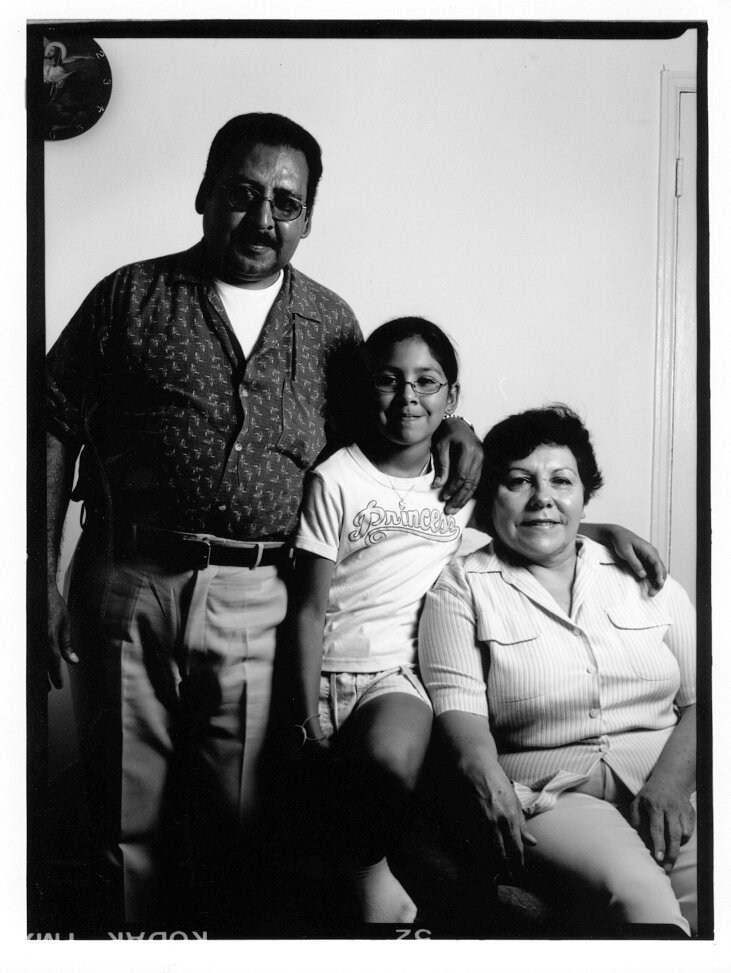

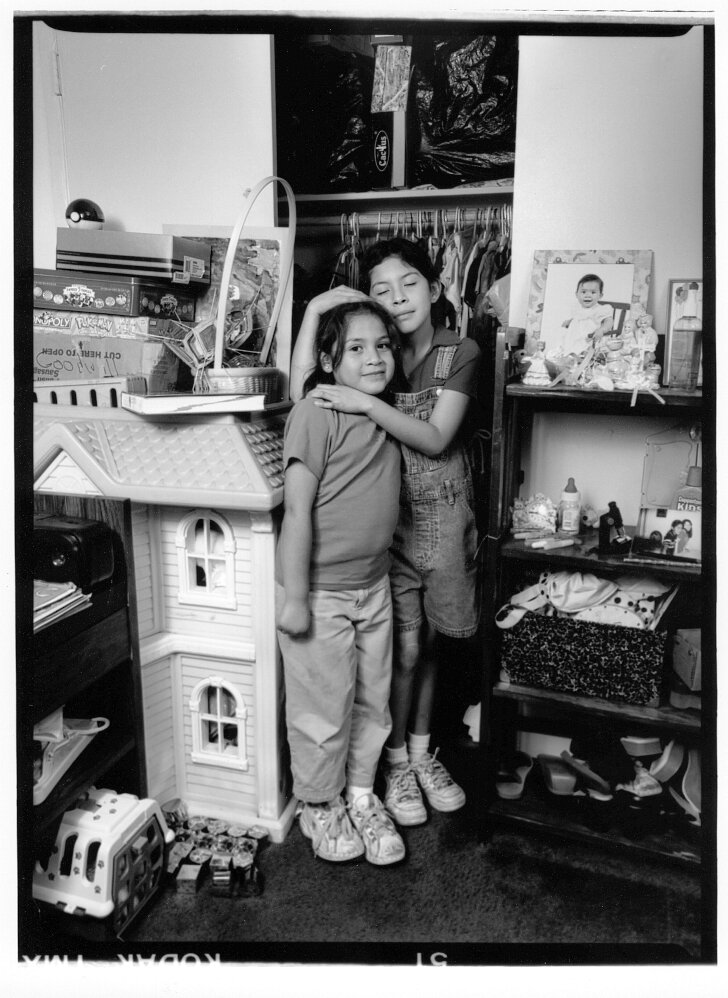

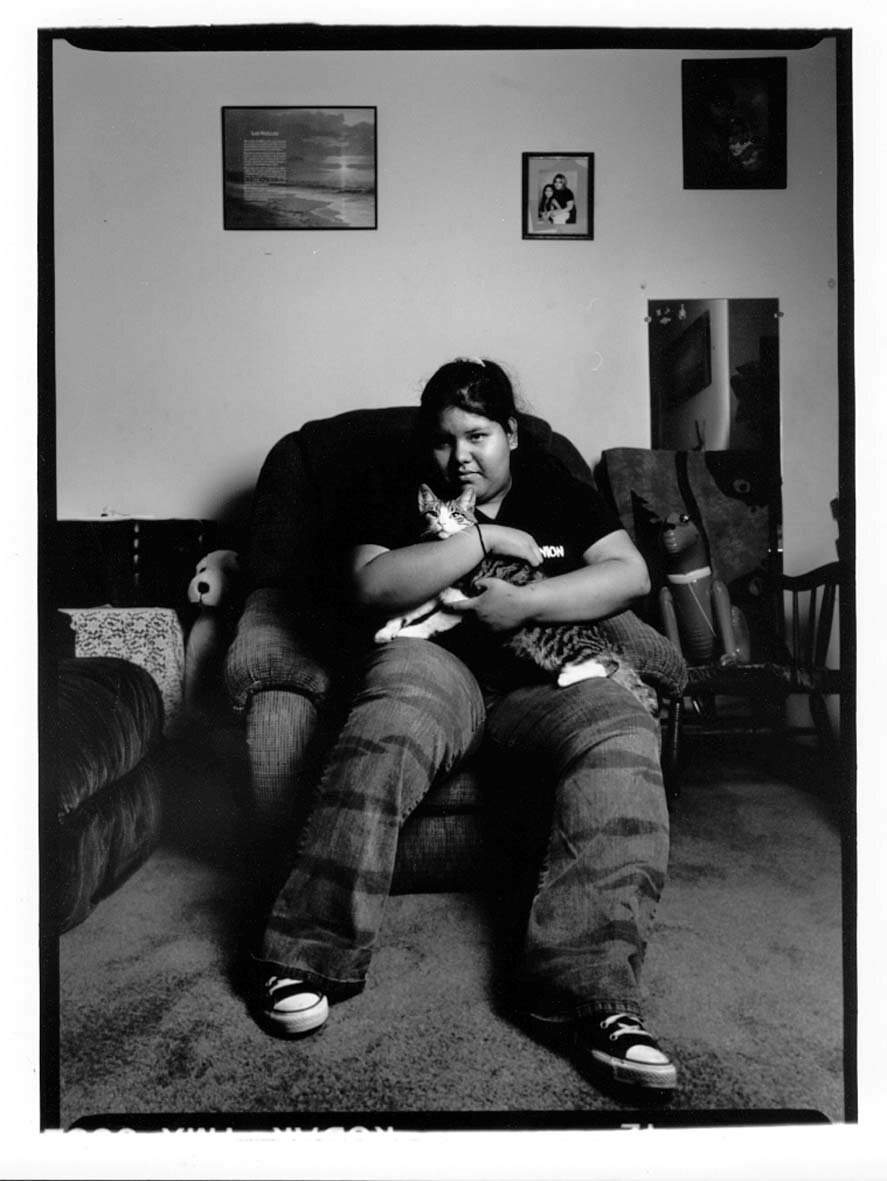

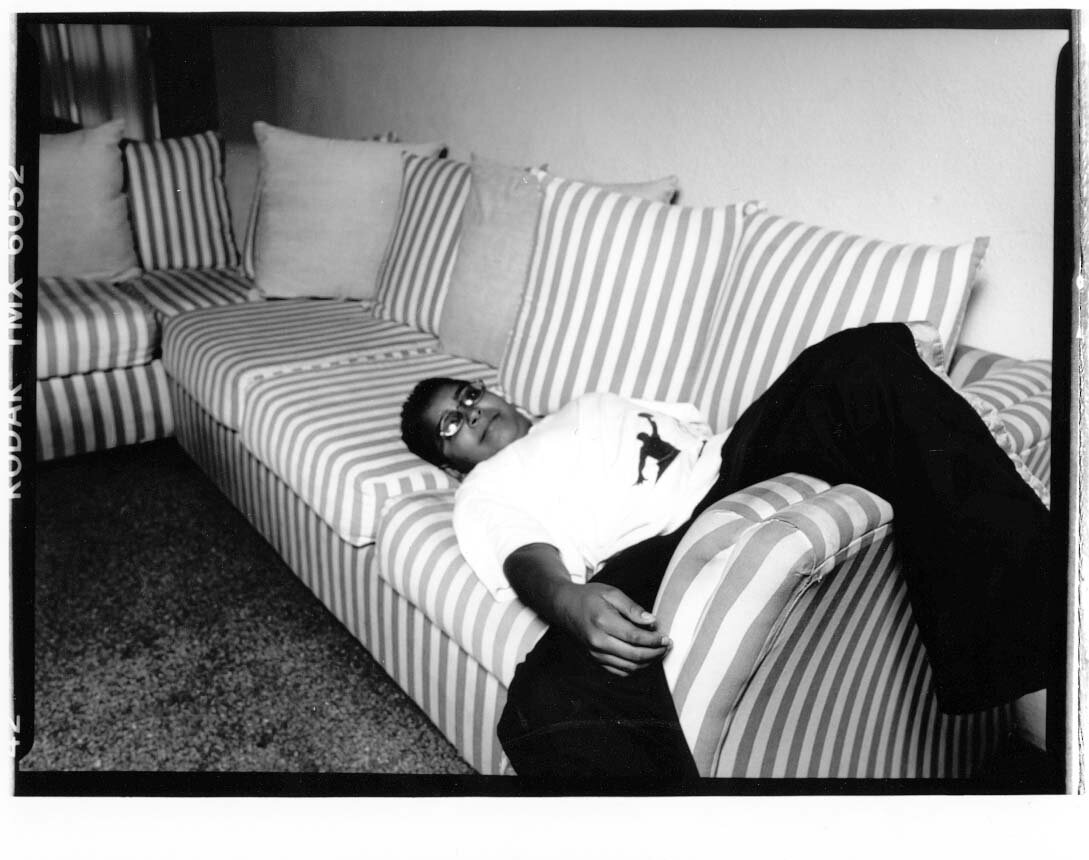

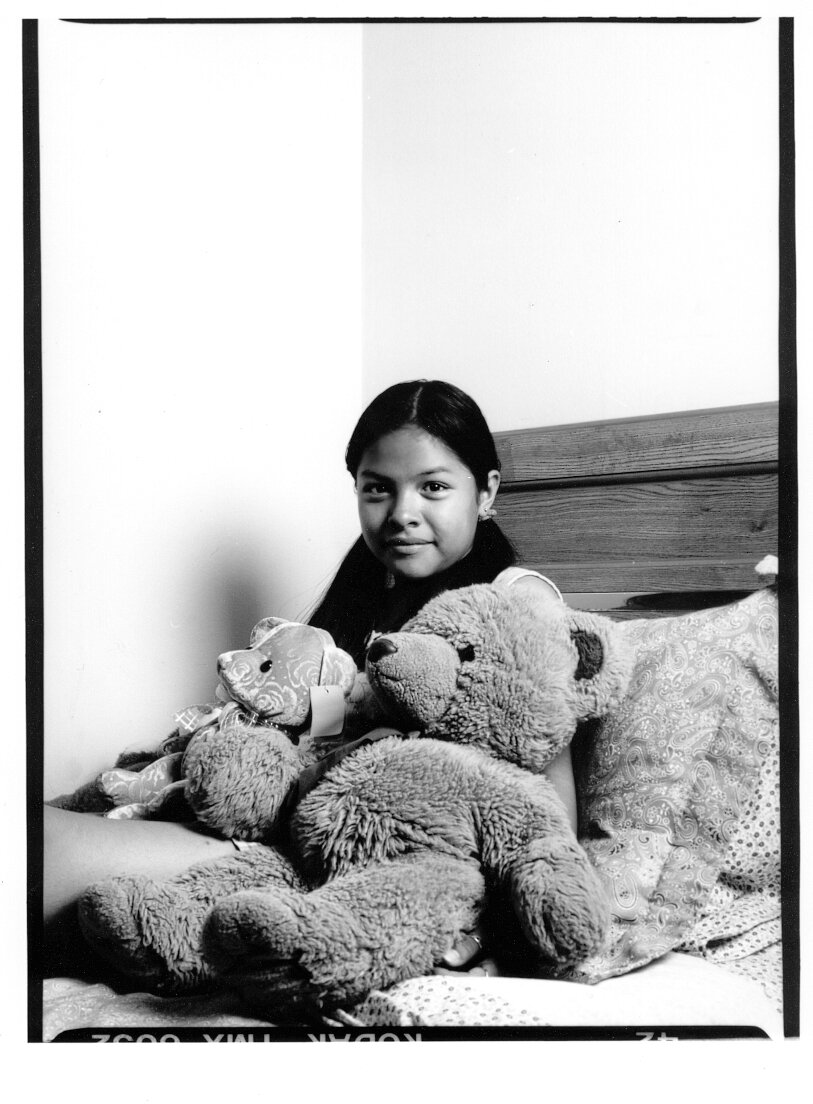

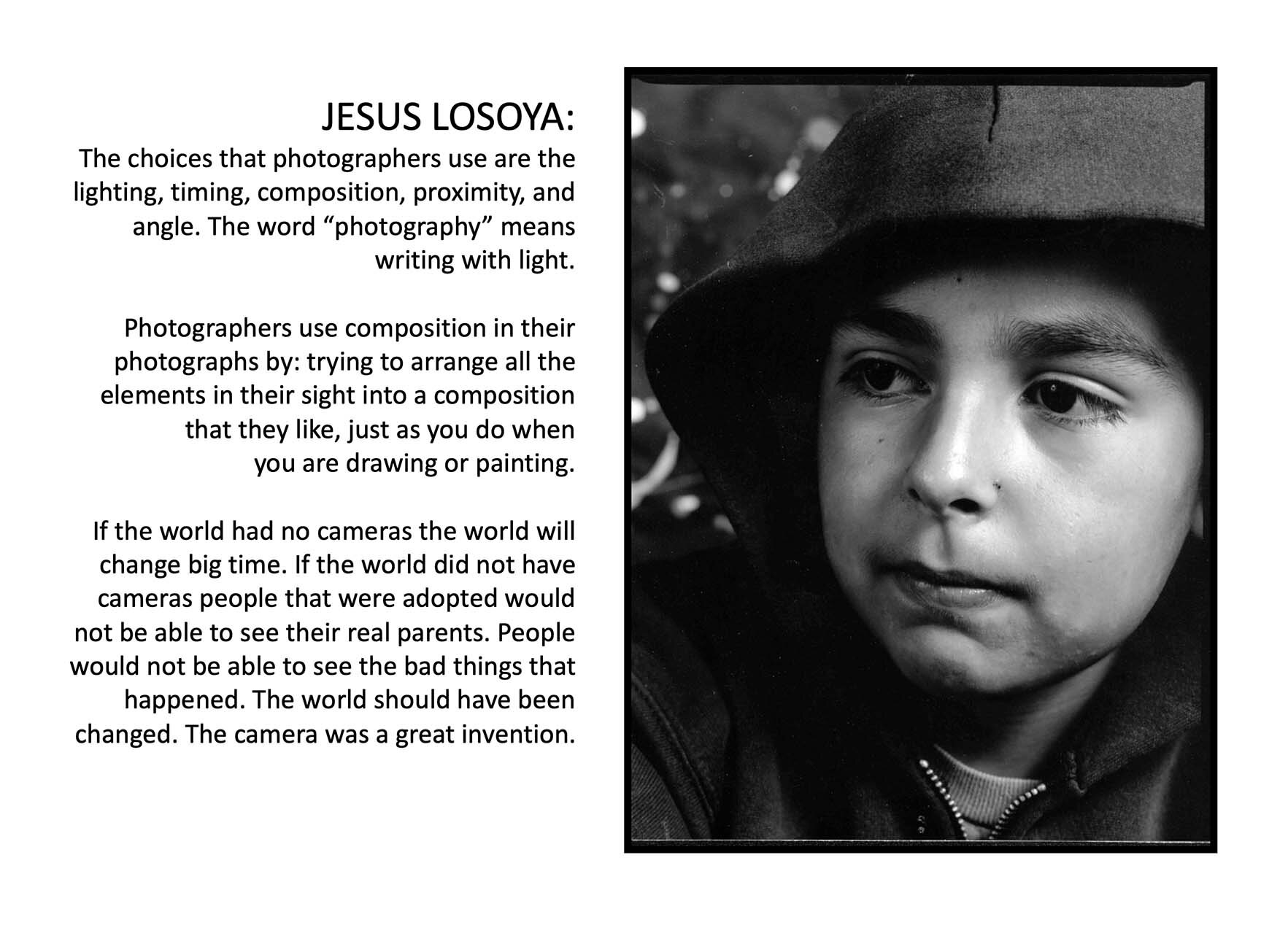

Photograph by Jesus Losyoa

ENTIRE MA THESIS AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD AT SCHOLARWORKS

Excerpted from MA thesis abstract on photography in education

“Photographers use composition in their photographs by trying to arrange all the elements in their sight into a composition that they like, just as you do when you are drawing or painting.”

* Jesus Losoya, age 10

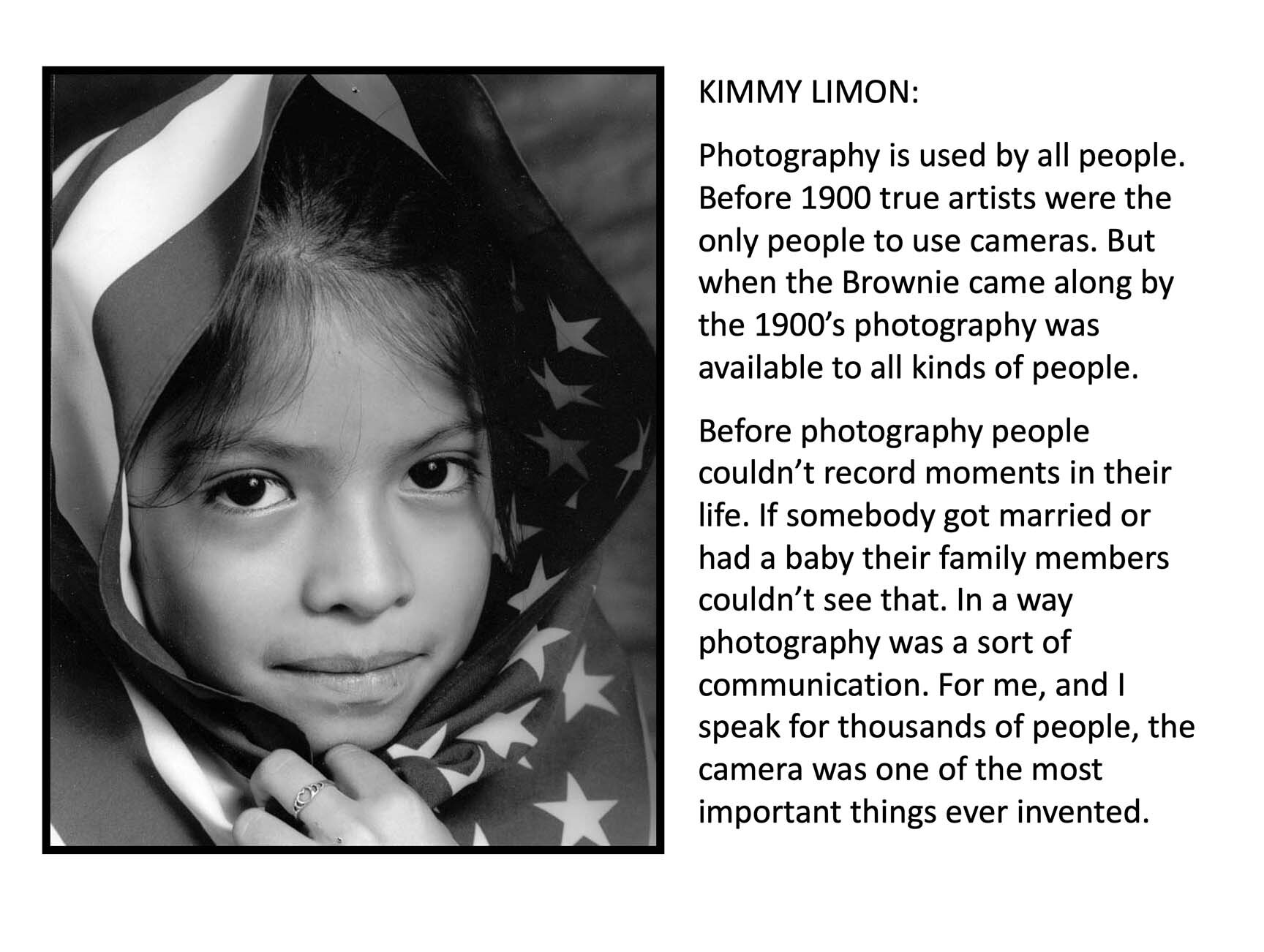

“Photography is used by all people. Before 1900 true artists were the only people to use cameras. But when the Brownie came along by the 1900’s photography was available to all kinds of people. Before photography people couldn’t record moments in their life. If somebody got married or had a baby their family members couldn’t see that. In a way photography was a sort of communication. For me, and I speak for thousands of people, the camera was one of the most important things ever invented.”

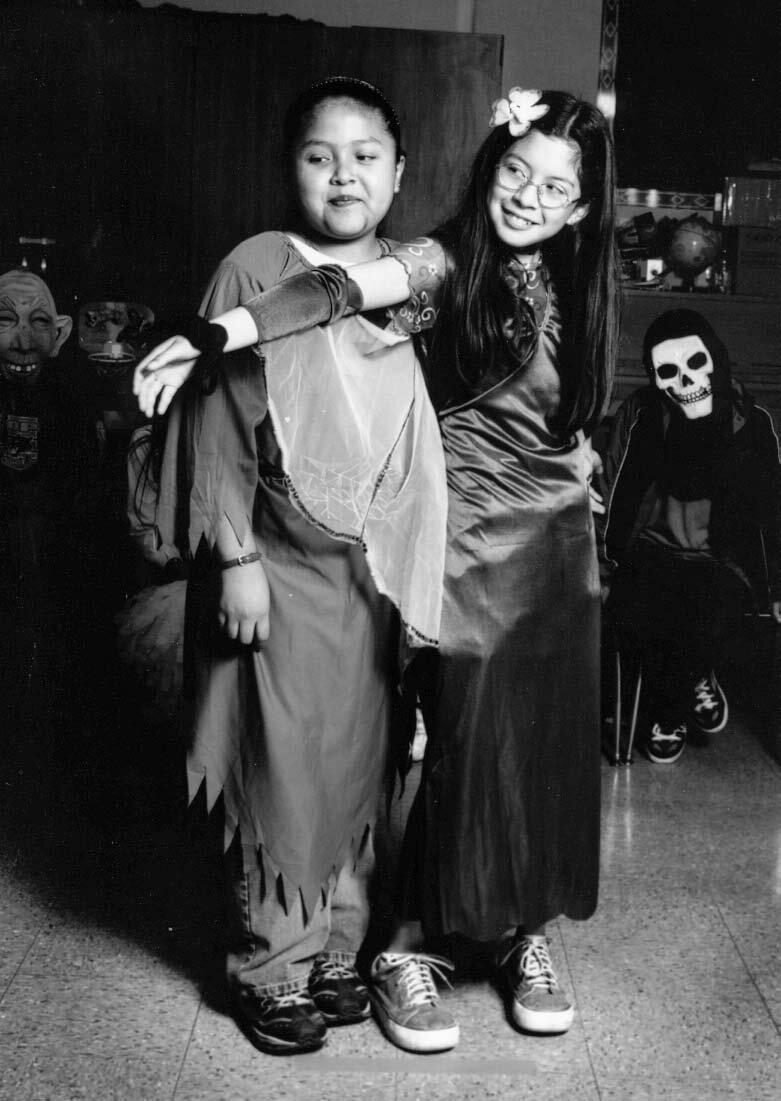

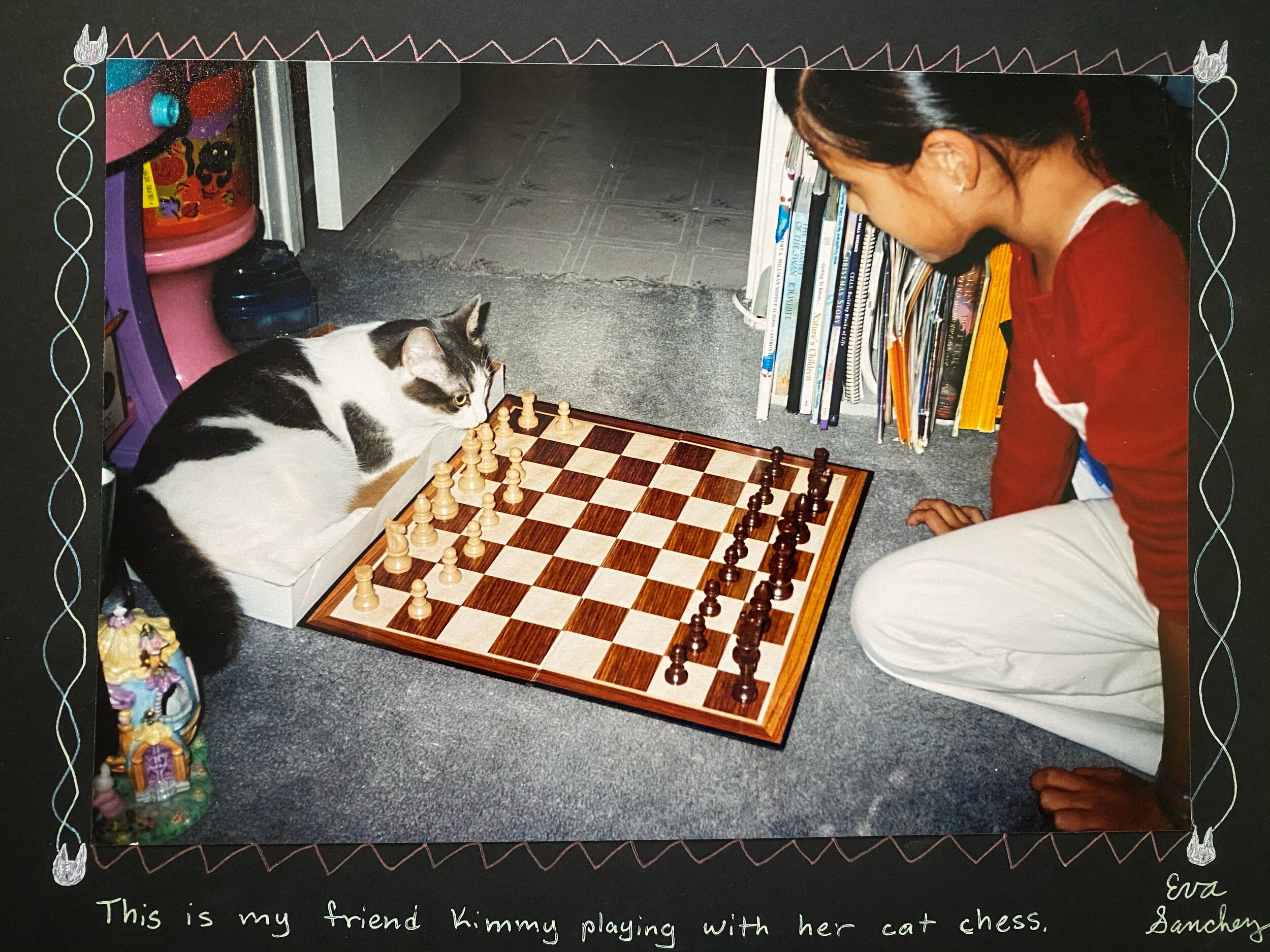

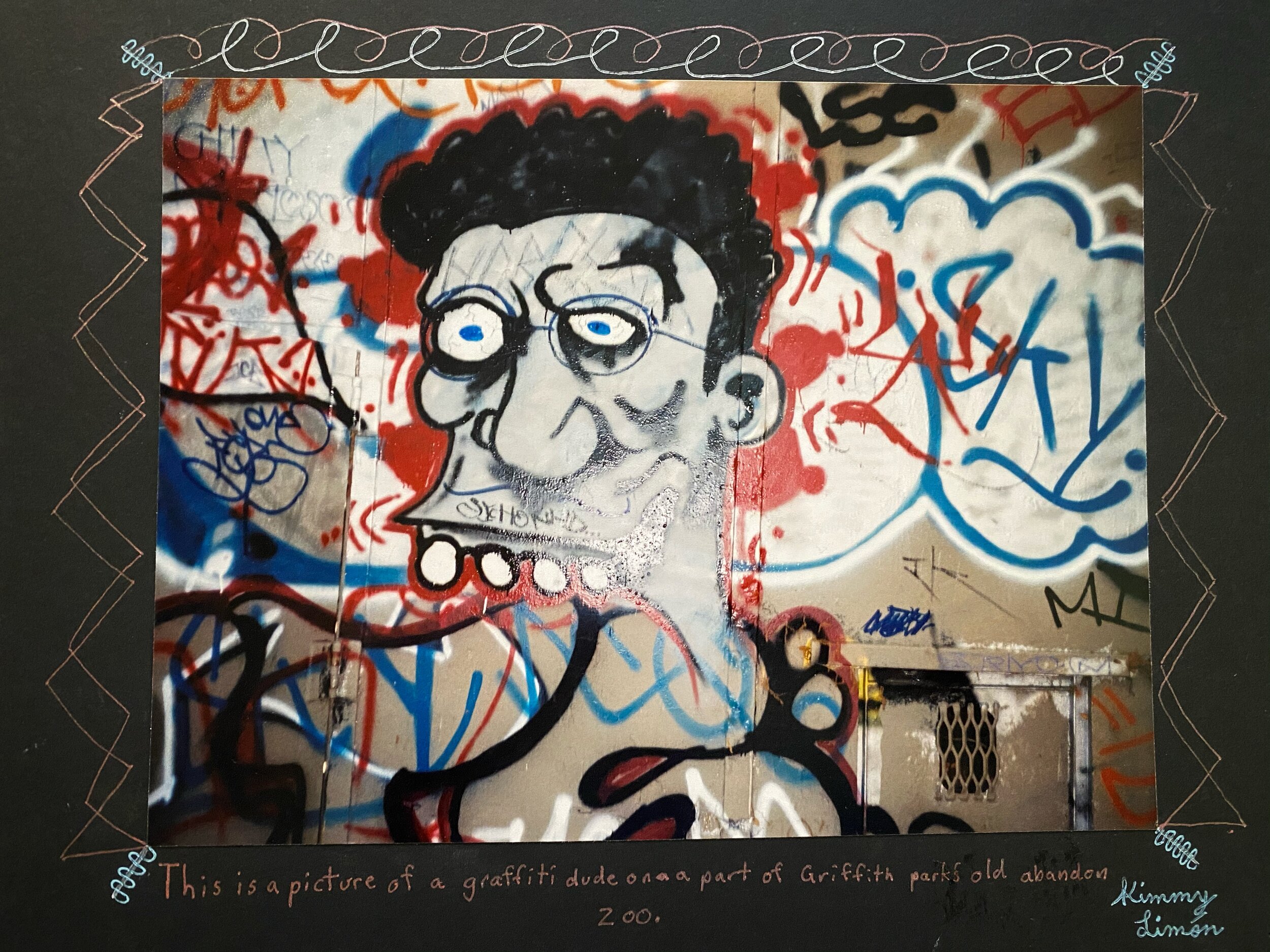

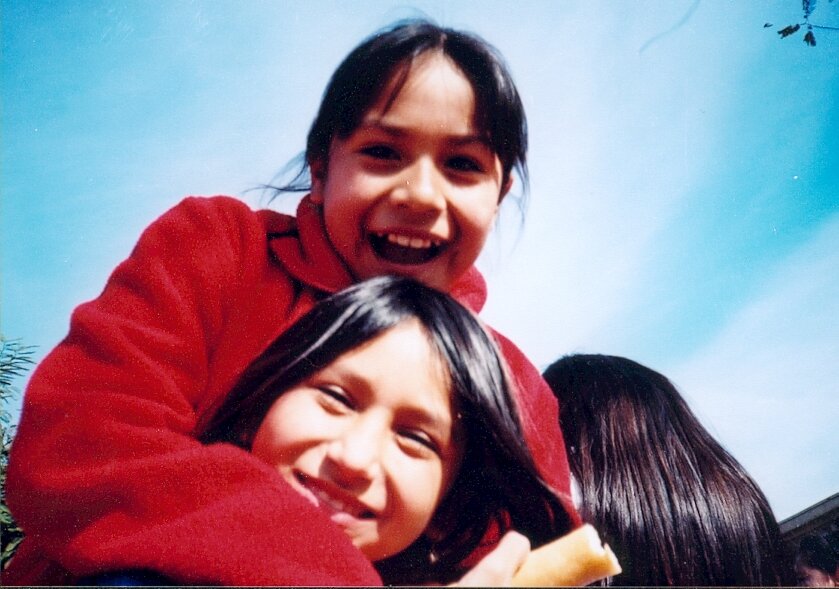

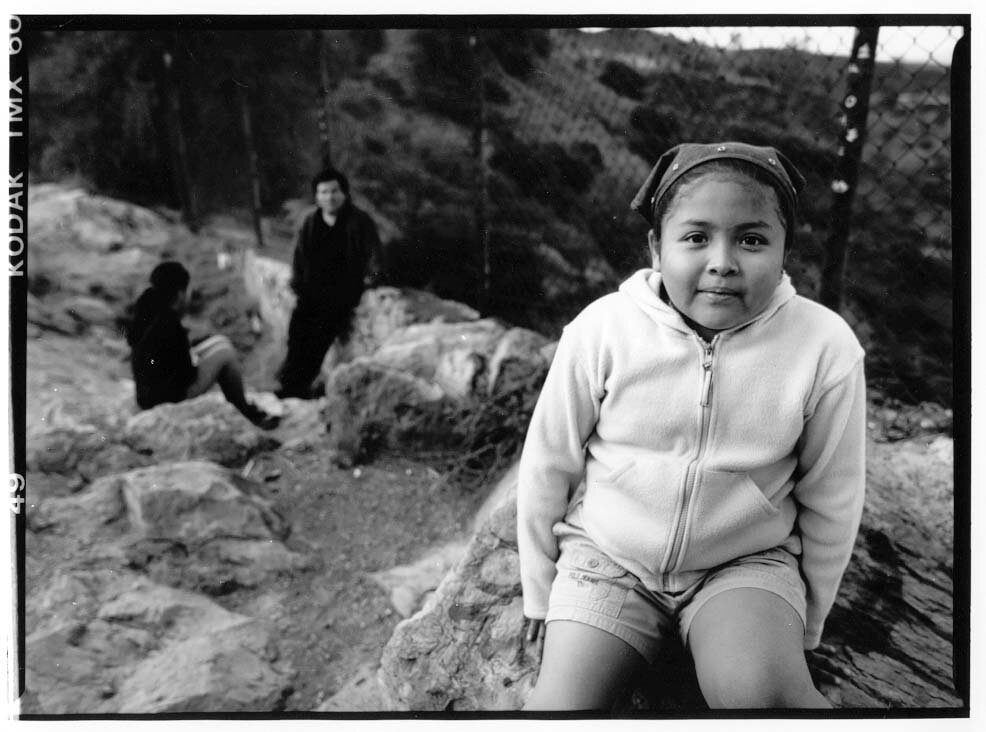

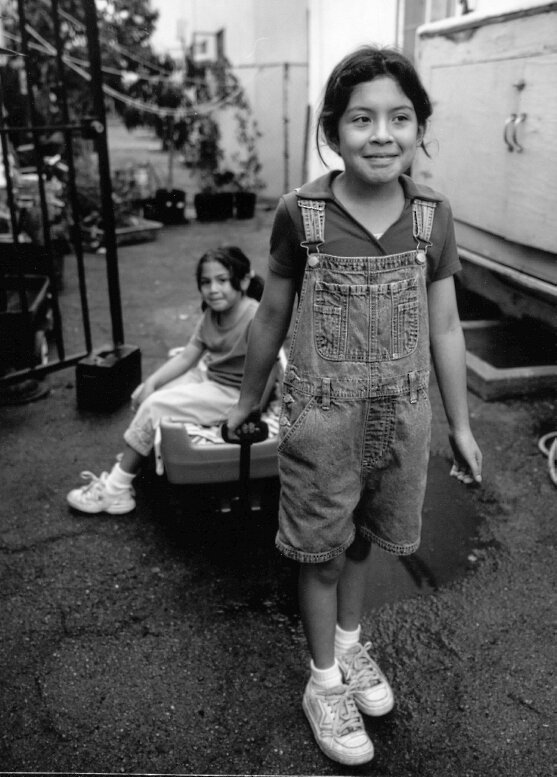

* Kimmy Limon, age 10

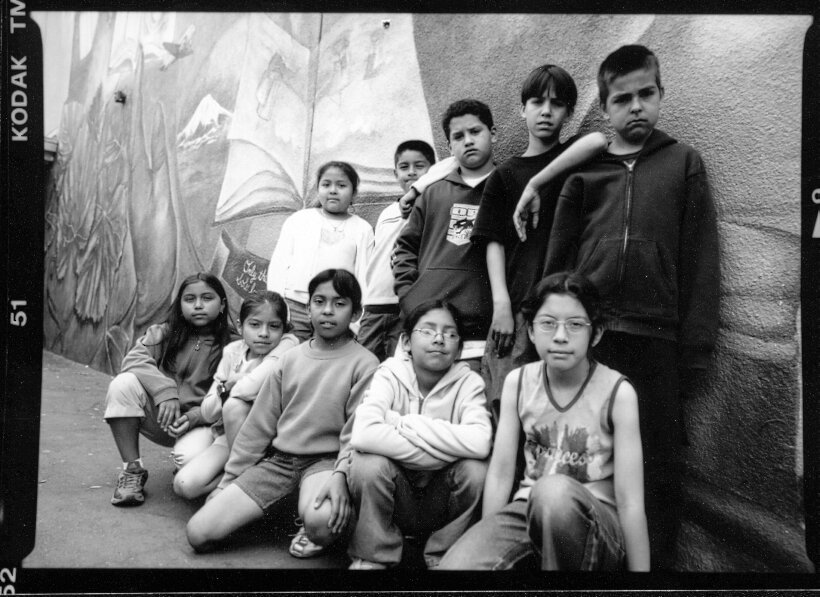

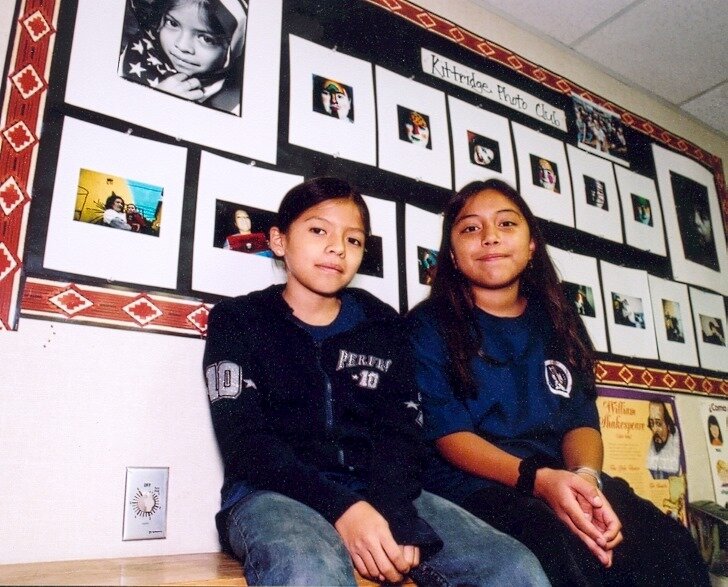

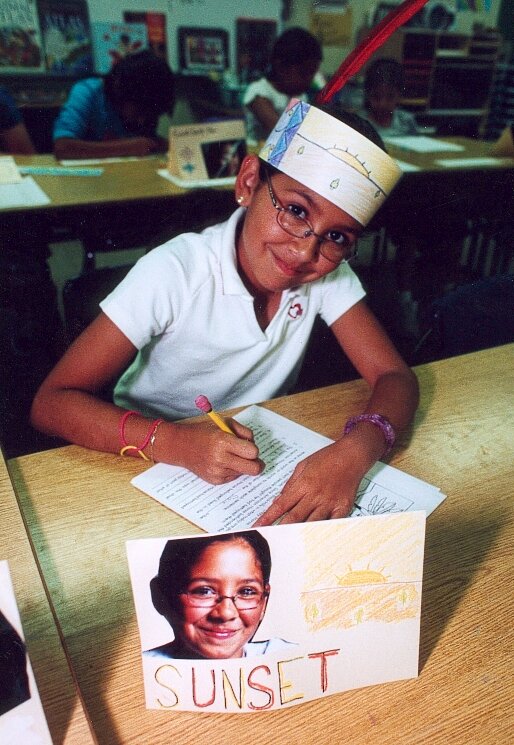

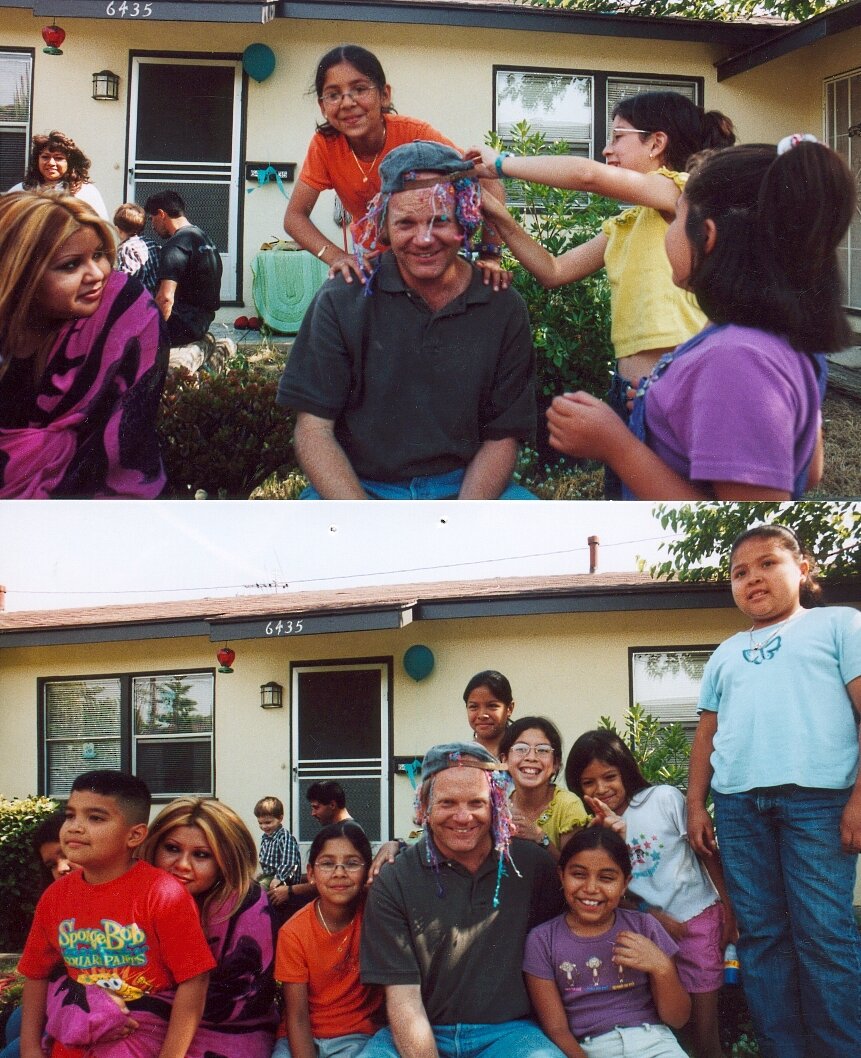

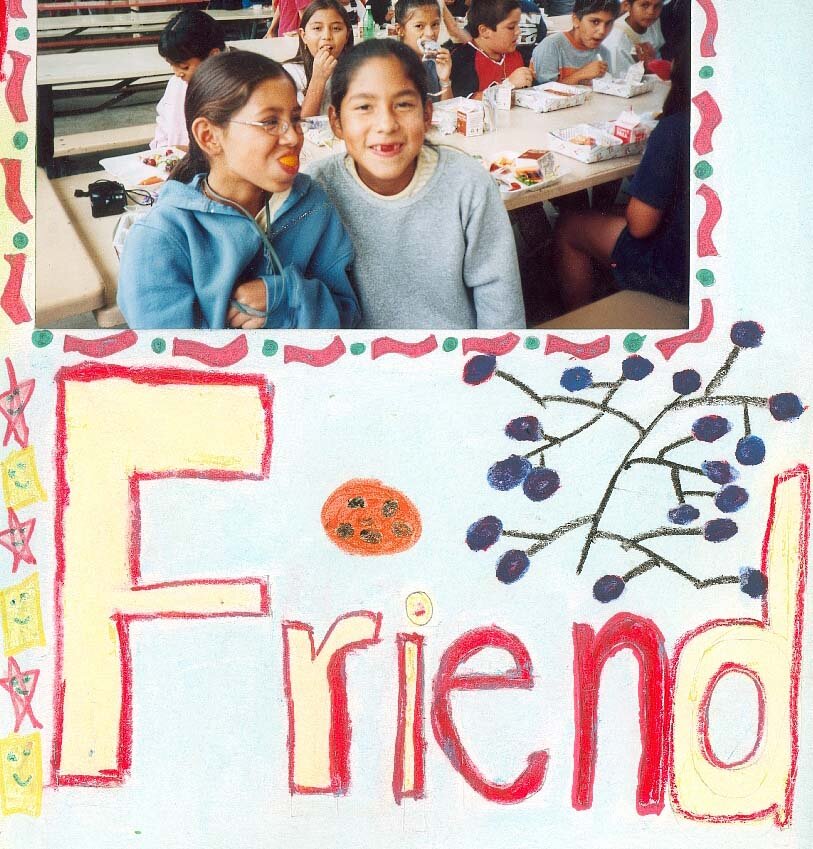

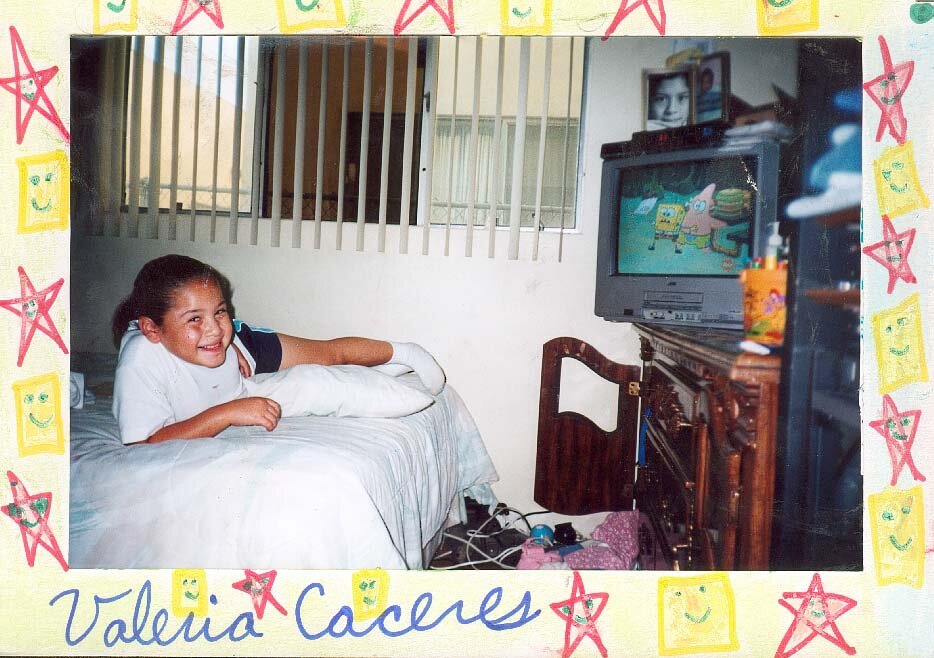

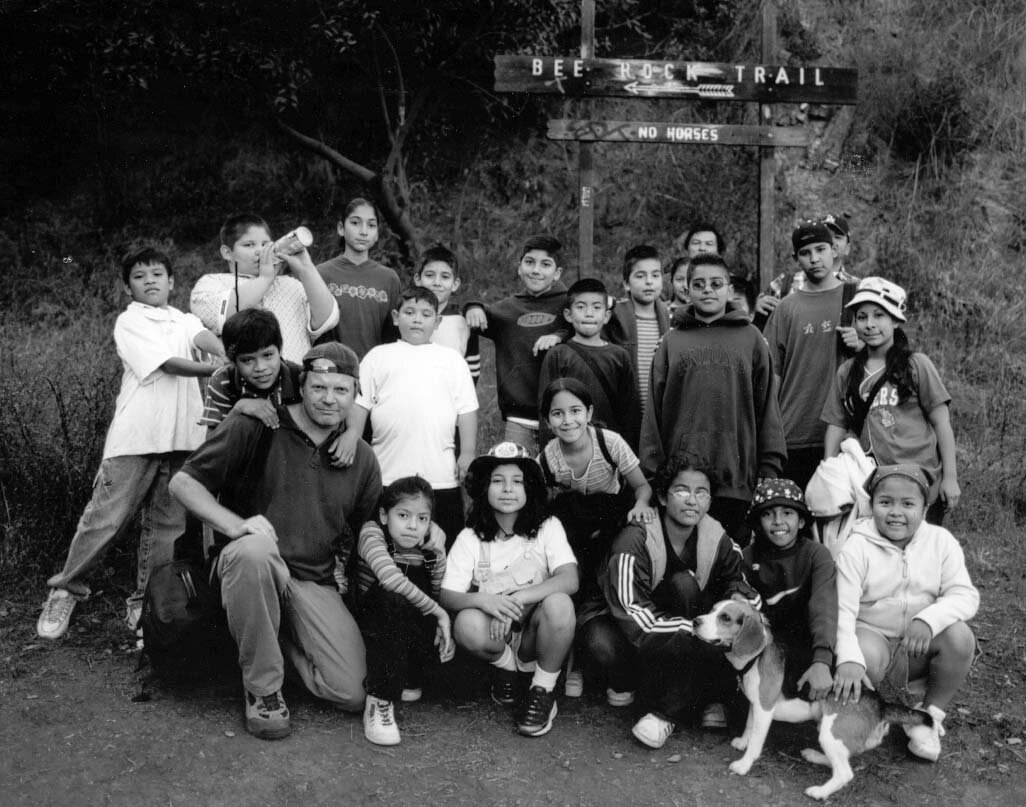

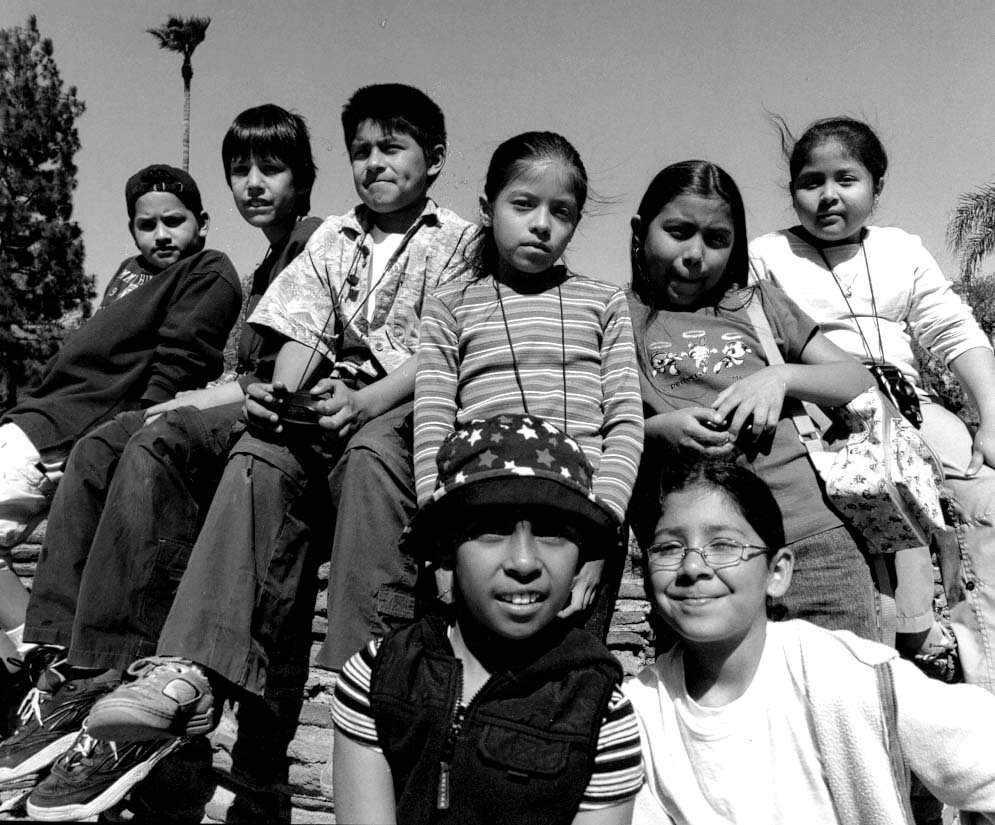

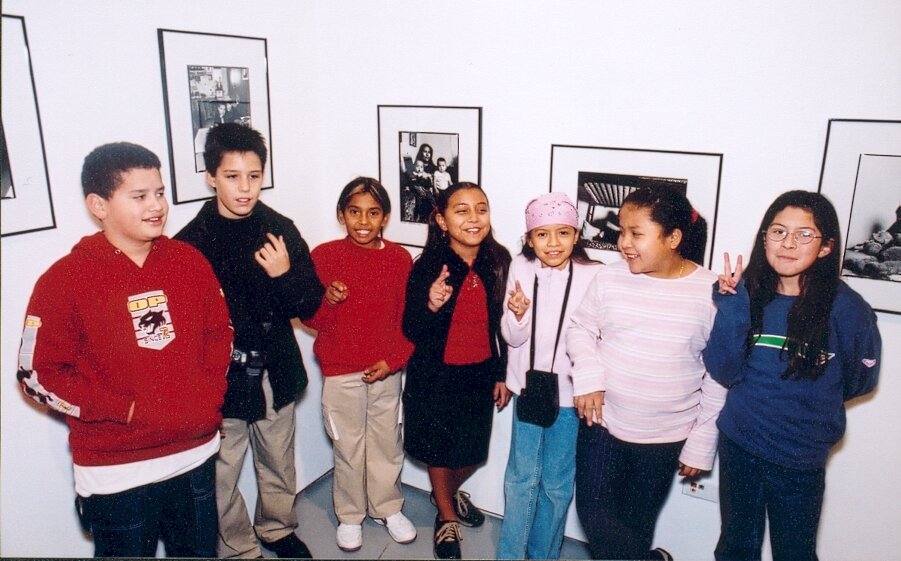

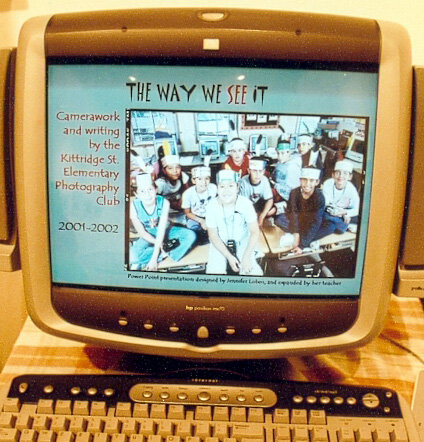

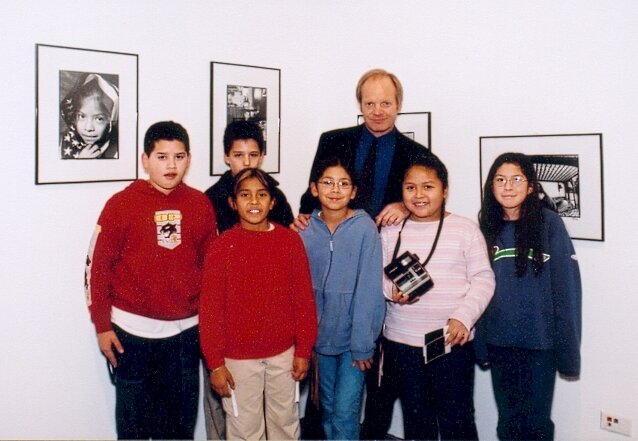

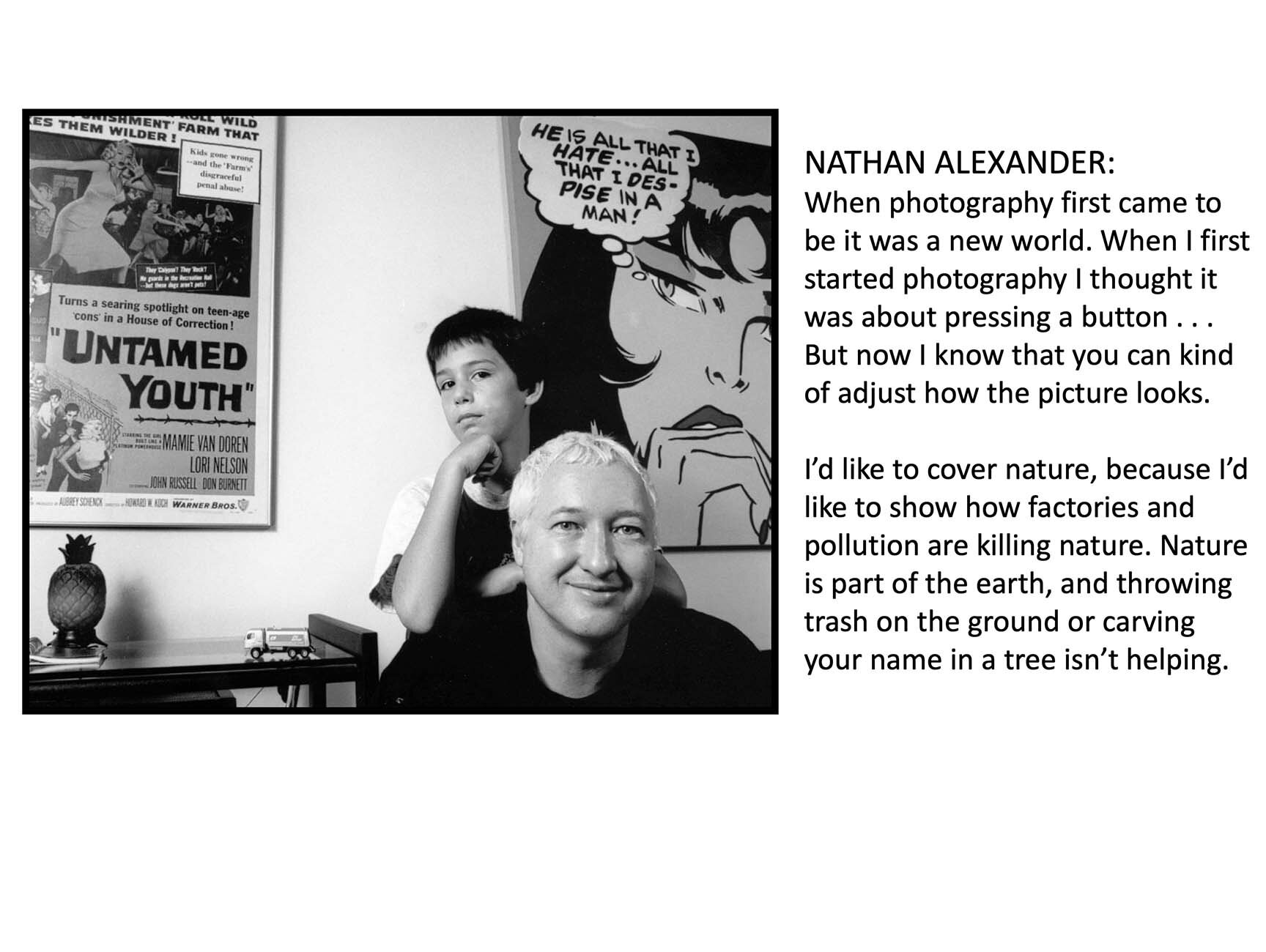

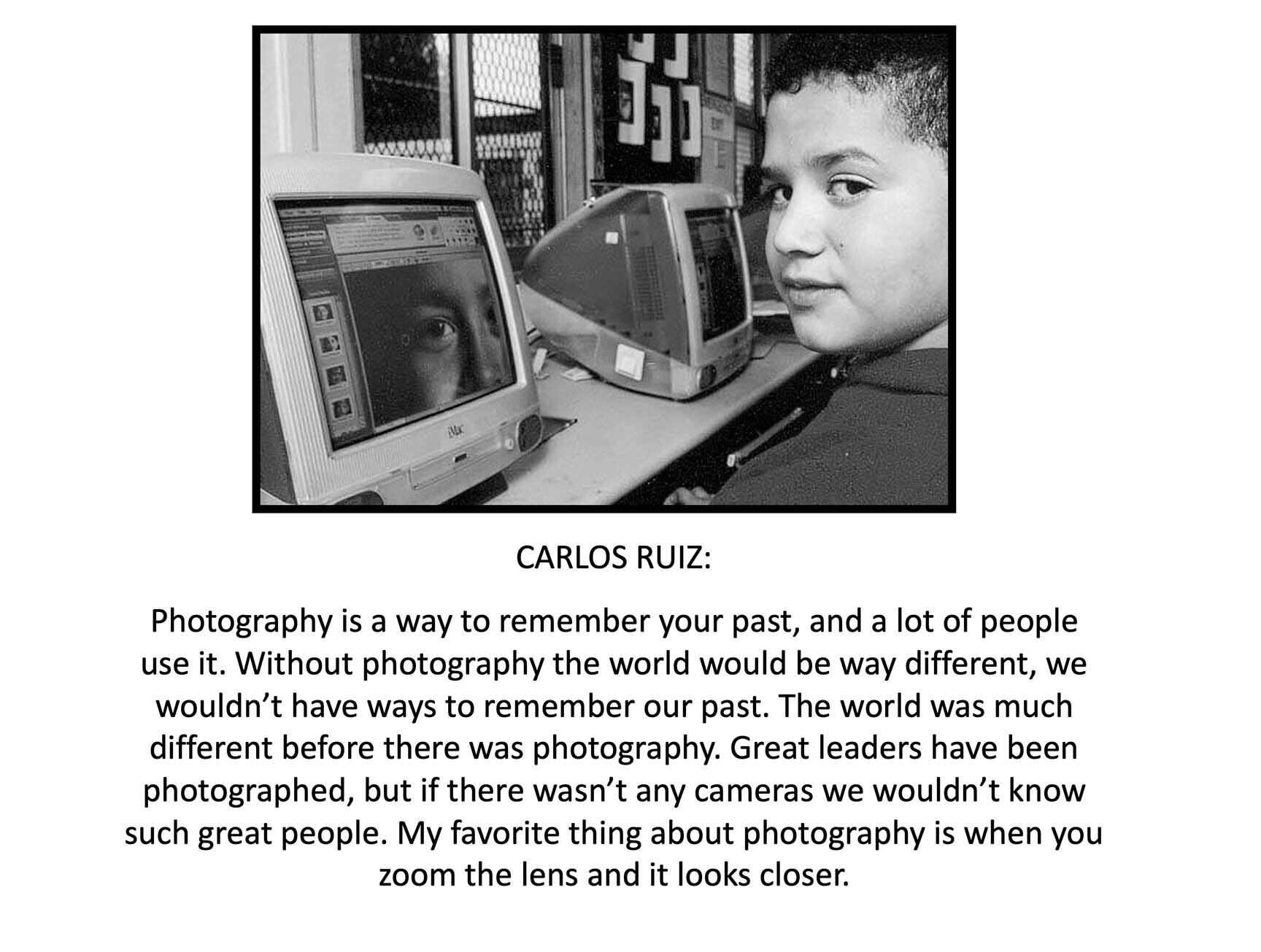

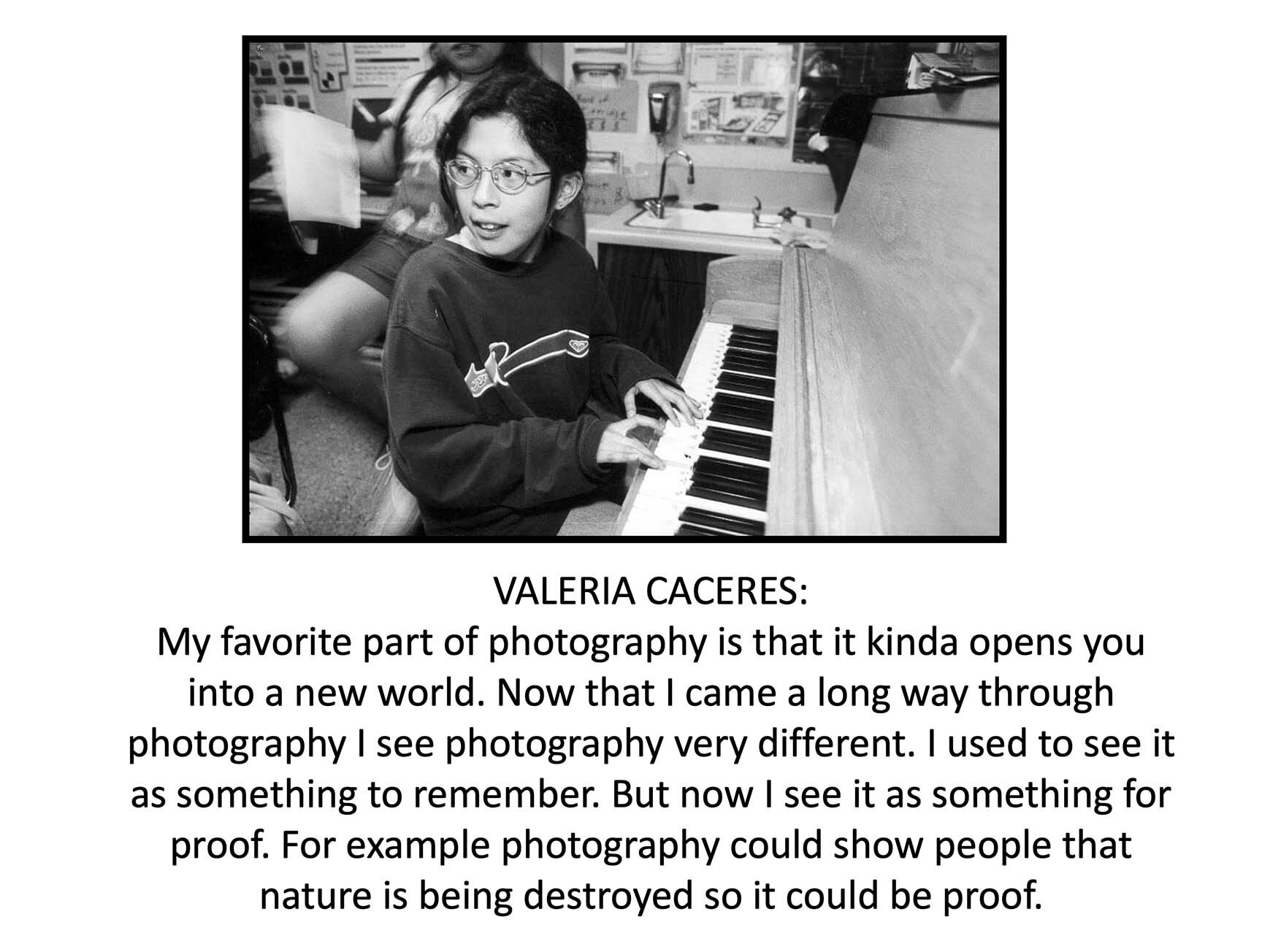

The Kittridge St. Elementary Photography Club, 2001. Front row (left to right): Eva Sanchez, Kimmy Limon, Grecia Vasquez, Karla Vega, Valeria Caceres. Back row: Jennifer Lobos, Bryan Merino, Carlos Ruiz, Nathan Alexander, Jesus Losoya.

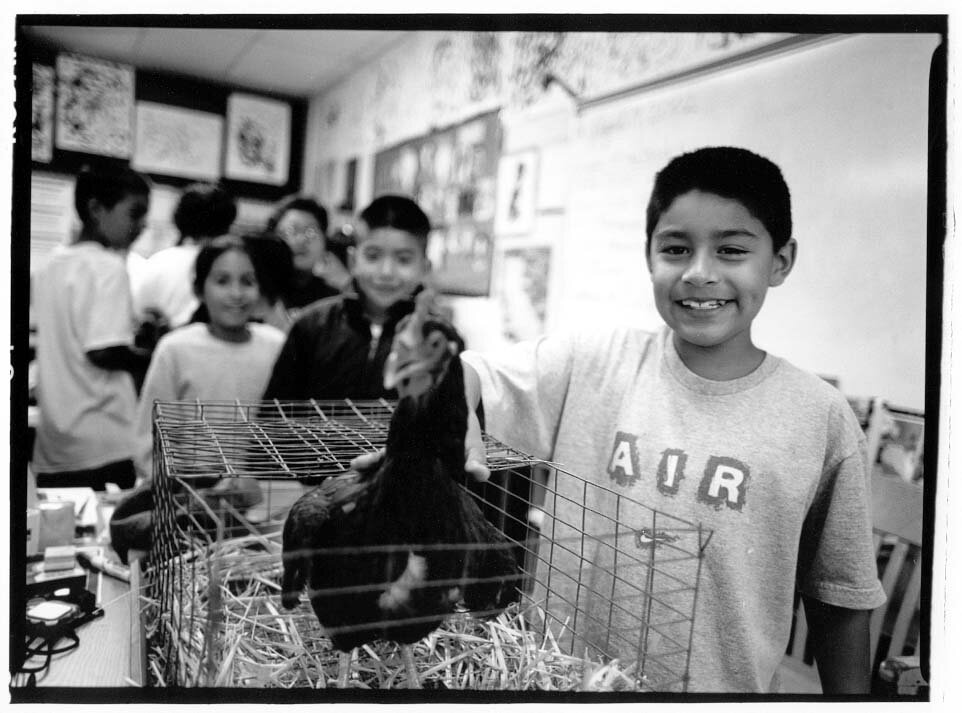

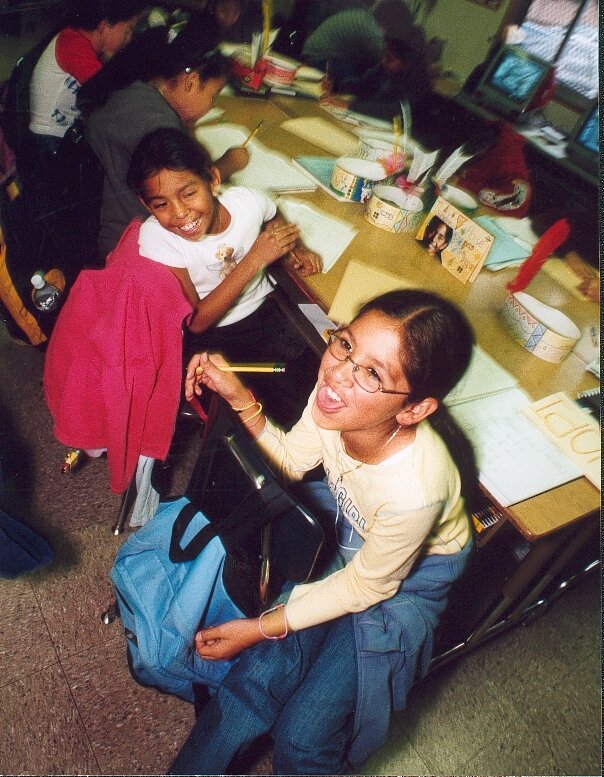

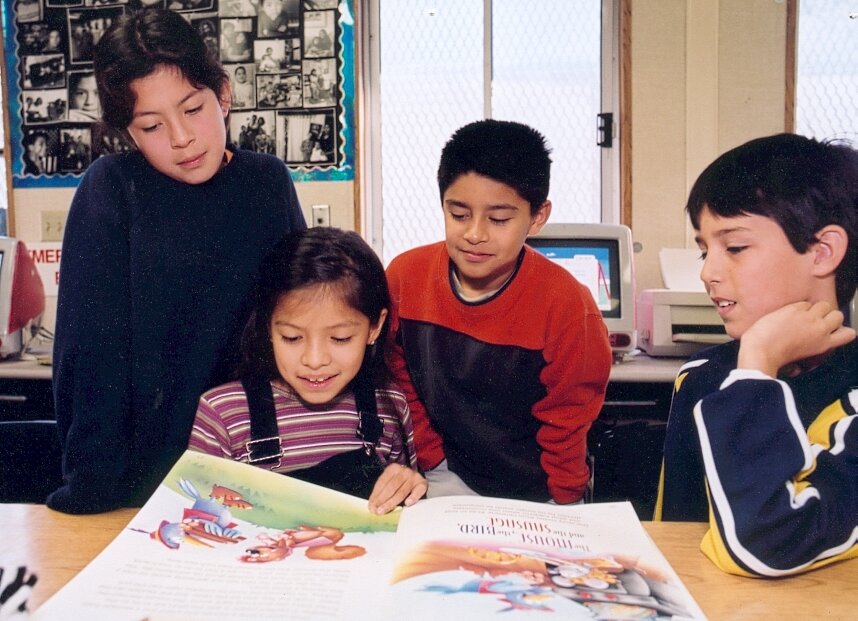

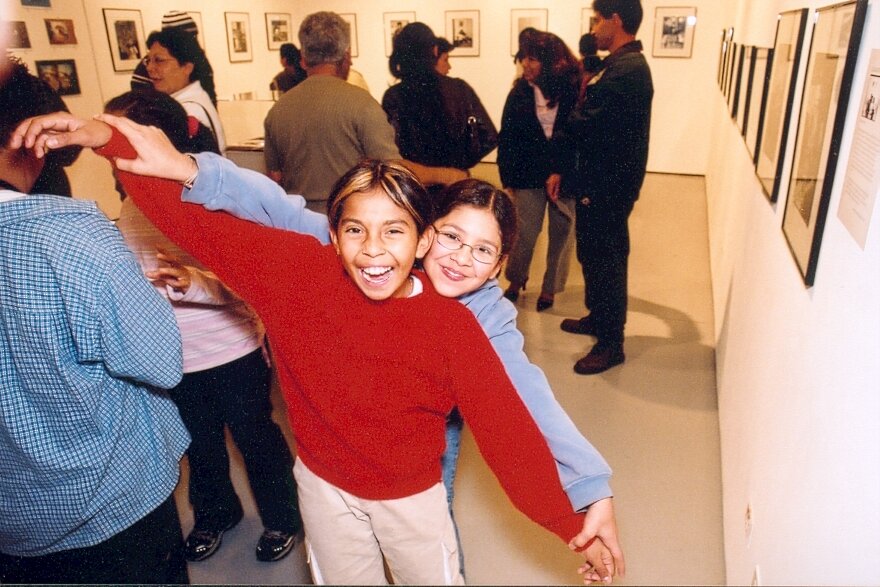

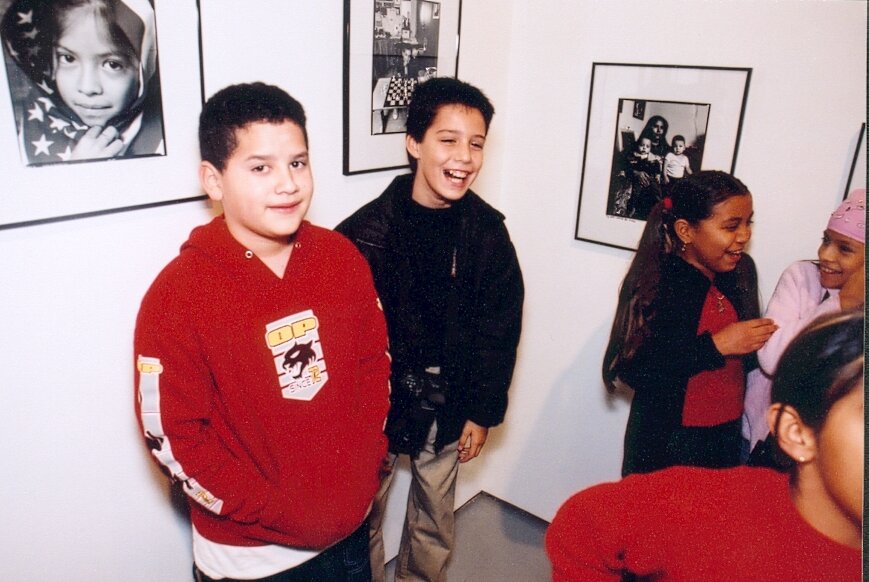

When creating a photography project for elementary school-aged children, there is always the risk that the material, if presented in too casual a manner, will be embraced lightly, as some sort of extracurricular, optional activity. This is not to blame the children of our public schools, who have been conditioned to expect anything associated with “art” as being undemanding, and essentially one-dimensional. While I have no qualms about creating activities that are “fun and easy,” I chose to use the idea of a “photography club” to fulfill a district-mandated requirement to design a “differentiated curriculum” for my cluster of students classified as Gifted & Talented (GATE). At the time, I had only eight GATE students, but soon added two “non-gifted” students to the group. (Figure 15) As the project progressed, these two students would, through a combination of talent, enthusiasm and effort, become indistinguishable from the GATE students. Having taught classes with gifted clusters for seven years, it is my conclusion that all motivated students who feel they have a stake in their education love being challenged with original, highly flexible activities. The difference I have seen exists mainly in the manner in which the “gifted or talented” child is able to comprehend abstract ideas, and synthesize knowledge into original ideas. Conversely, I have also seen numerous examples of “non-gifted” students who, in a given subject, have risen to the level of their counterparts, and in many cases outperformed them.

An extraordinarily bright and close group of kids made the project a pleasure to plan and implement…

Having always been a proponent of thematic teaching, and having had in the past implemented several “integrated” units for social studies and science, it was not difficult to adapt this method of curriculum design to the realm of photography. The initial curriculum of twenty activities thus included art analysis and criticism (photography history and technique), computer technology, a social studies component, essay and research report writing assignments, and vocabulary lists that introduced the students to the workings of the camera and elements of good photography.

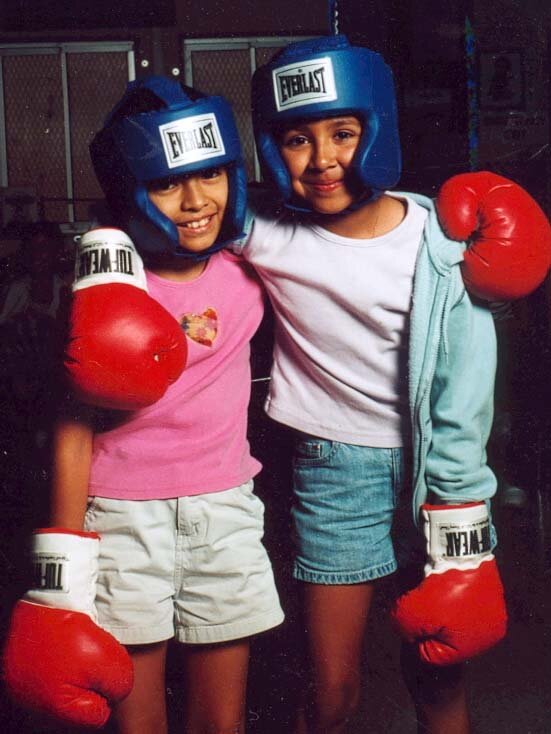

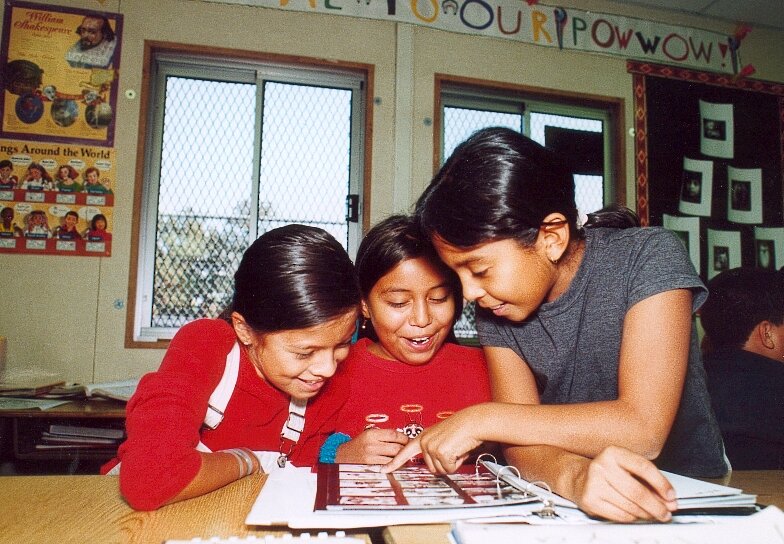

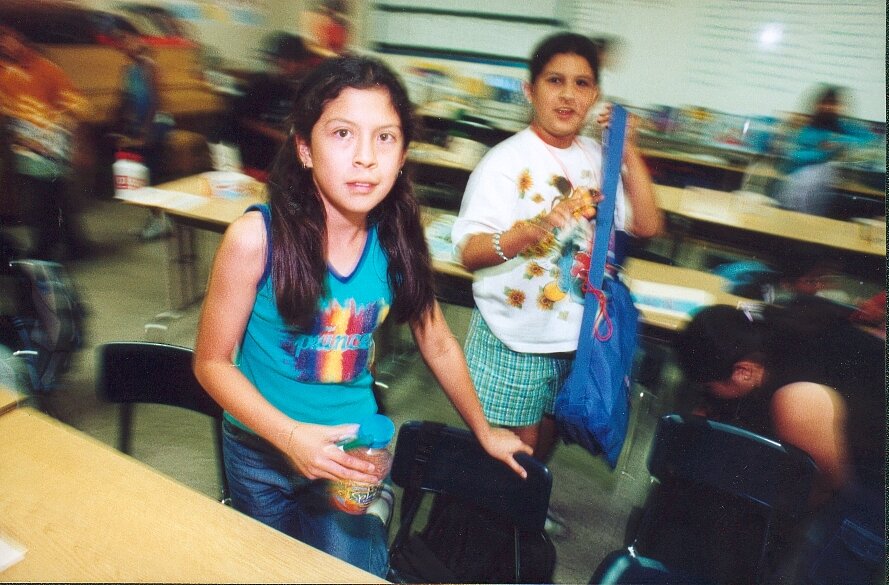

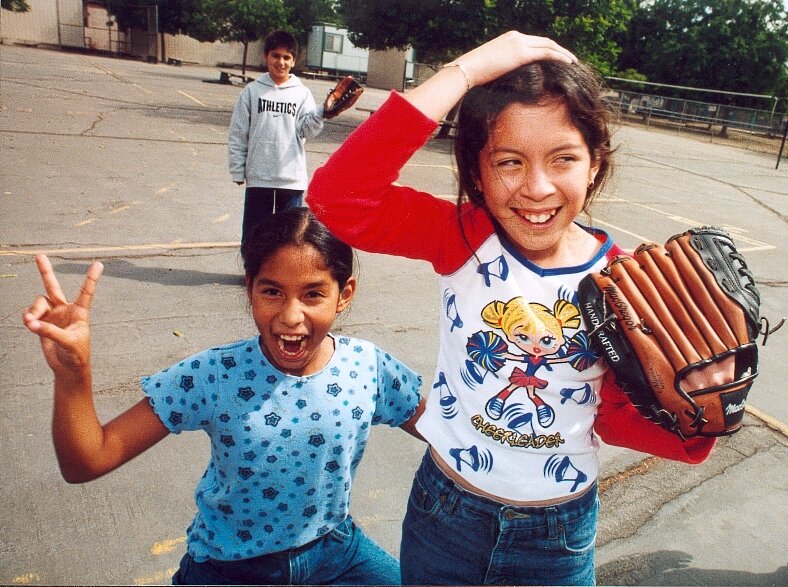

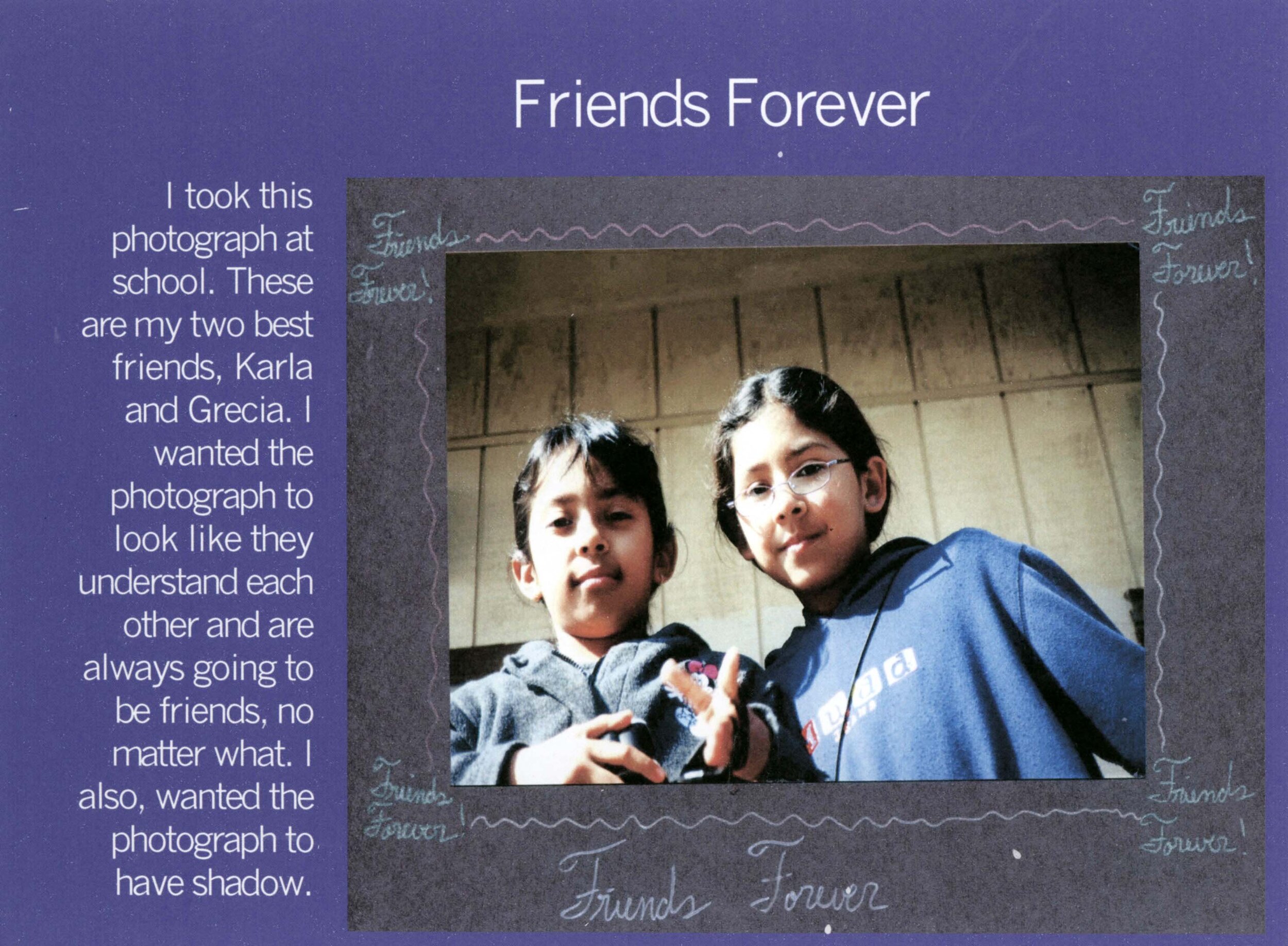

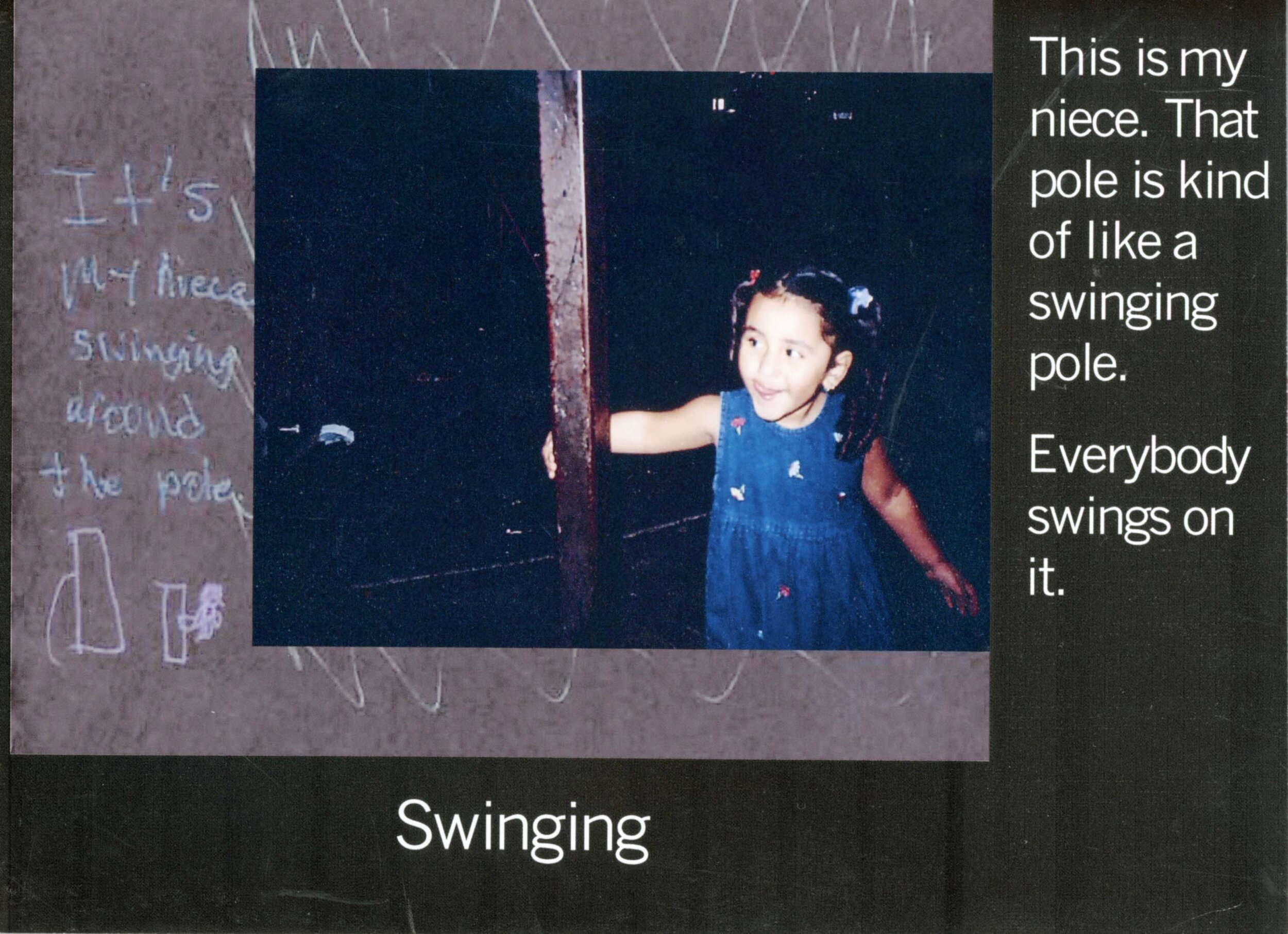

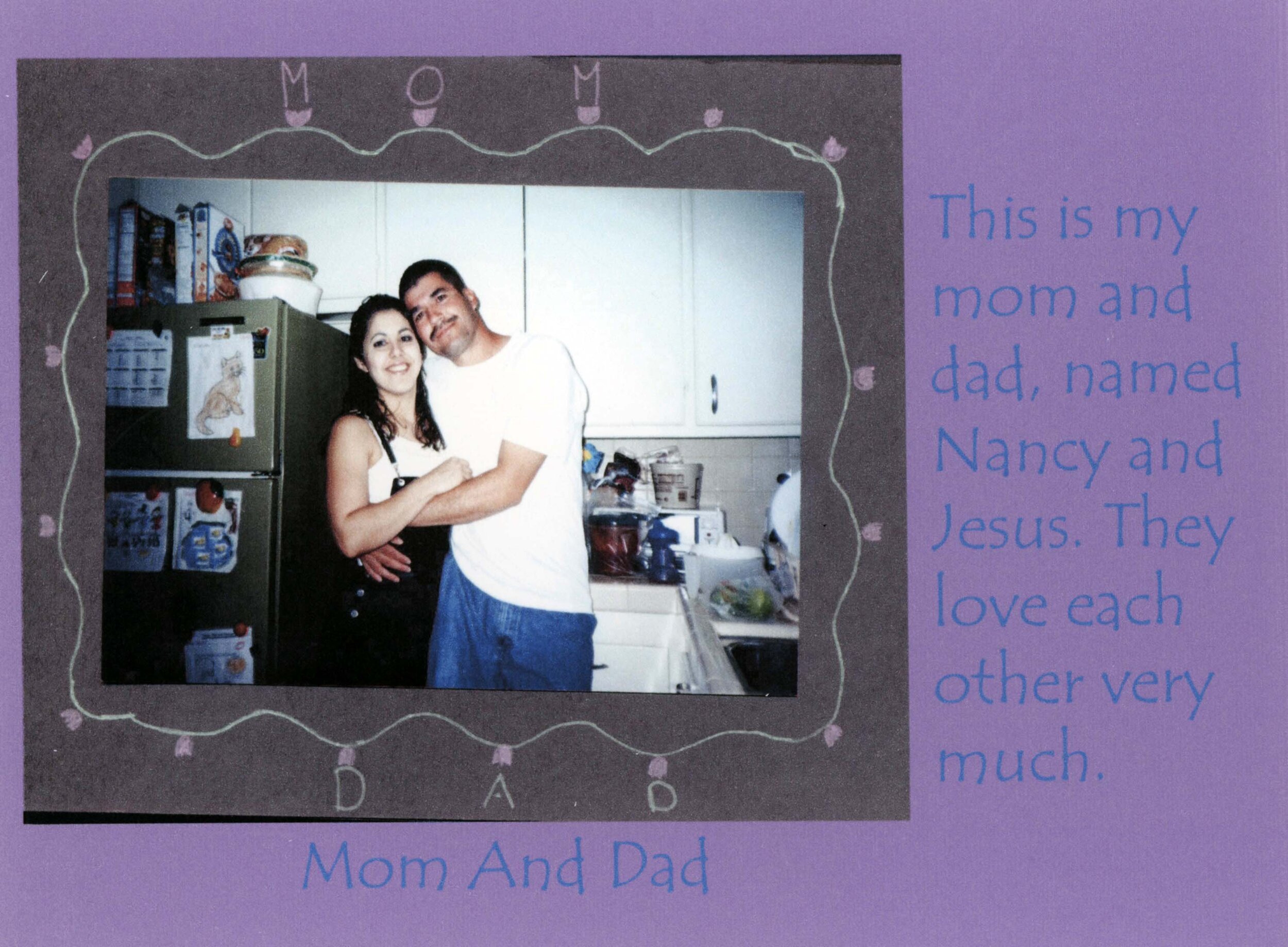

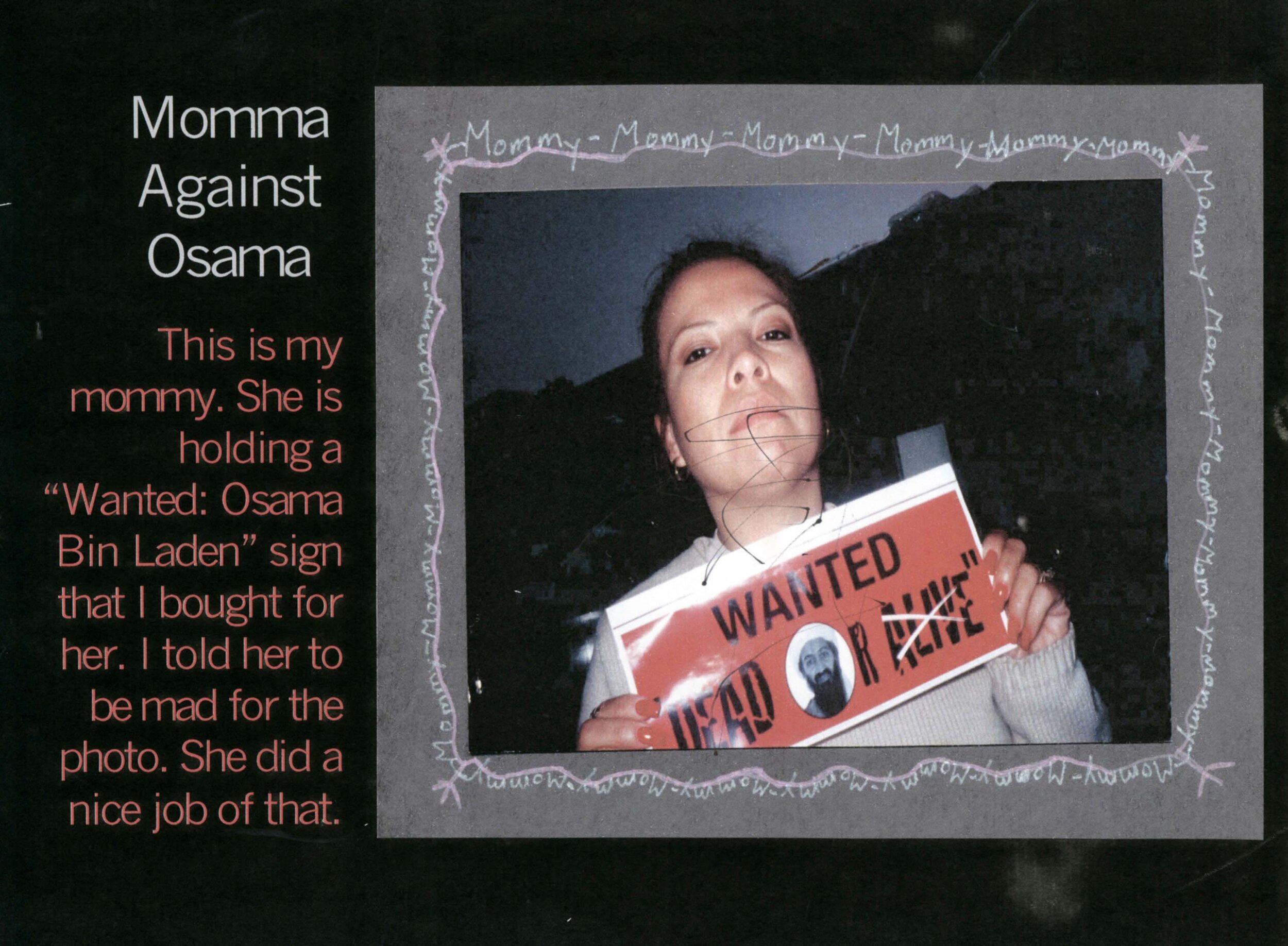

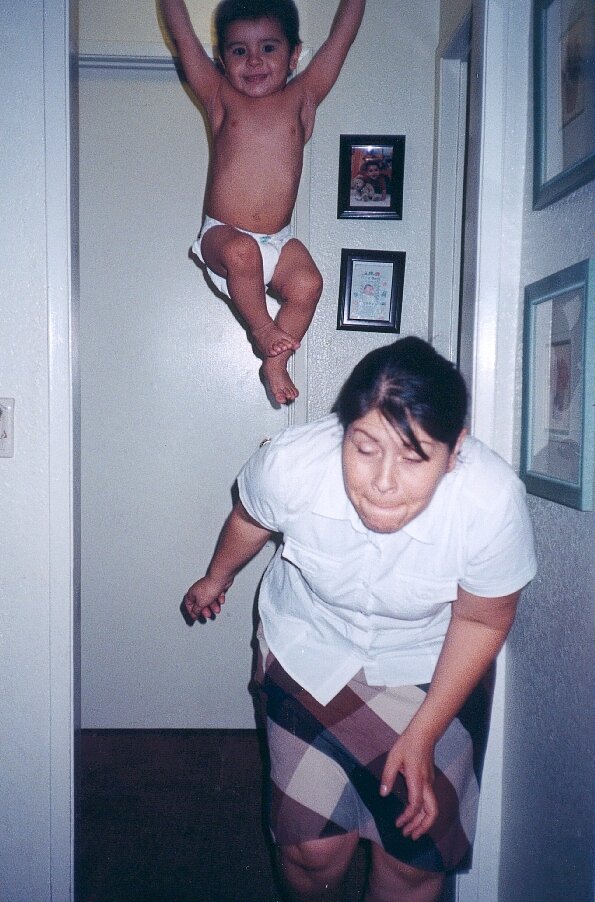

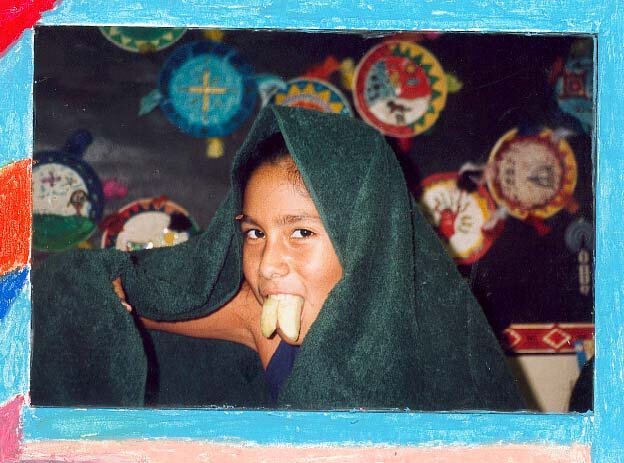

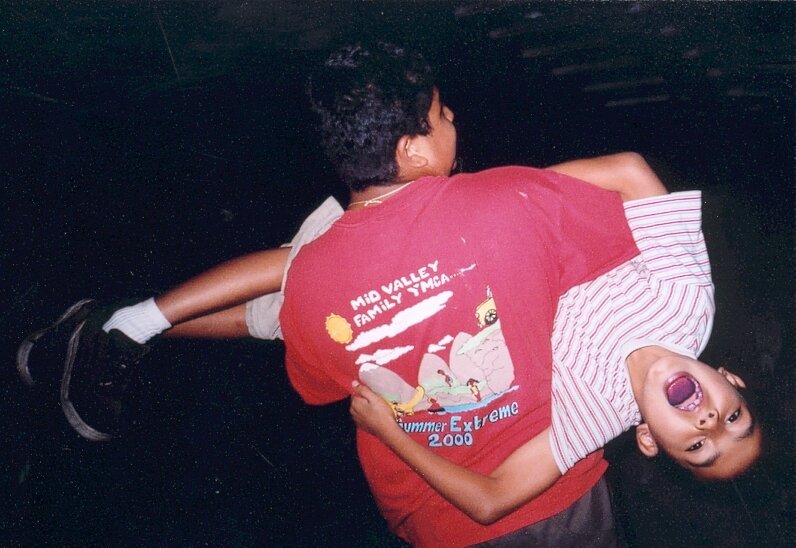

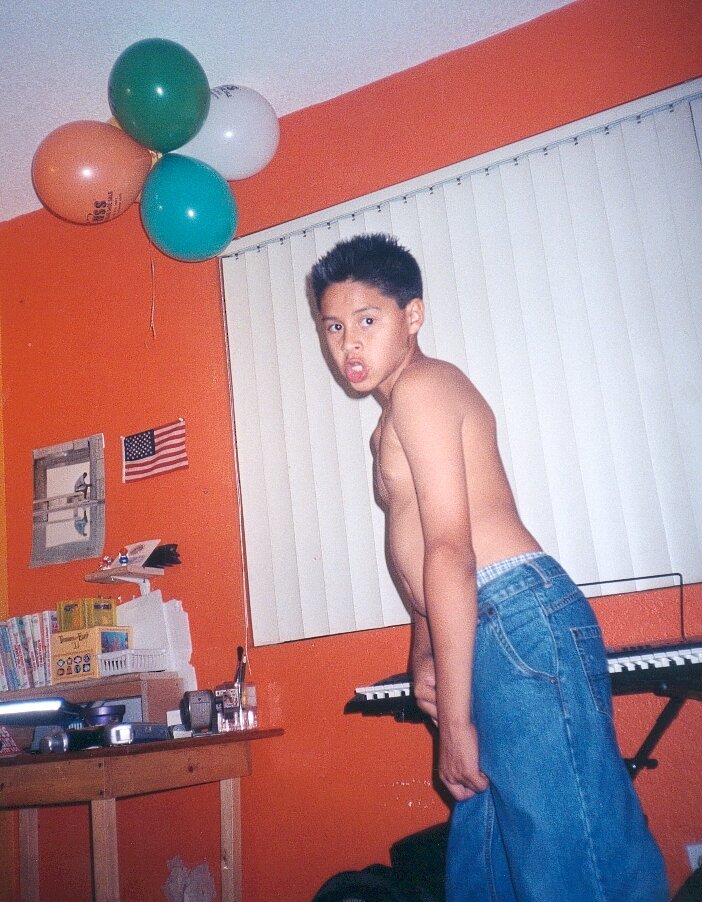

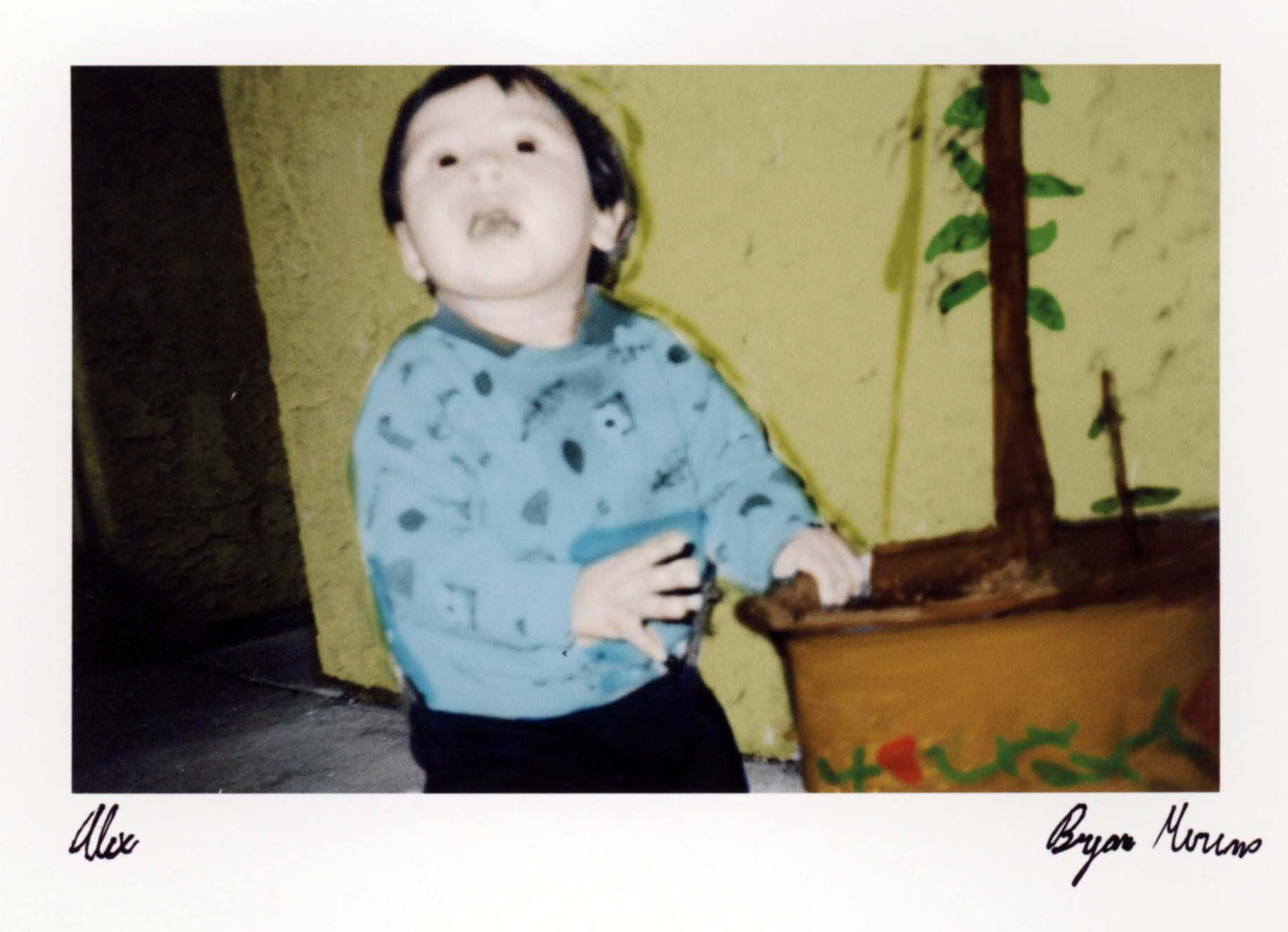

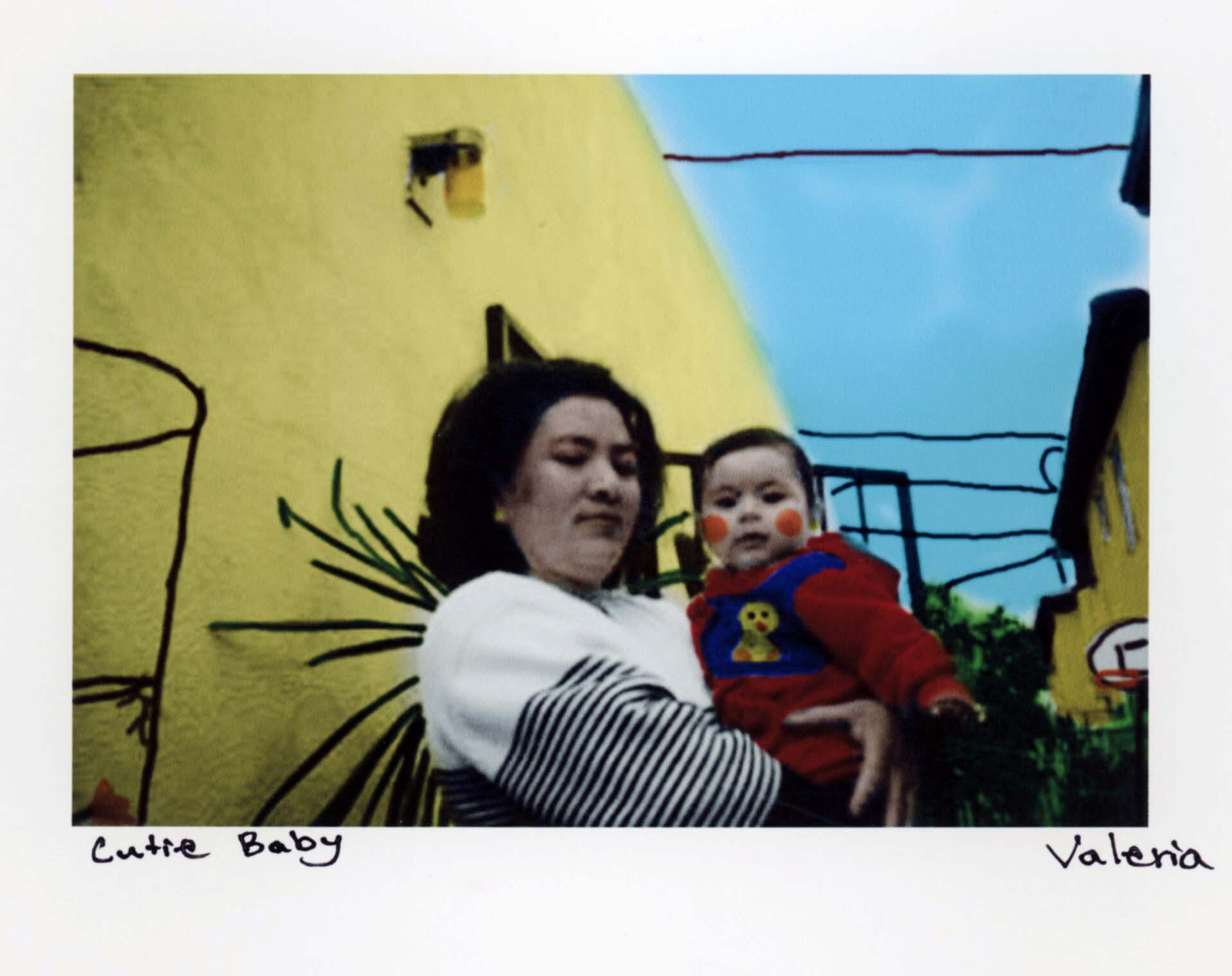

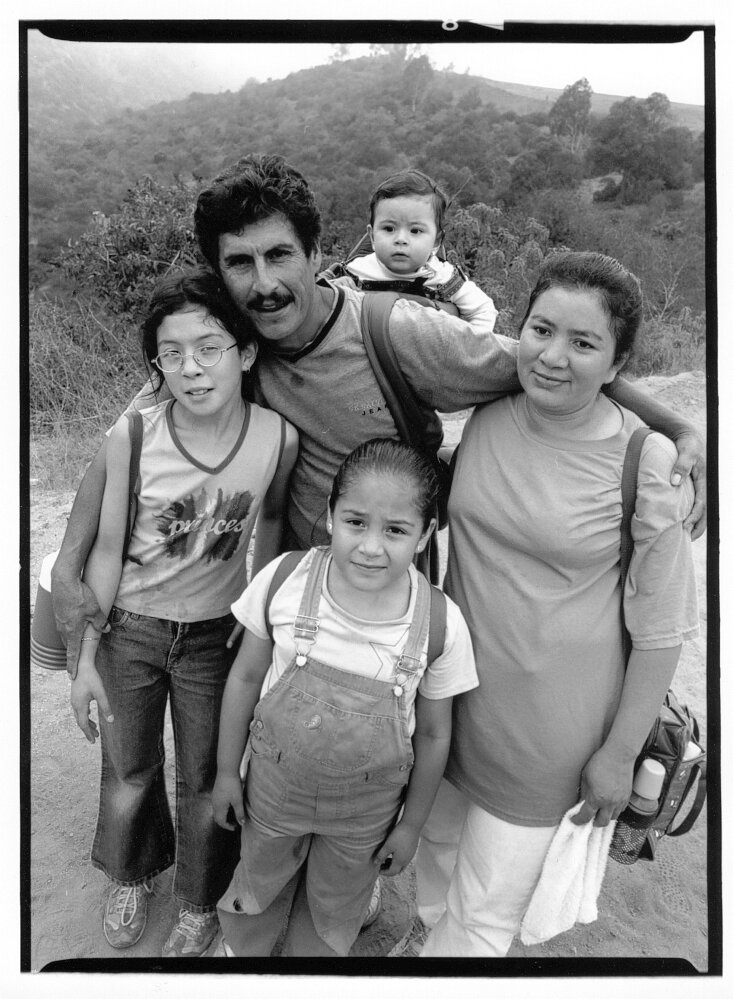

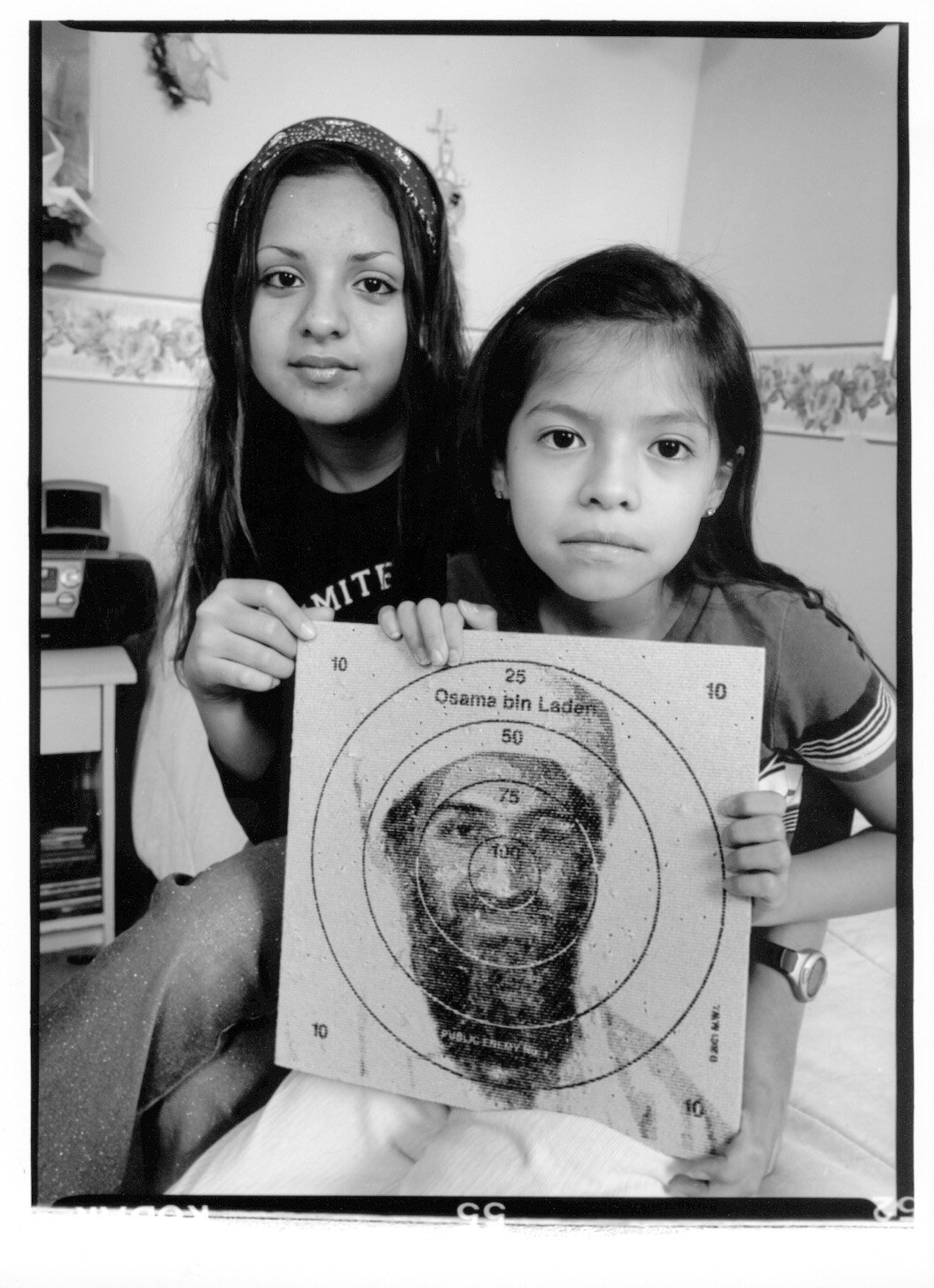

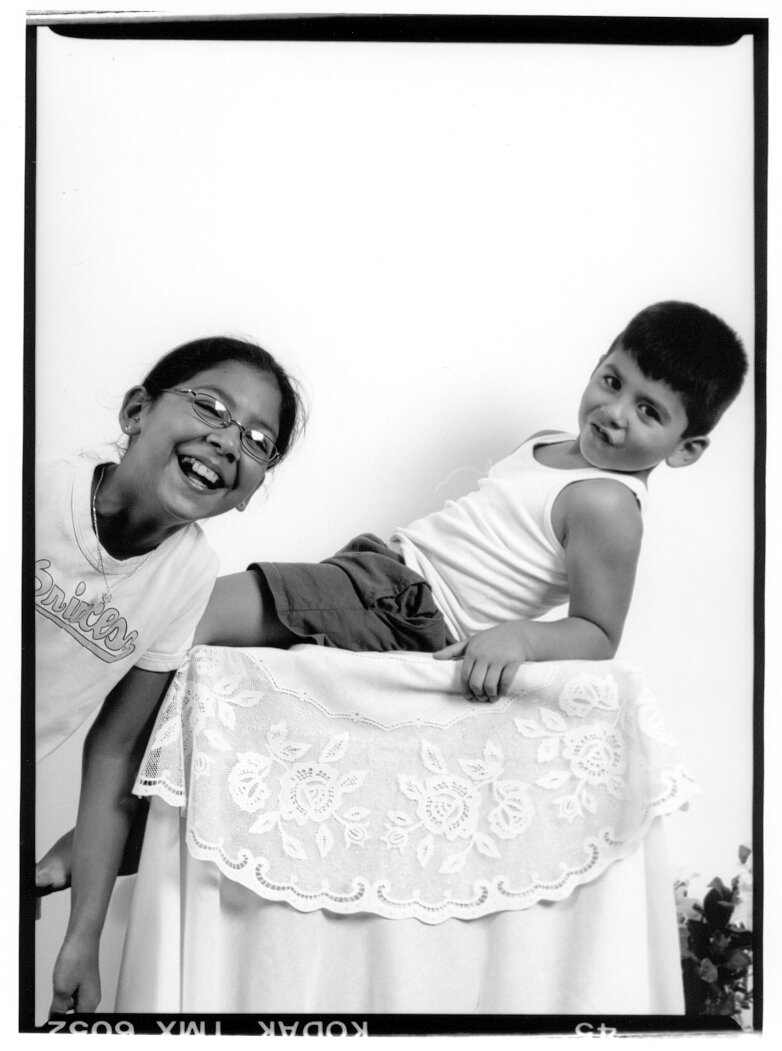

The main objective of the first few weeks was to get the students thinking about photography in very human terms. They were asked to think about the medium’s relevance, in terms of their own lives. We also talked a lot about the way photographs impact our popular culture, and the way they have depicted historical events. The students dutifully met their writing obligations, knowing that they would soon be given their cameras. By the third week, they were very anxious to actually start shooting their first assignment: a study of their personal worlds, incorporating “elements of good photography,” namely lighting, timing, composition, angle and proximity. Armed with their first rolls of Fuji ASA 200 film, and their inexpensive automatic Canon cameras (with built-in flash), the Photography Club was active. Much of what the students produced with those first rolls show family, friends and neighbors, often in candid, playful poses. (Figures 16-18) A small number of images, like Kimmy Limon’s Momma Against Osama, presented a more serious, even political view of the world. (Fig. 19) Generally, it could be said that the children were very instinctive in their use of iconography in their photographs.

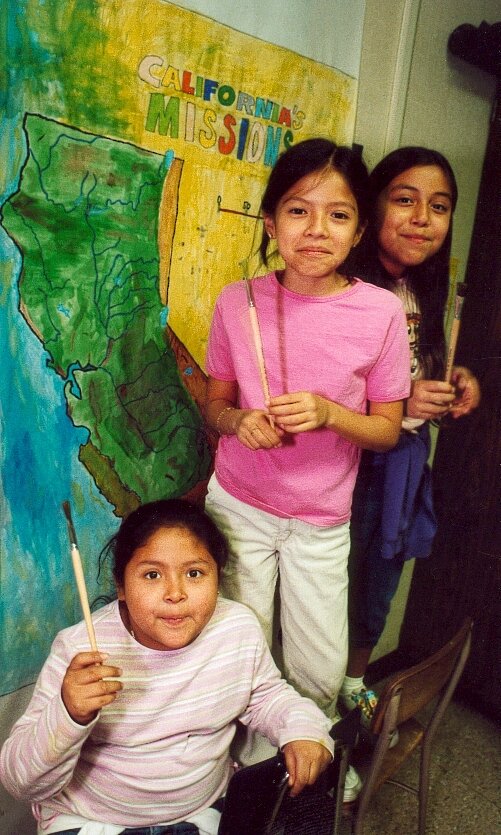

SOCIAL STUDIES COMPONENT

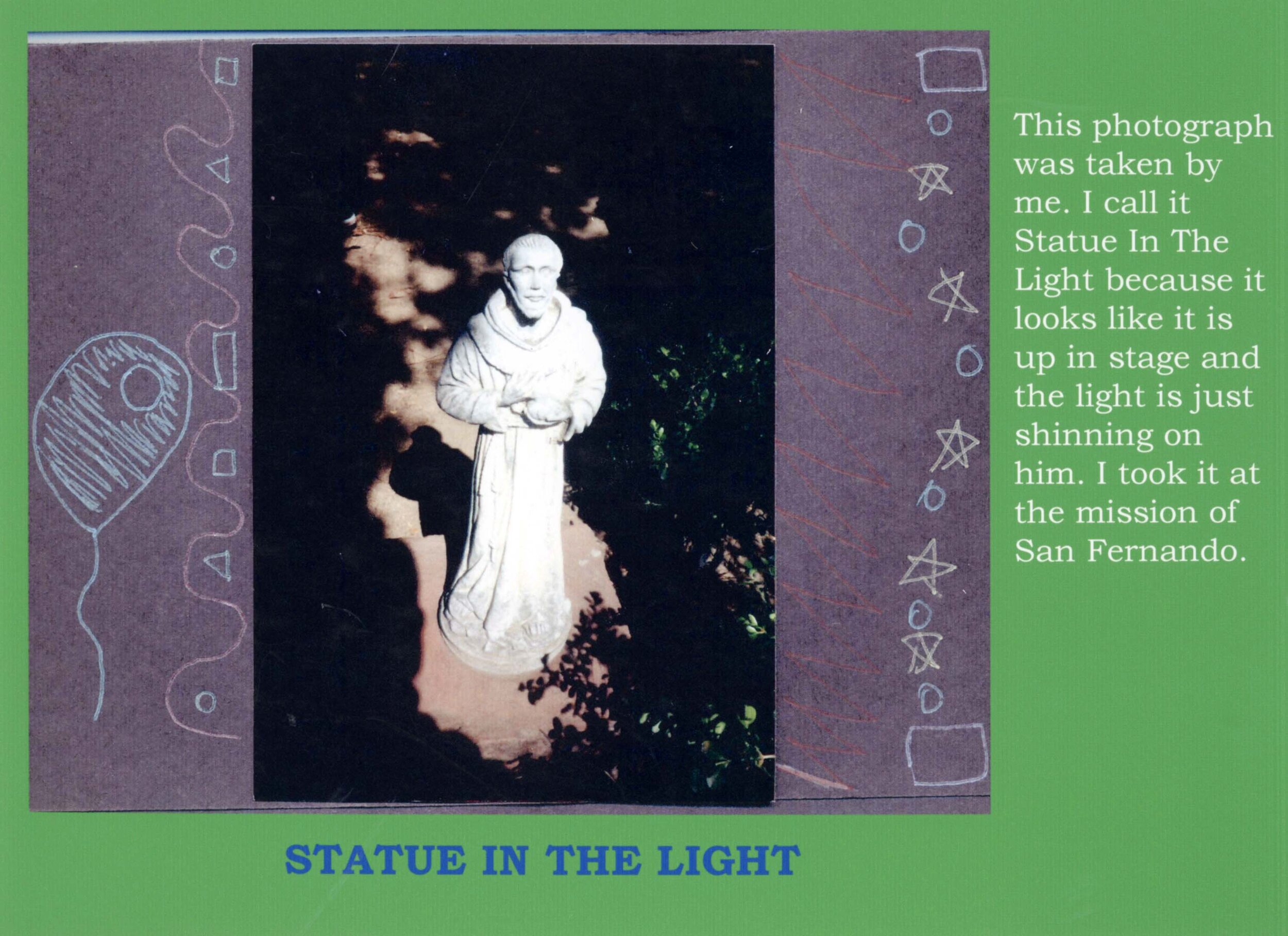

Students in my classes — and their parents -- are enthusiastic about our frequent weekend field trips, usually mountain hikes or visits to museums. The history of the Spanish Missions in California is a key feature of the fourth-grade social studies curriculum, and since our school community is only five miles from the San Fernando Mission, a trip to this historic site became the young photographers’ second assignment. As expected, the students’ use of the camera to interpret the architecture, iconography and aura of the mission reflected a blend of reverence and playfulness.

THE WAY WE SEE IT GALLERY Research and thesis abstract can be found at this link

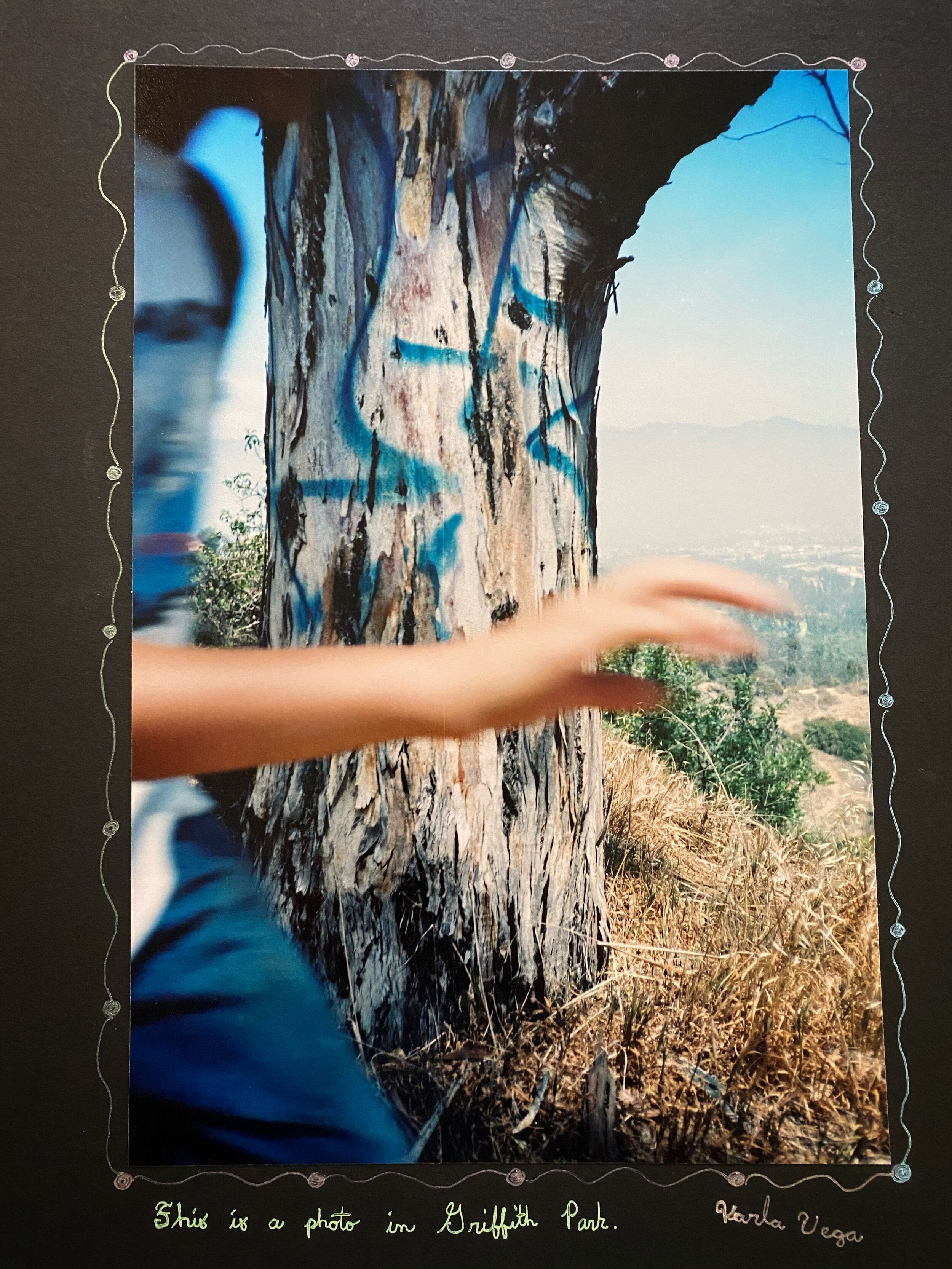

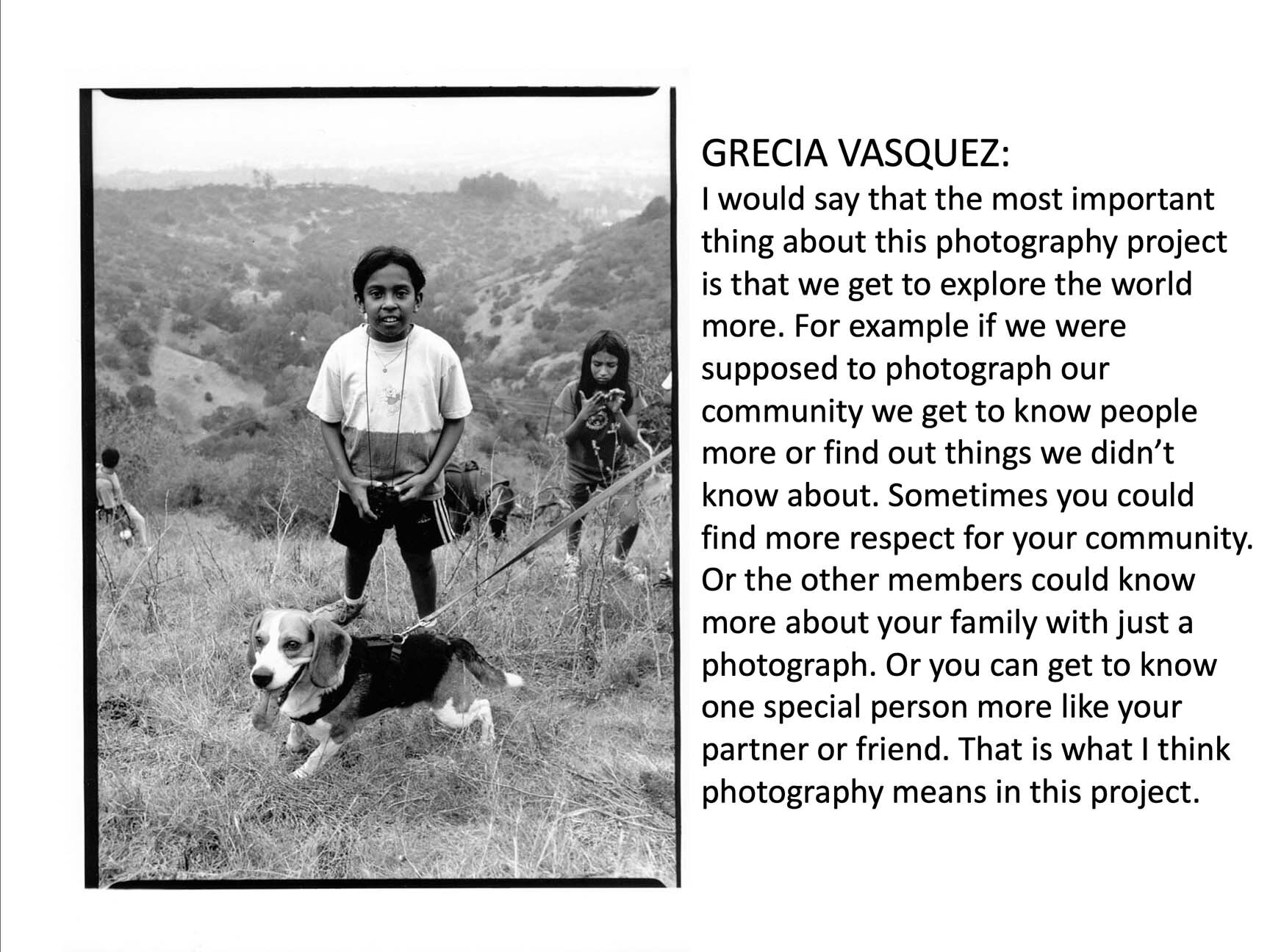

A month or two later, at the behest of the students, we took our cameras on a spontaneous “photo assignment,” into the hills of Griffith Park, the large, municipally owned park in the center of Los Angeles. Our goal was to document the graffiti that marred the natural beauty of many of the park’s trails. With the usual brigade of children and parents, we hiked for a few hours on our regular paths, and then to some other areas that had lots of graffiti, including the site of the original Los Angeles Zoo, where graffiti artists have used the abandoned cages and buildings as canvasses for their postmodern urban expression.

COLLABORATIONS: BRINGING THE CAMERA HOME

The camera itself, various articles attest, creates an environment of collaboration and cooperation, an attribute that is especially useful in bringing parents into the teaching process. As the cameras pass back and forth between school and home, the “walls of the school diminish and become permeable. Parents become active and interested . . .” (Nash 36)

“Photography integrates students’ lives inside and outside of school. Because the camera is an instrument associated with the . . . visual domain that they have known since birth, most students are able to use it as a vital bridge between school and society.” (37)

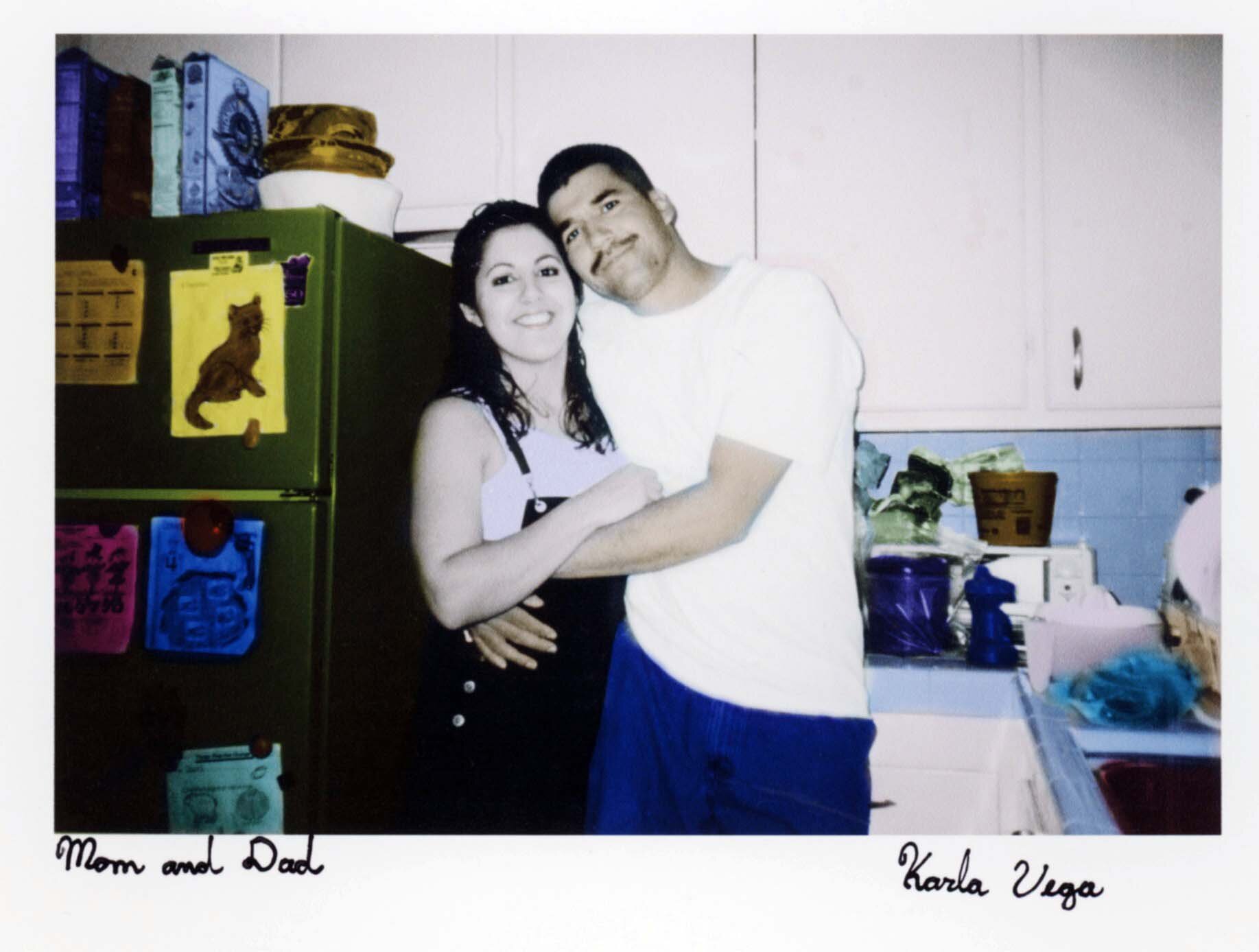

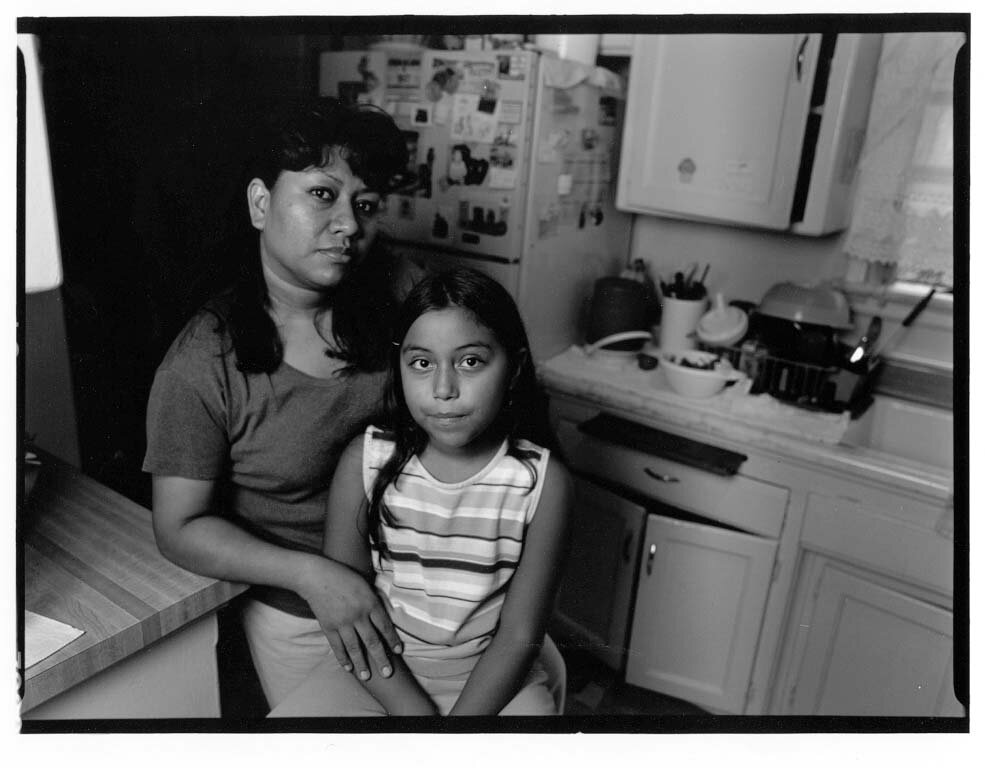

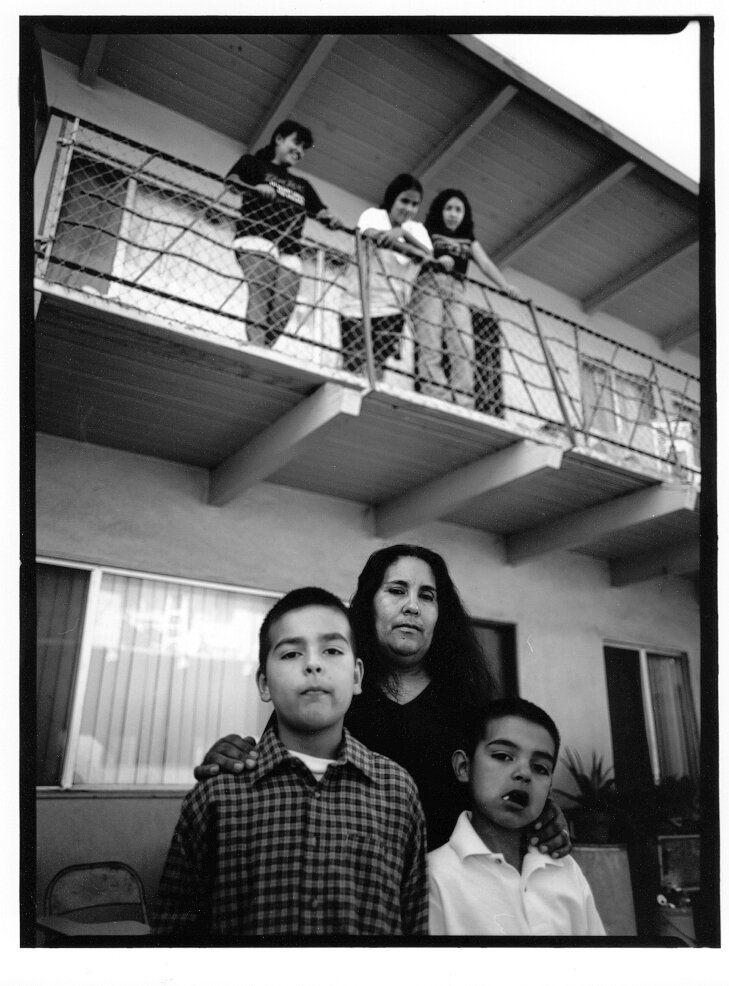

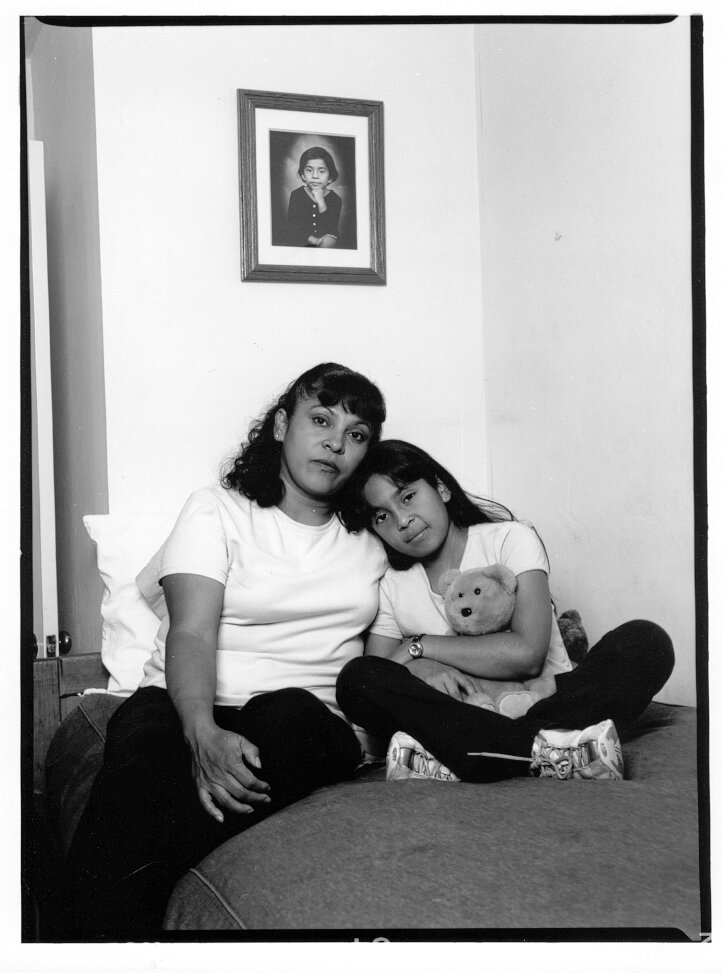

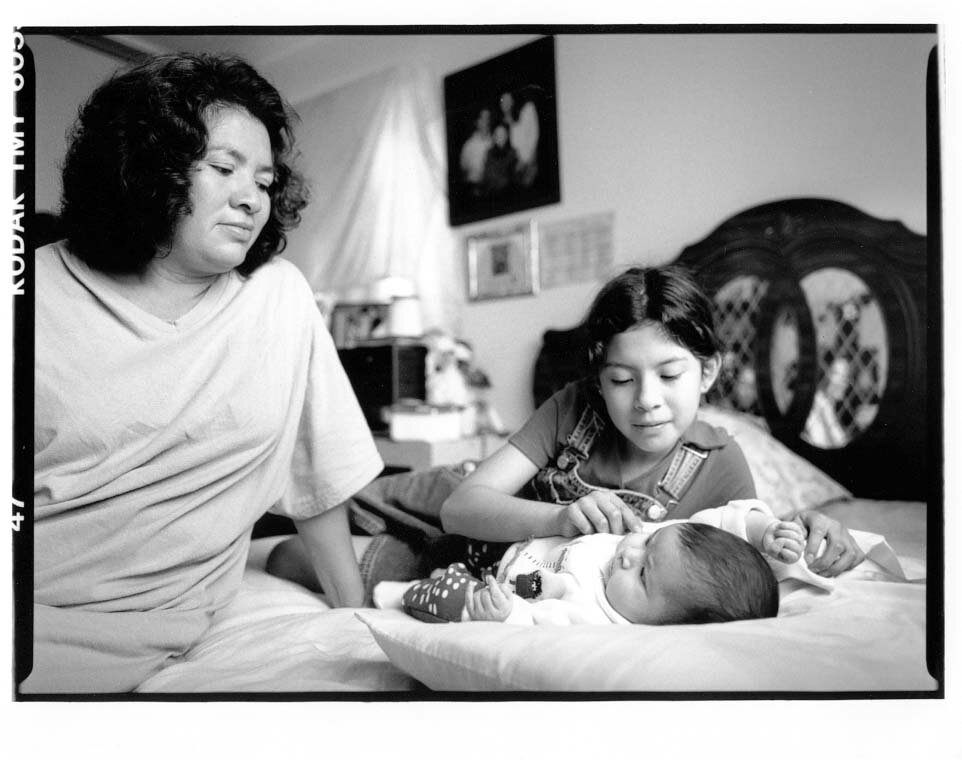

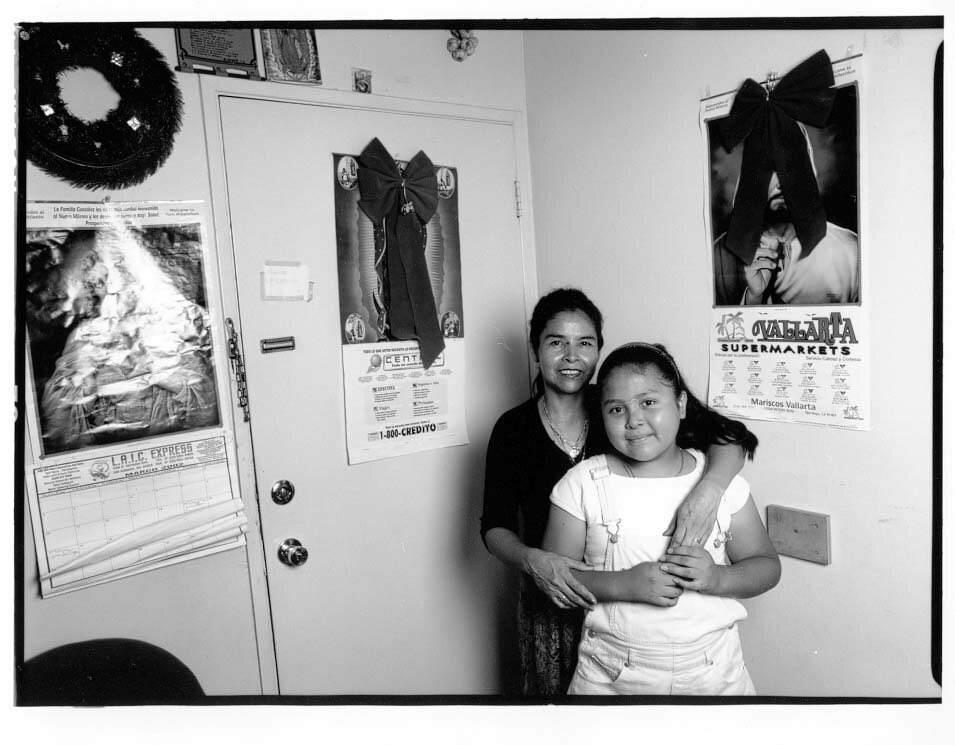

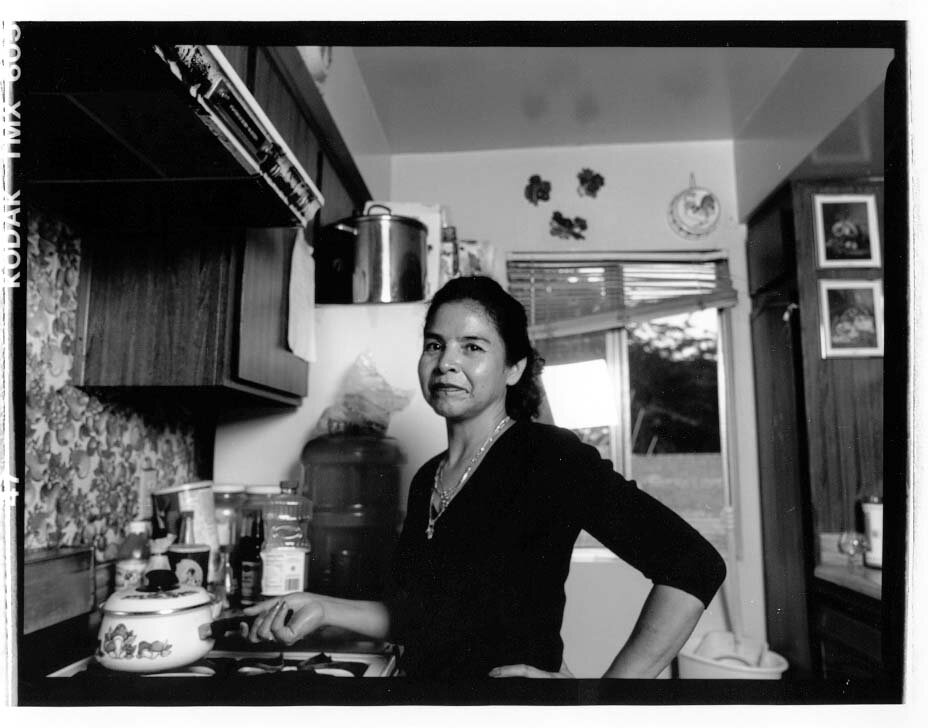

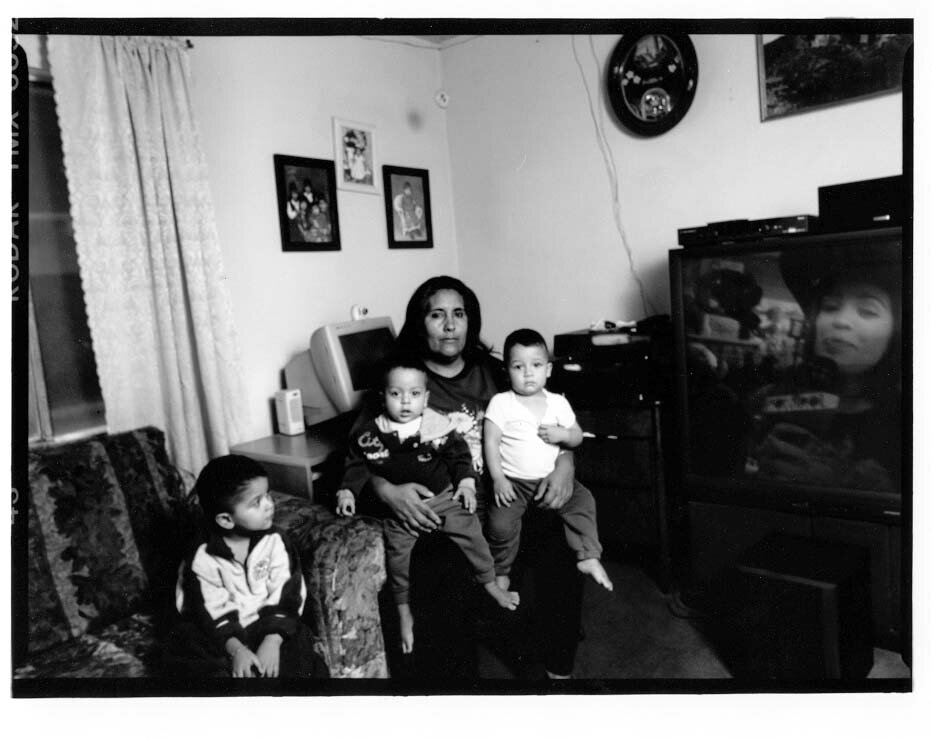

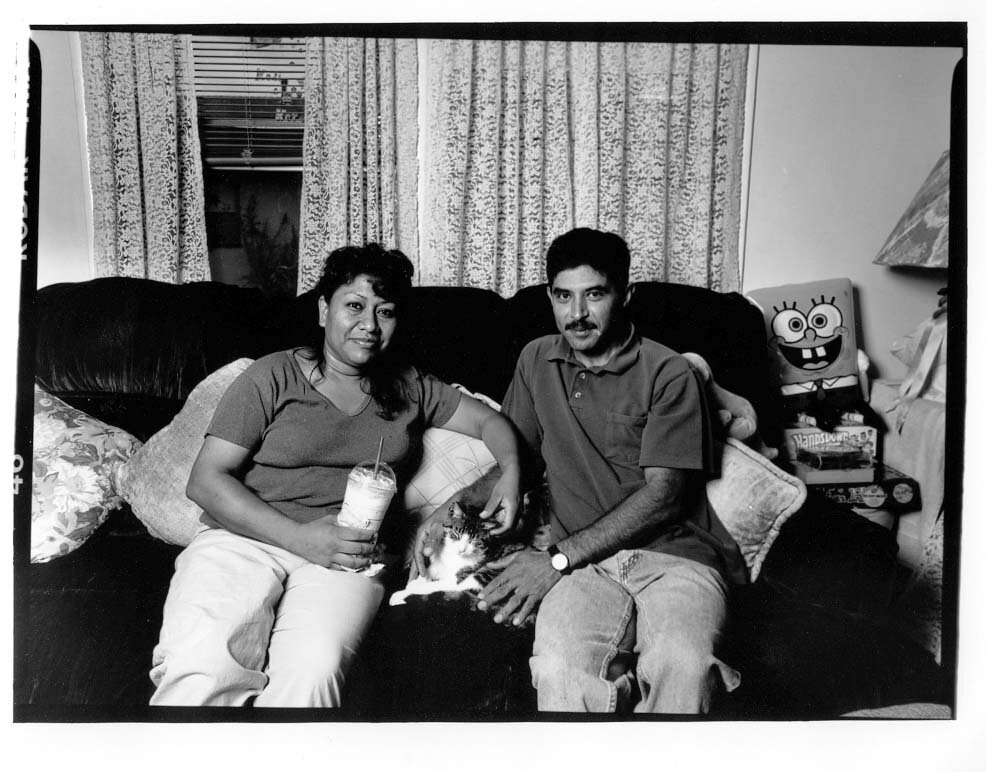

From the outset, the students had taken many of their photographs at home. The third assignment, which called for a portrait to accompany an interview with a family member, absolutely required it. Either way, these photographs taken in the homes, and the writing that accompanied them, encouraged the students to explore their families and communities in a way that made the obvious seem new to them.

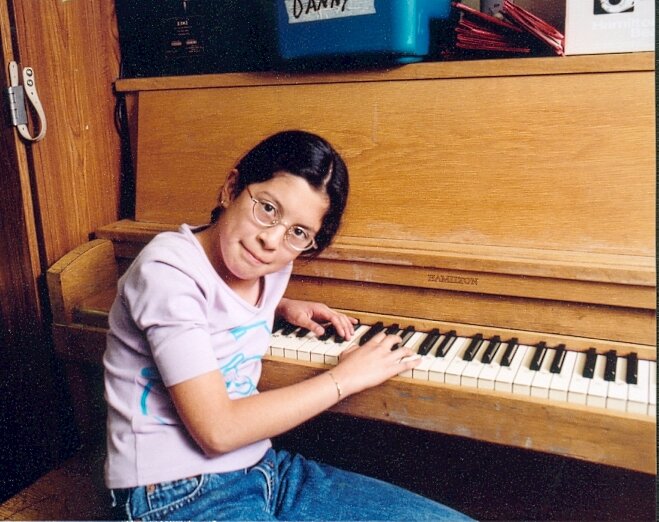

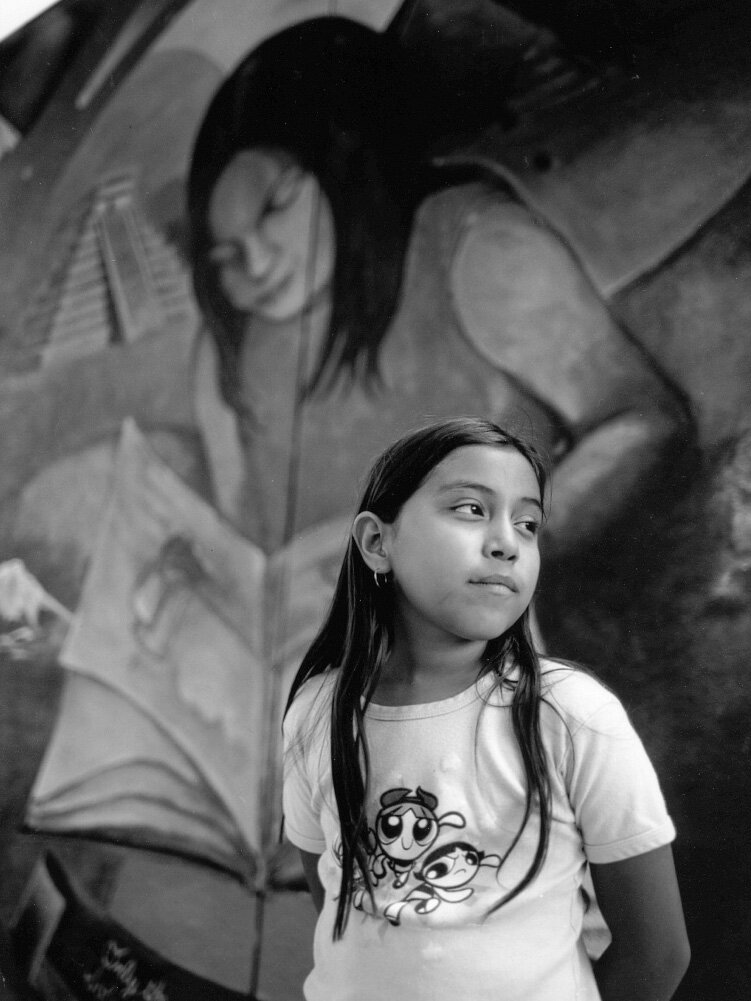

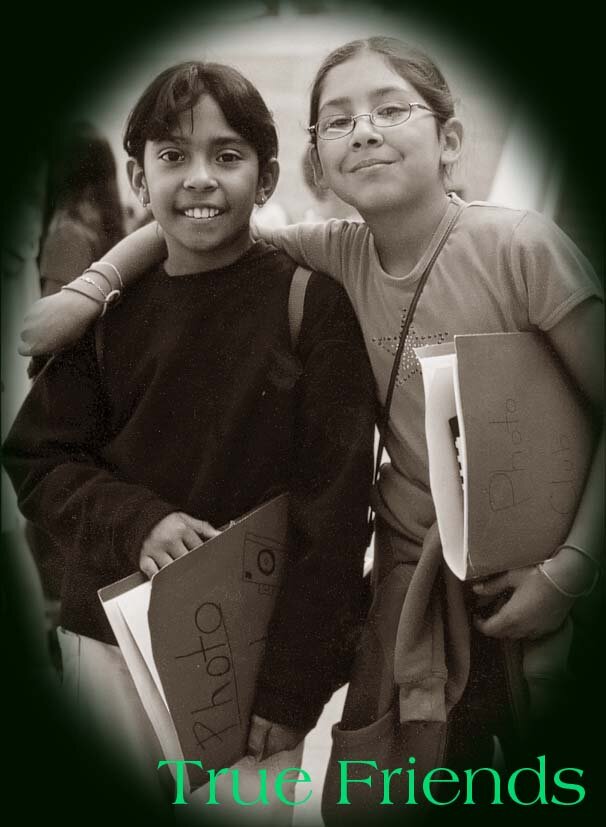

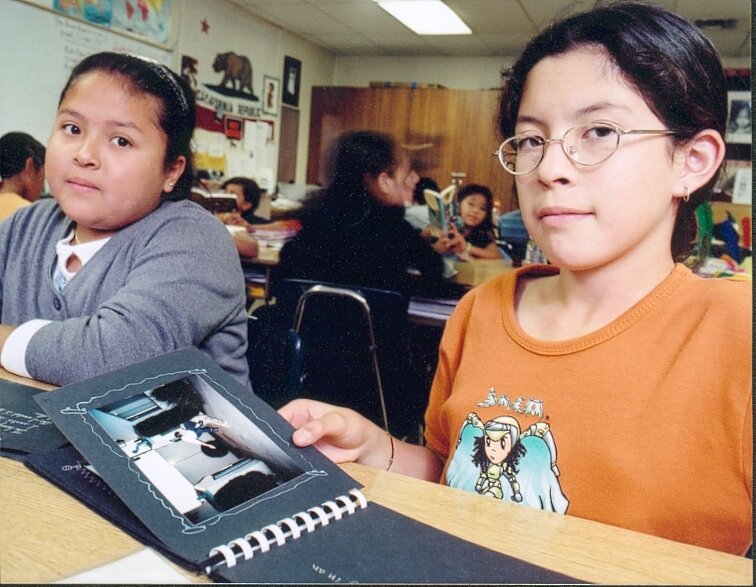

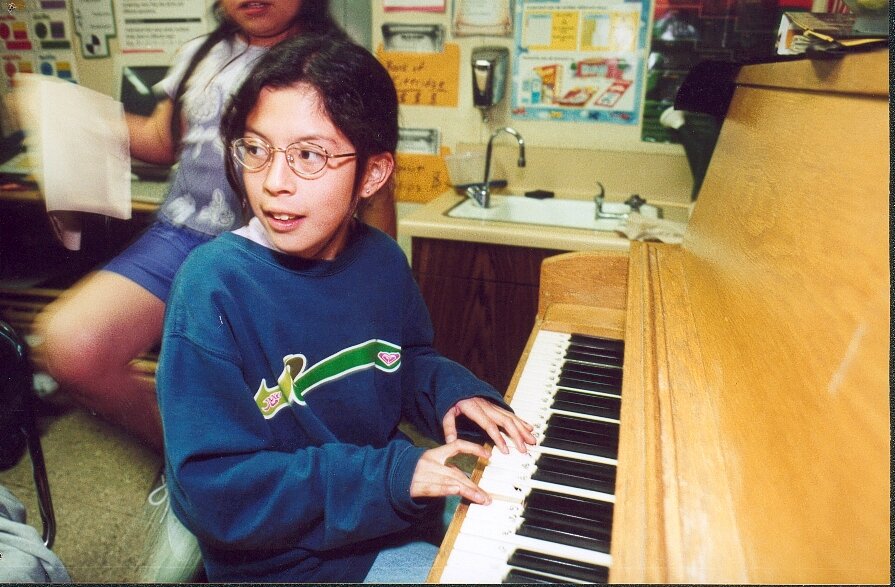

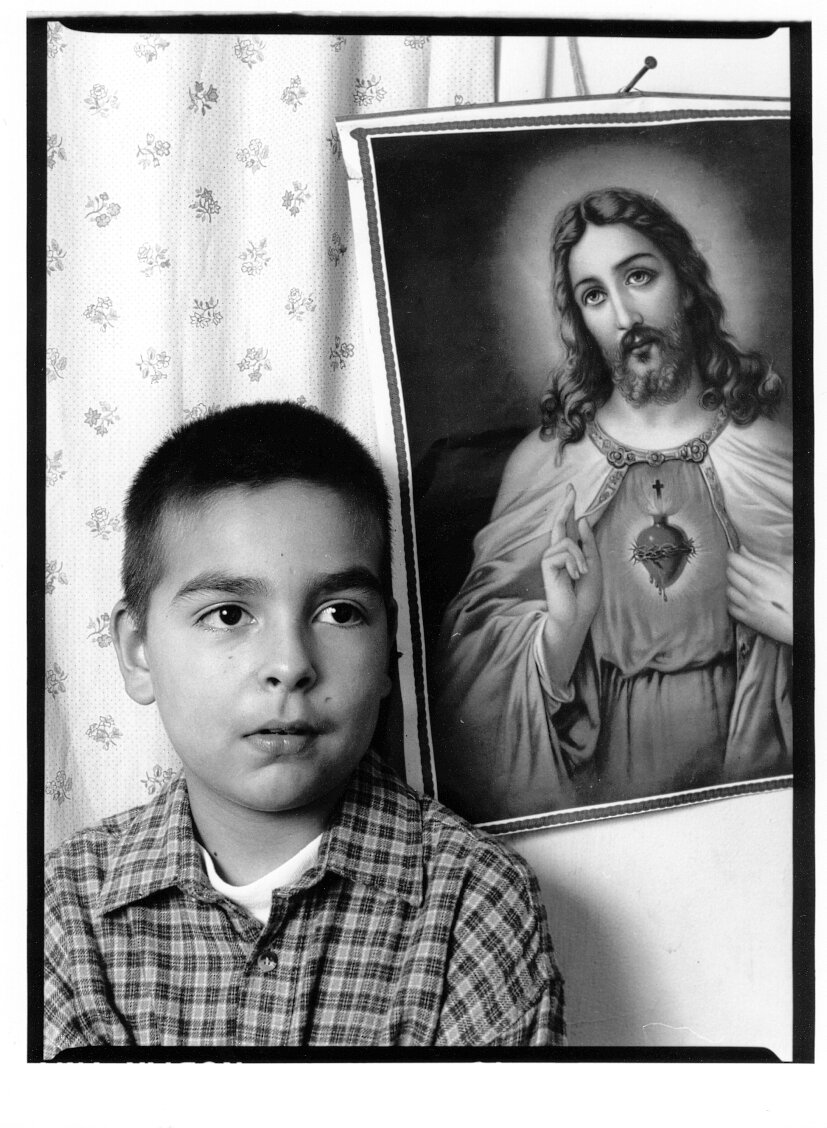

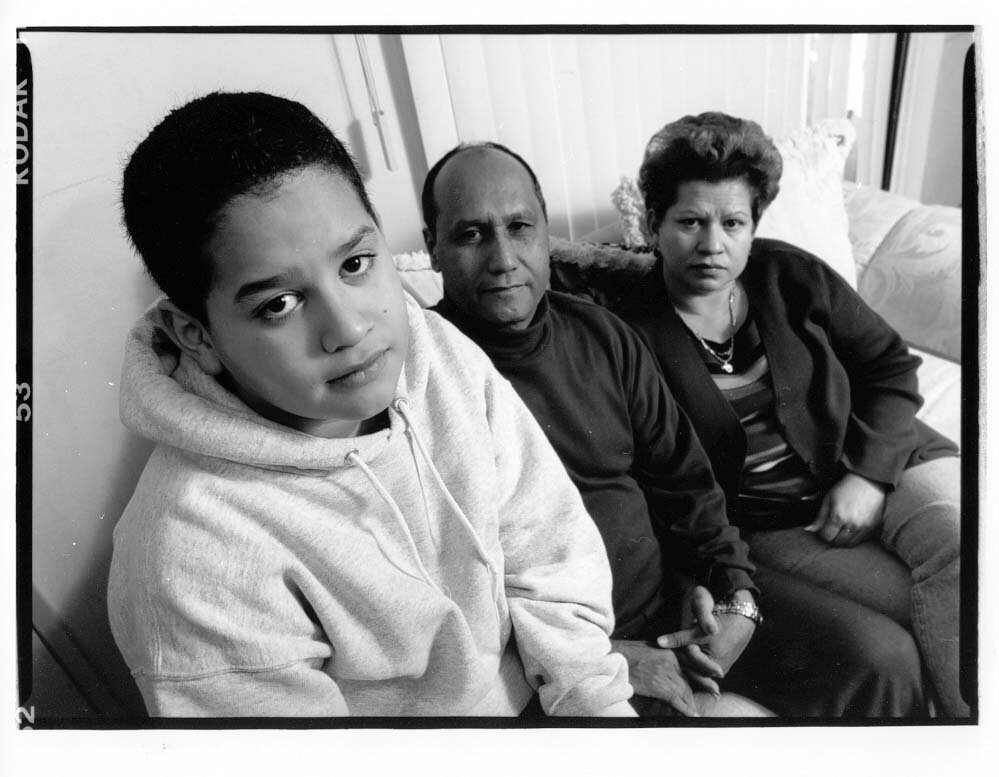

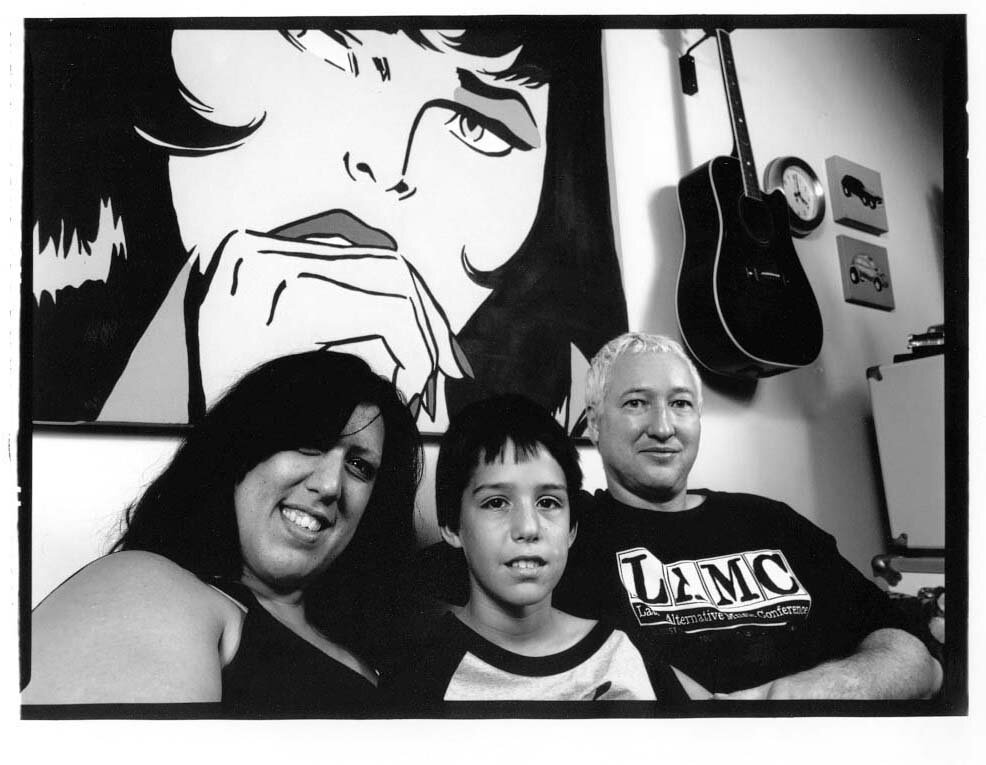

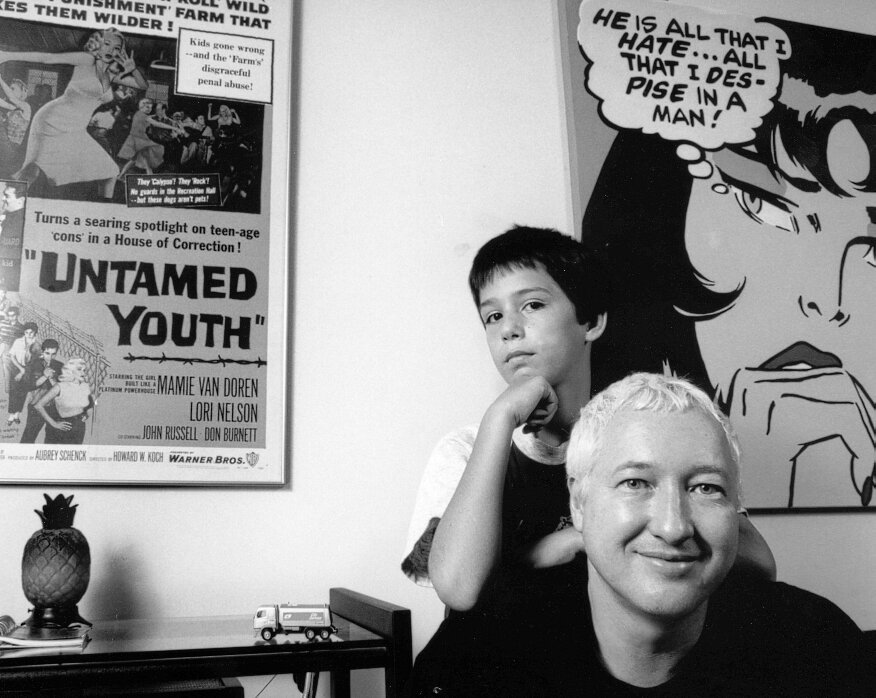

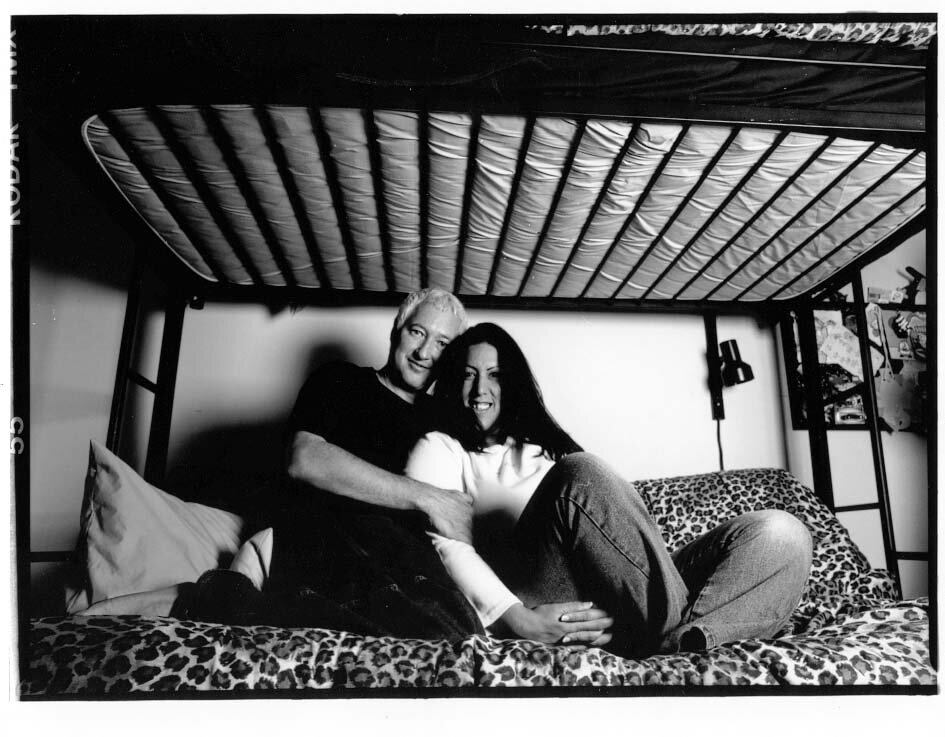

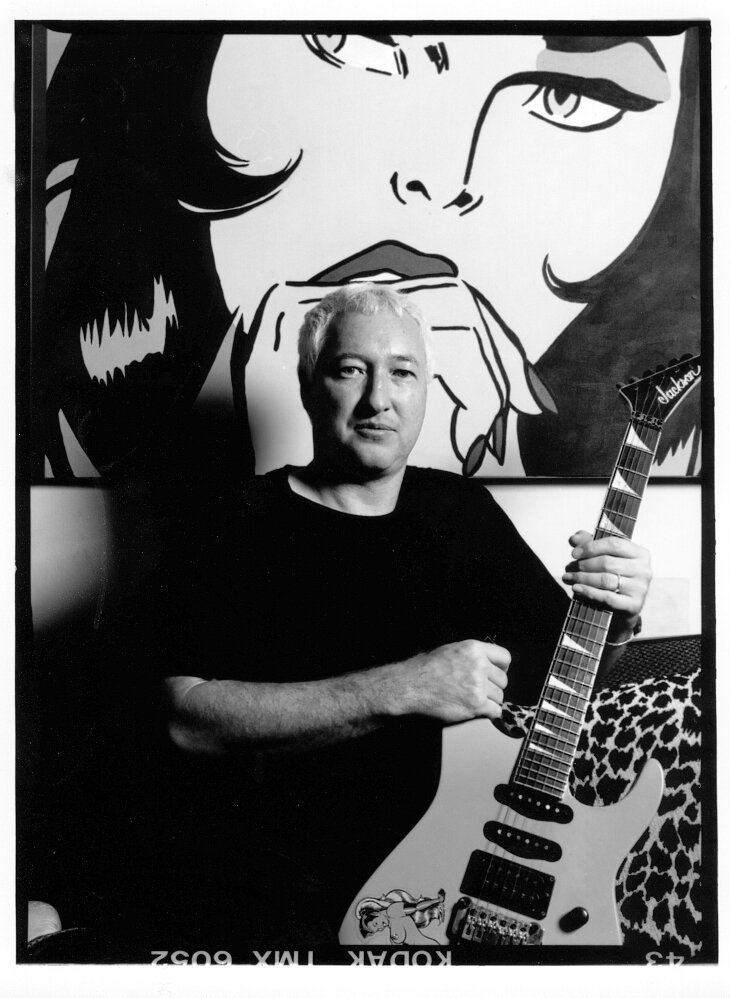

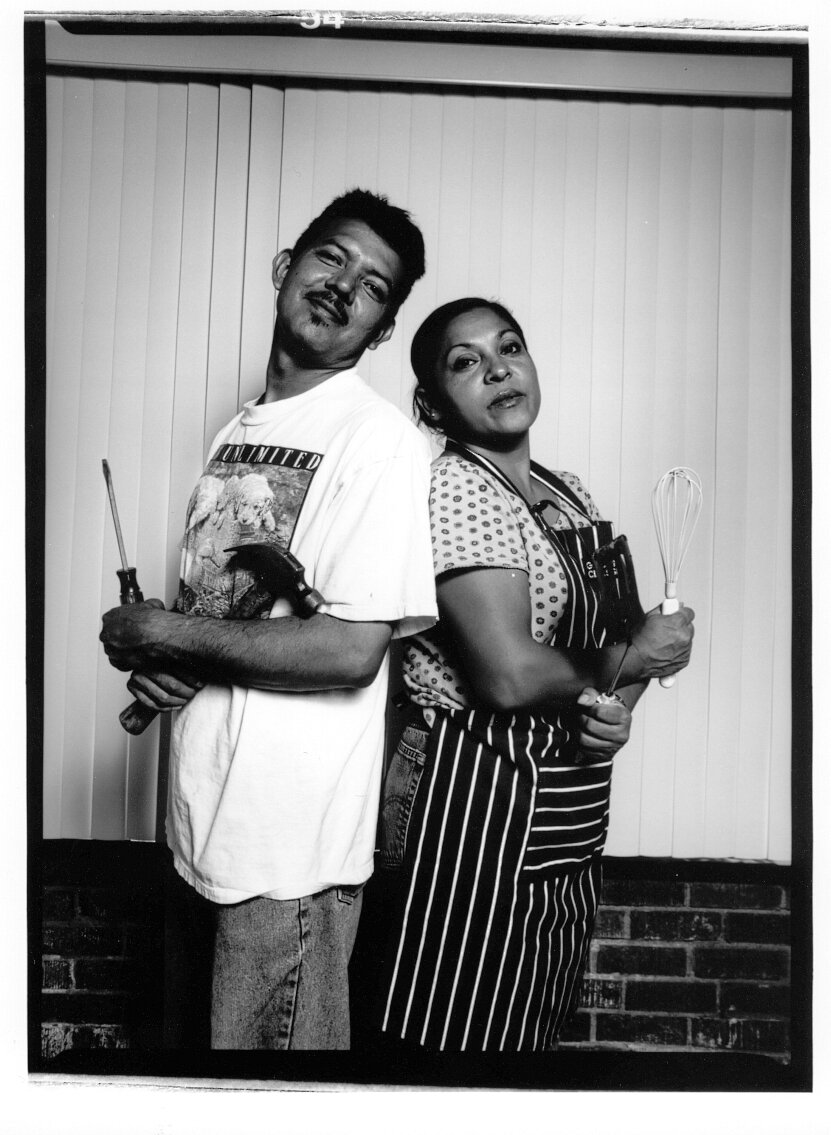

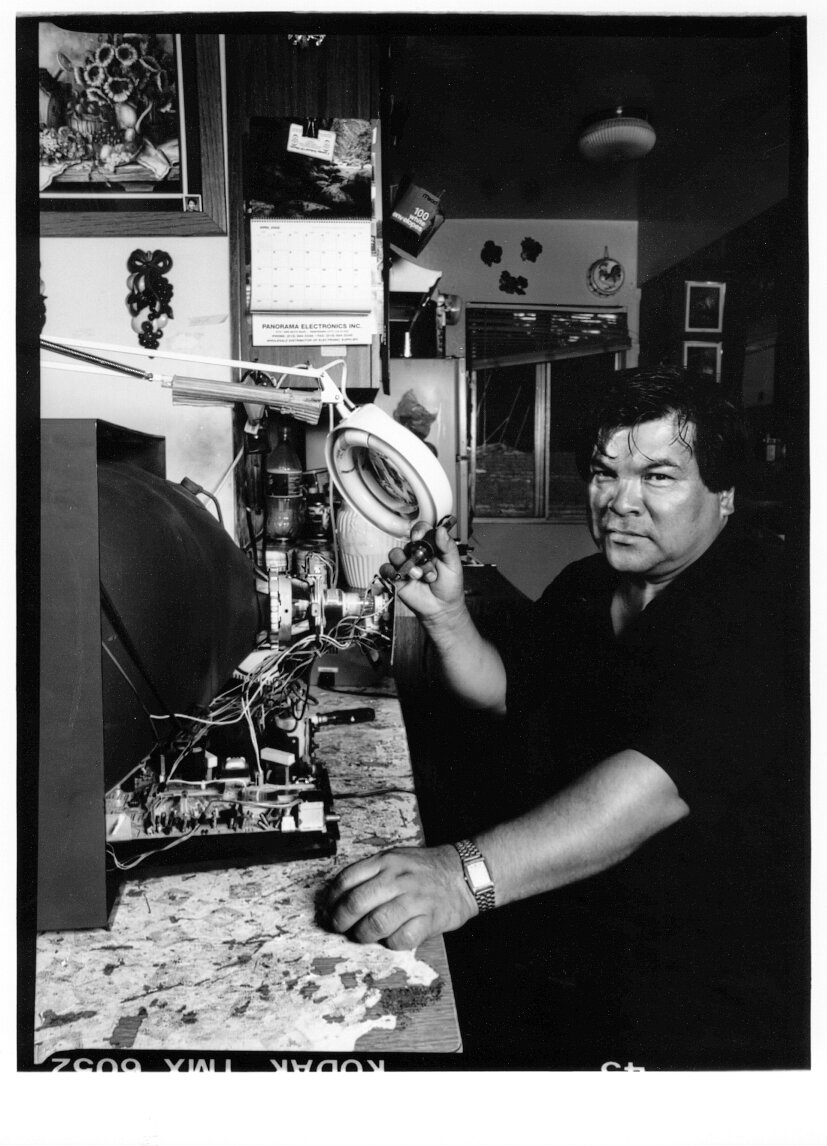

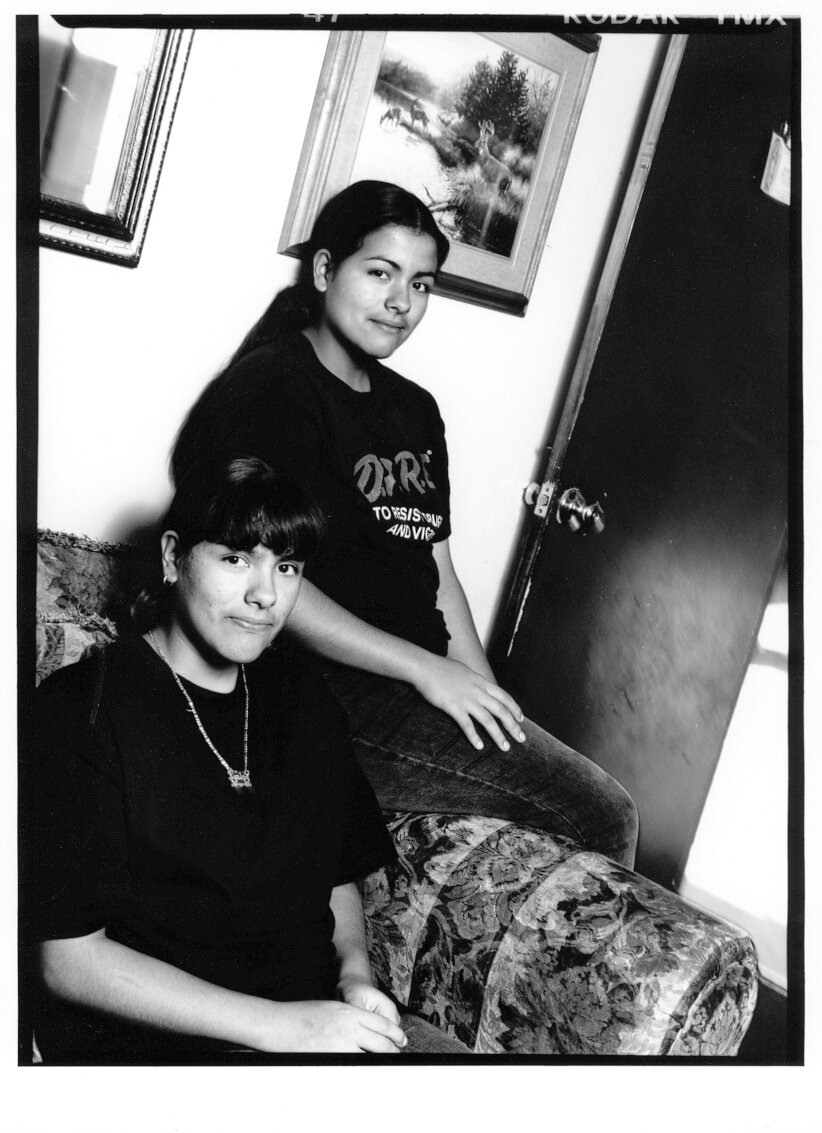

As the Kittridge Photography Club progressed into its second year (I kept the same students together as we moved into fifth grade) the project began to evolve beyond the objectives of the original curriculum. The most significant manifestation of this was the introduction of the more sedentary, deliberate method of photography frequently associated with studio portraiture. Anxious to begin my own exploration of medium-format portraiture, I arranged a series of home visits, in which I planned to utilize portable studio lighting. Months earlier, to familiarize the students with the more sophisticated equipment, I had started bringing the larger camera, lights and umbrellas into the classroom. Over a period of a few weeks, I was able to demonstrate the techniques used in studio portraiture, while the students themselves had the opportunity to handle the equipment. The resulting portraits—some in color, but mostly black and white-- not only inspired the students to want to do the same, but caught the attention and earned the appreciation of their parents.

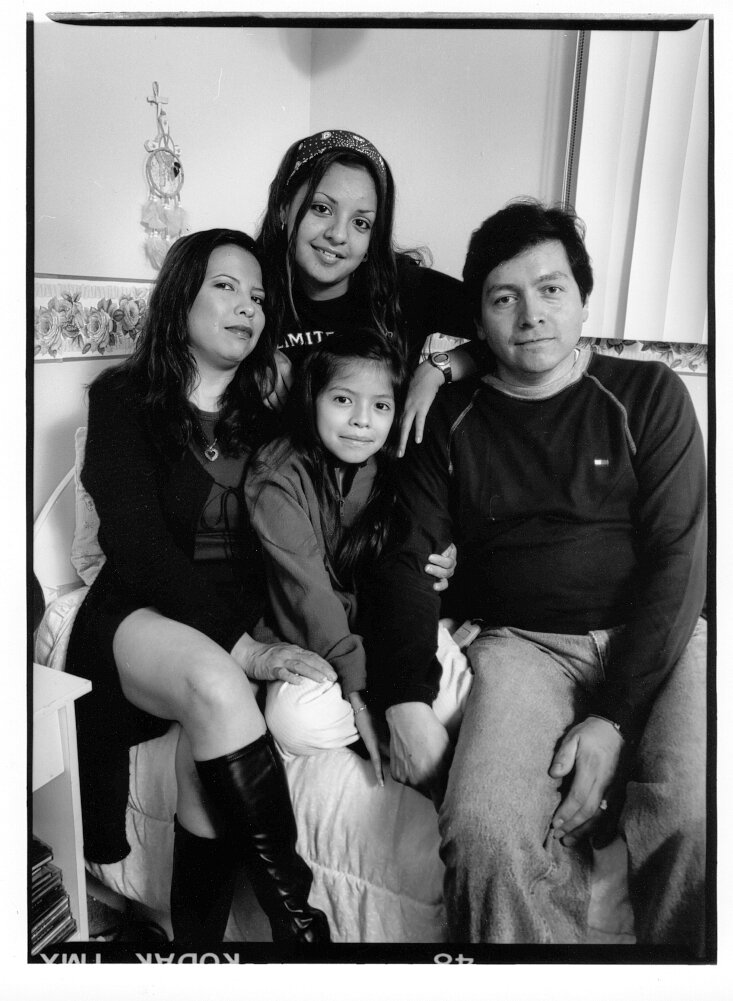

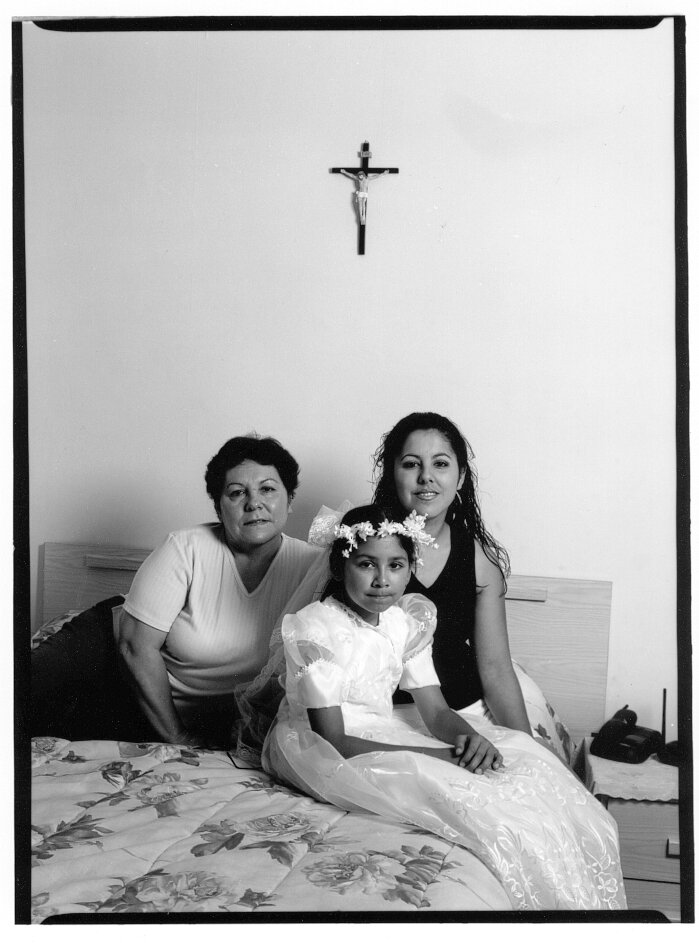

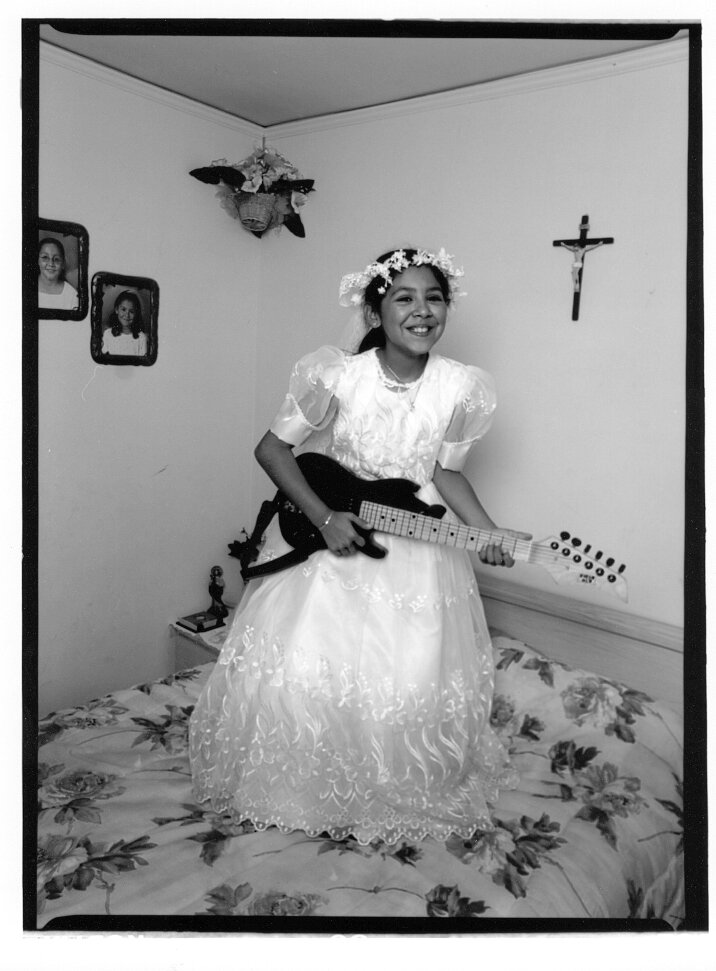

Although I had what could generally be considered an excellent relationship with the parents— some of whom I had known for as long as six years—I was still uncertain how they would react to my turning their living rooms, kitchens and bedrooms into makeshift photography studios. After all, it was one thing for “Mr. B.” to come visiting for a meal or a game of chess, and quite another to bring the searching eye of the camera into their homes. Fortunately, it seemed that all of the parents were quick to recognize the enthusiasm of their children, and the intensity with which they approached the photo sessions. It was during these visits that a real collaboration between teacher, parent, and child flourished, and a momentum began which carried us through to the exhibition. Appropriately, this phase of the project became known as Collaborations. The photographs that came out of this first round of home visits vary in the degree of formality they present. Some, like the portrait of the Alexander family, appear very relaxed, presenting an almost false candidness. In others, the families were posed in a more static, formal manner, as I tried to create images in the traditional, “family album” style. One common thread that runs through all of the photographs made in the homes was Barthes’ punctum. As with all environmental portraiture, I attempted to reveal more about my subjects through the inclusion of visual details, such as household items, wall hangings clothing, and religious iconography.

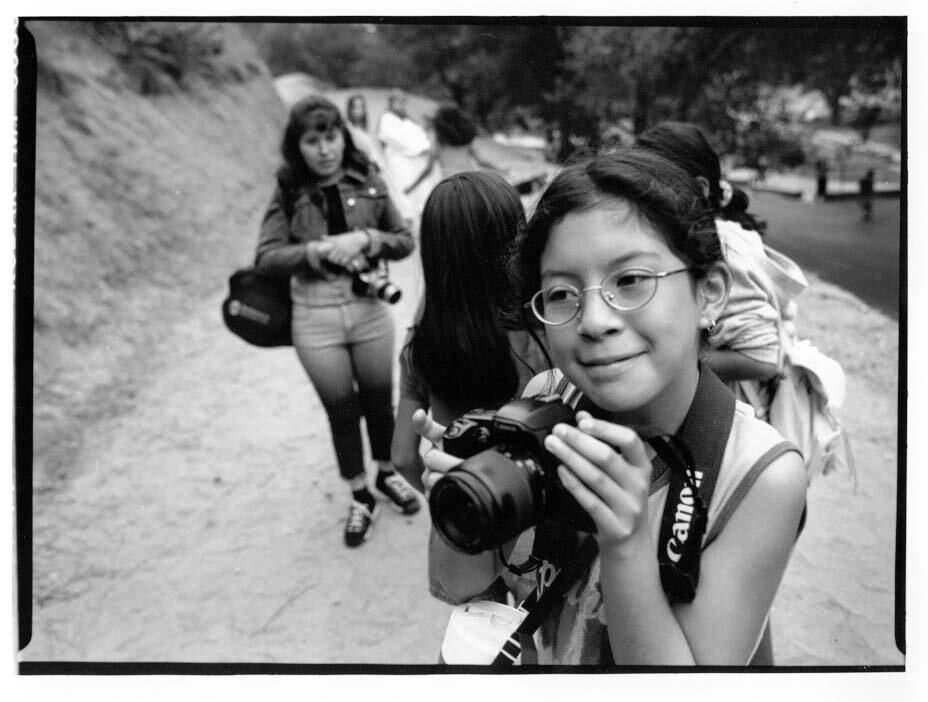

Kimmy Limon shoots a portrait of her mother using a portable studio set-up.

We eventually arranged a second round of home visits during which the students themselves used the medium-format camera and lighting, while I acted as facilitator, setting up the equipment and offering general direction. The students were encouraged to previsualize scenarios before my arrival, with the goal of creating environmental portraits of the family members.

COLLABORATIONS GALLERY (STUDENT WORK)

The resulting images are a testament to both the exactitude of the photographic process, and the individual talents of the students. Many of these portraits appear so expertly accomplished, it is difficult to tell whether they were taken by the students, or their instructor. This raised the questions about the validity of these images. It’s a reasonable question: “Could the students have made such professional looking images without intense adult supervision and instruction?” My opinion is that of course they couldn’t have, but this should not diminish the results. When using fully automatic, fixed-focus cameras, as most amateur or untrained photographers do, the camera takes care of important technical details such as focus and exposure. By ensuring that the lighting was correct and that the light meter was properly used, I saw myself in essence acting as a giant automatic camera. My impression was that this was even more challenging for the students, as the Pentax 645 camera is far bulkier and heavier, and needs to be manually focused. More importantly, these are questions of technology and methodology, not central to the key issue. Certainly, these portraits could have been made with any camera, any equipment, but they could not have been made without the collaboration between parent, teacher and student. The children, as photographers, still had to conceptualize, direct and relate to their subjects. The parents, siblings and other relatives, as subjects, were also active participants in an act generally perceived to be beneficial not only to the students, but to the posterity of their families. Therefore it was the process of making the photographs — the social act itself — that gave the greatest value to Collaborations.

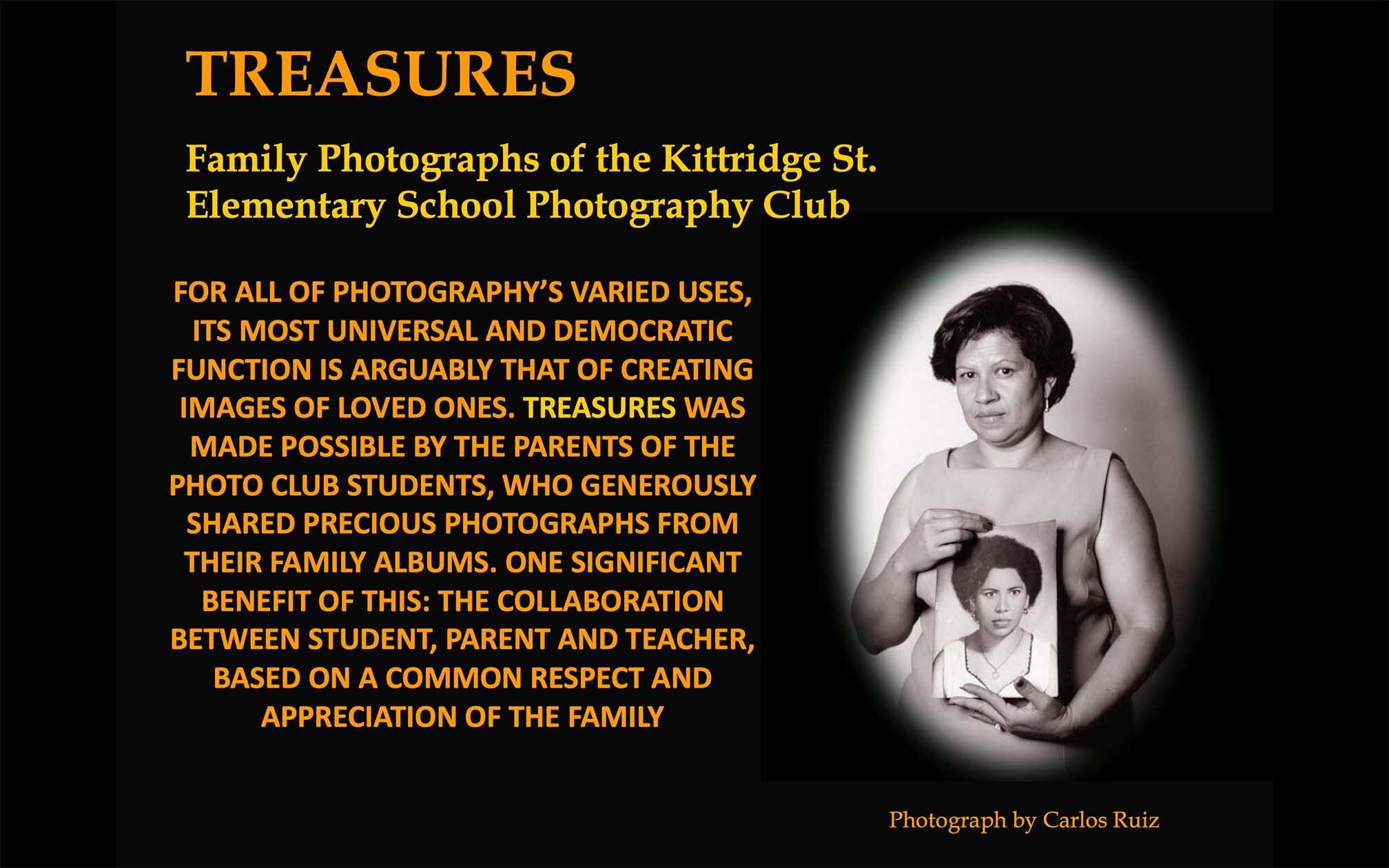

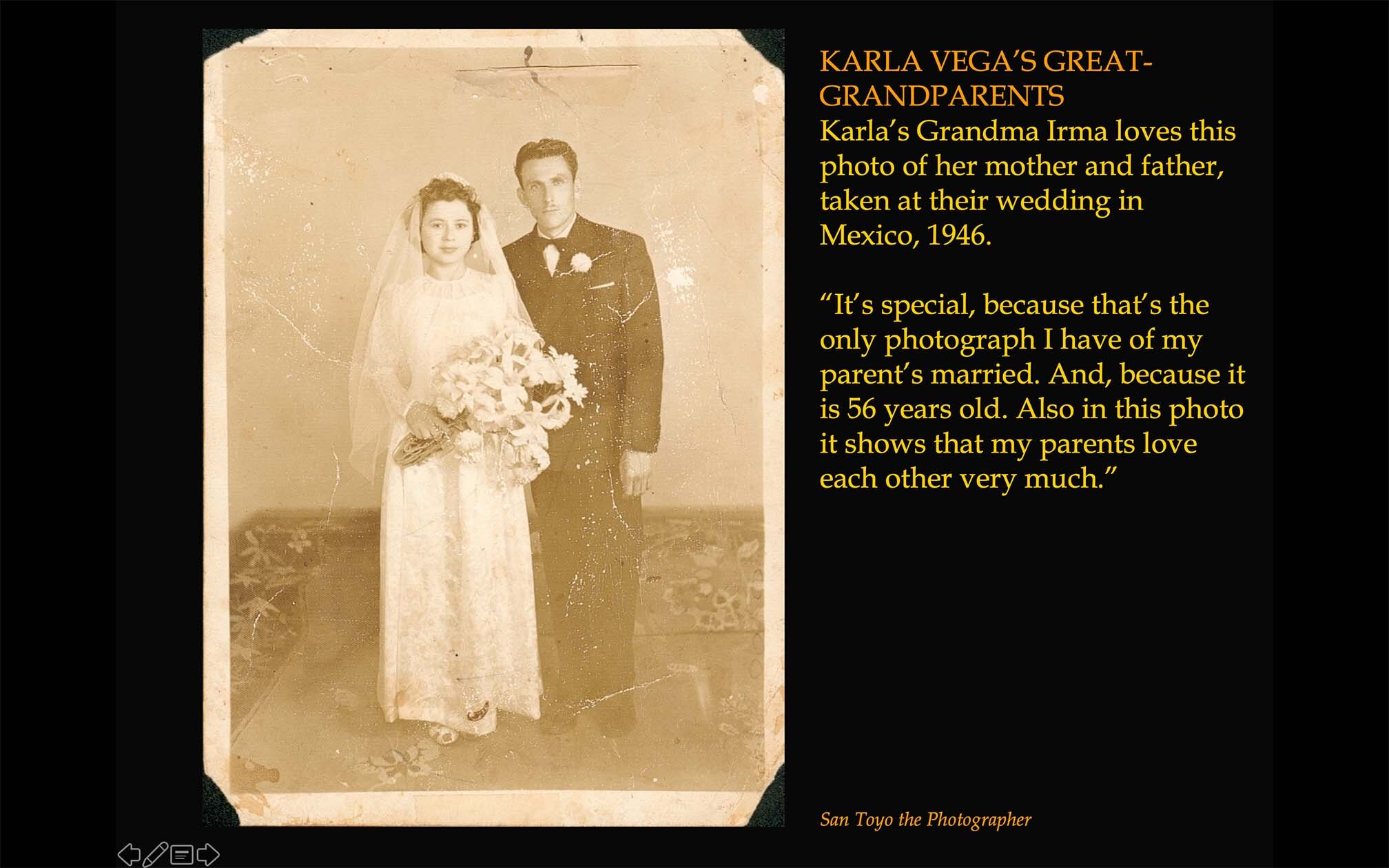

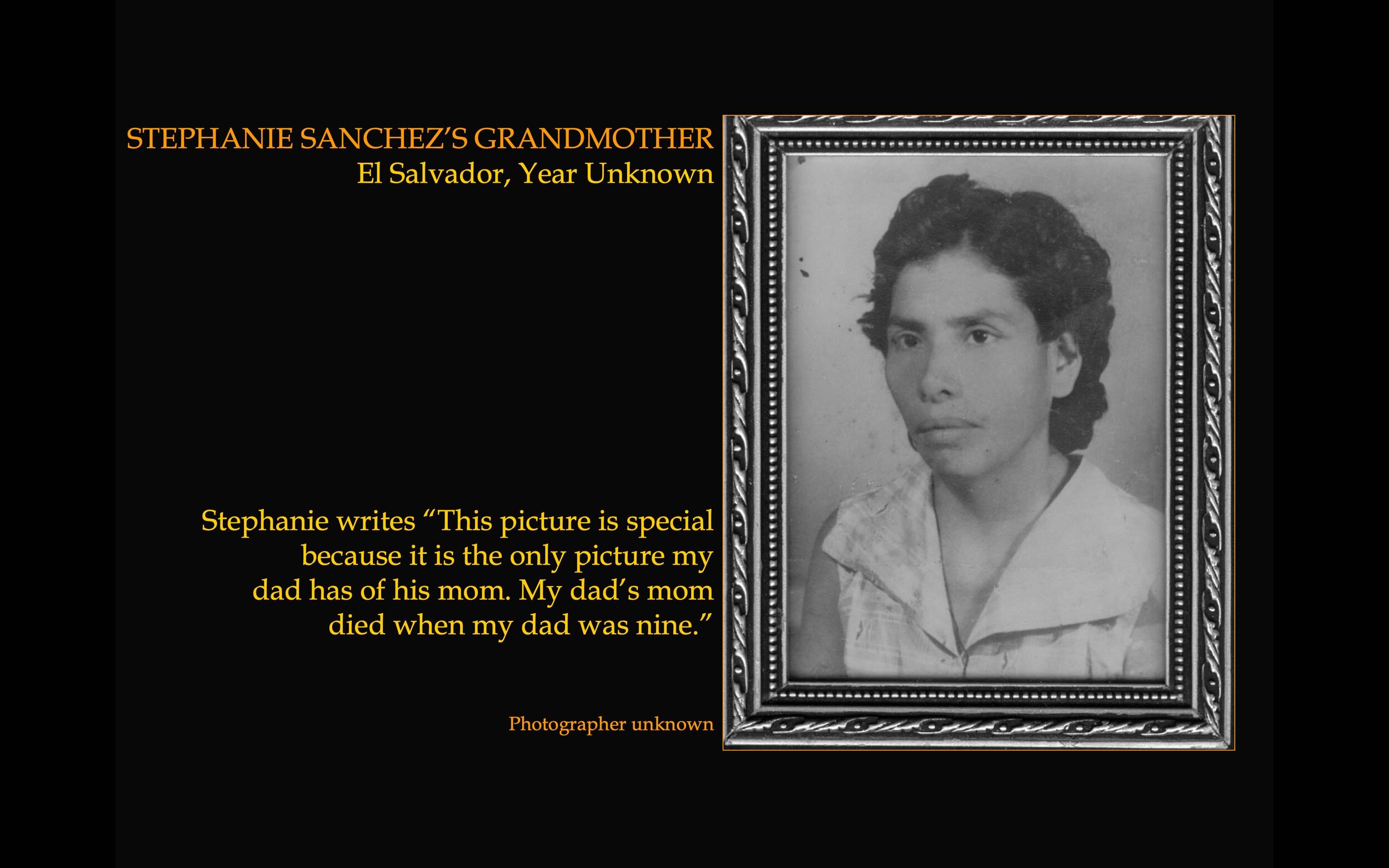

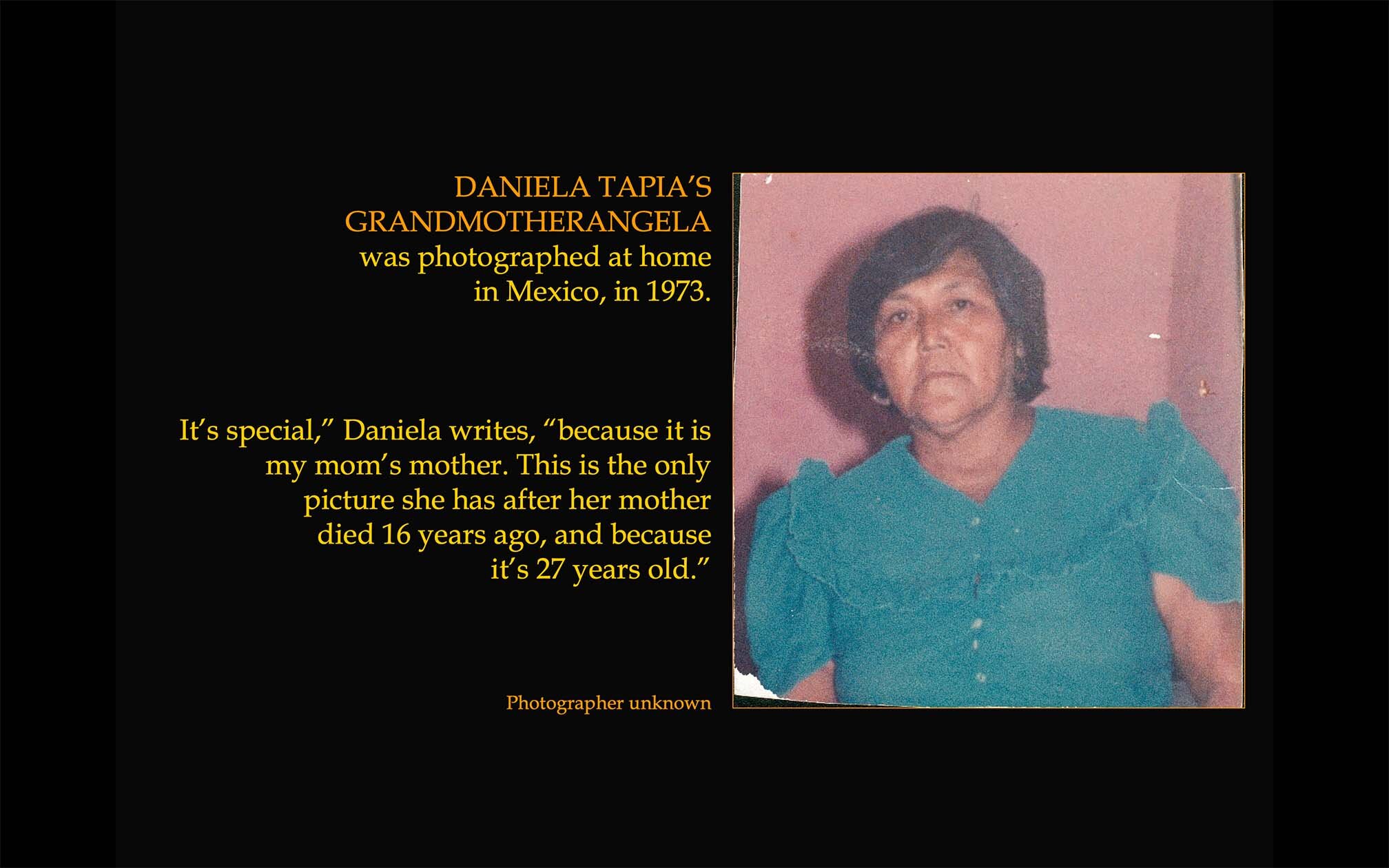

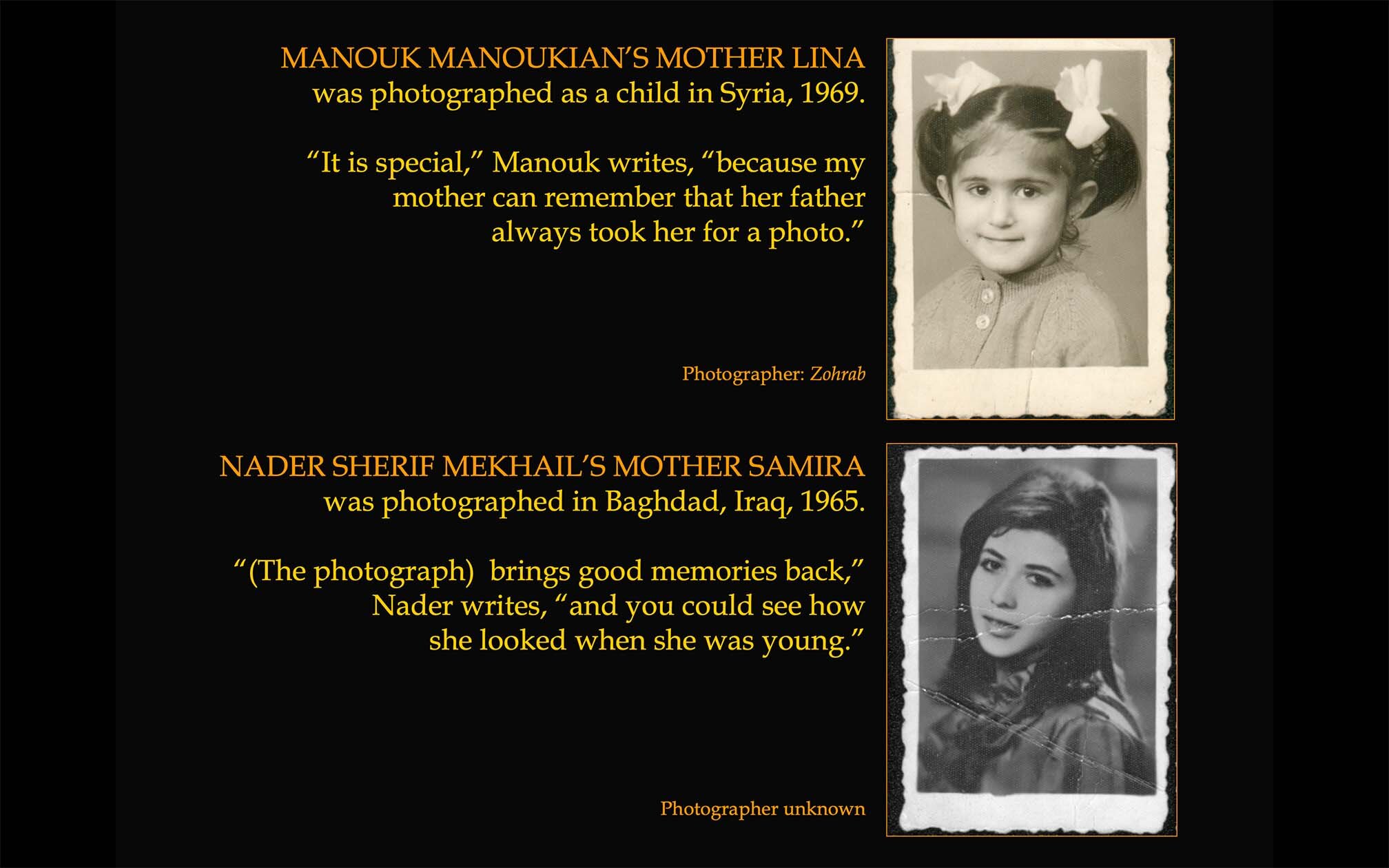

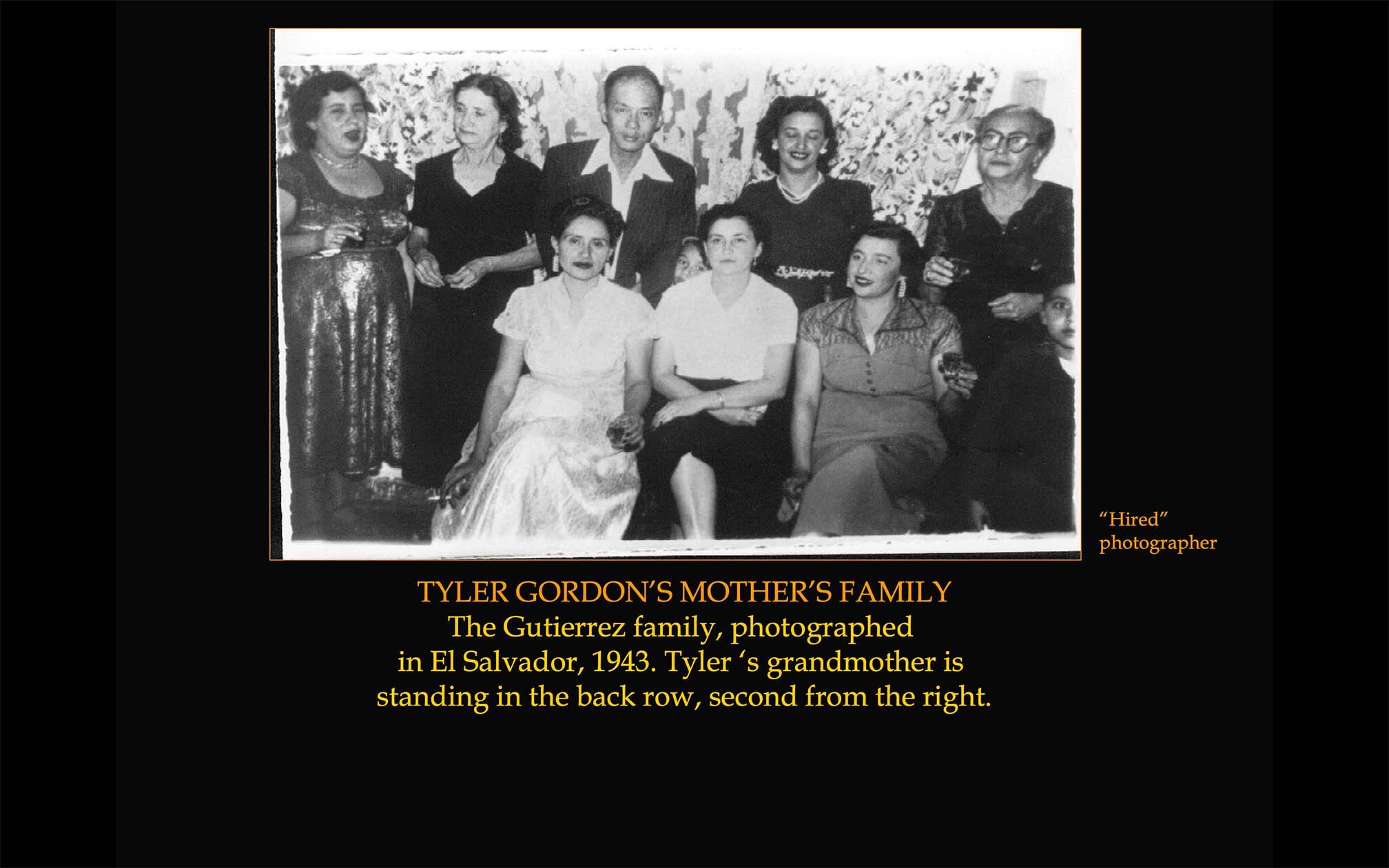

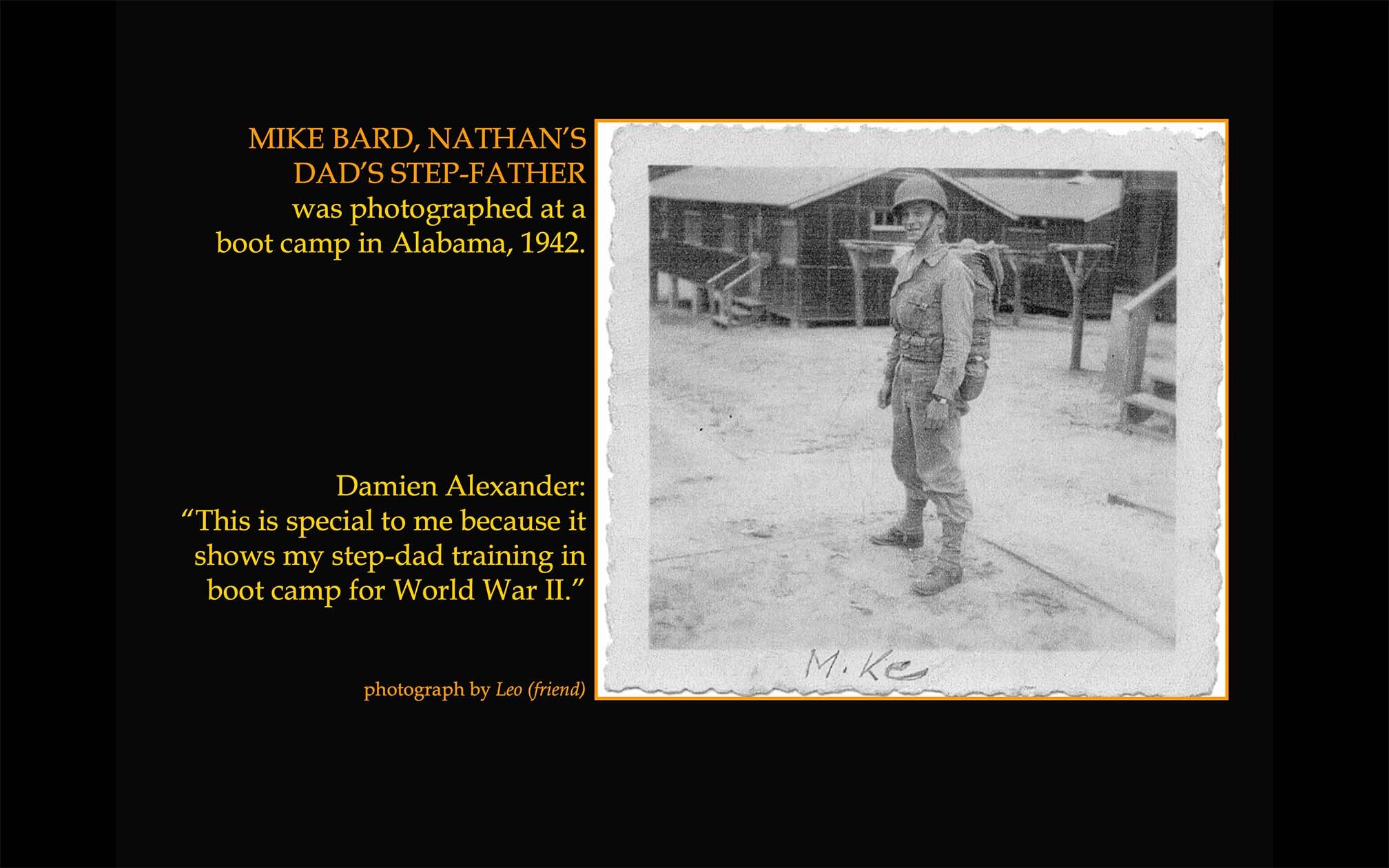

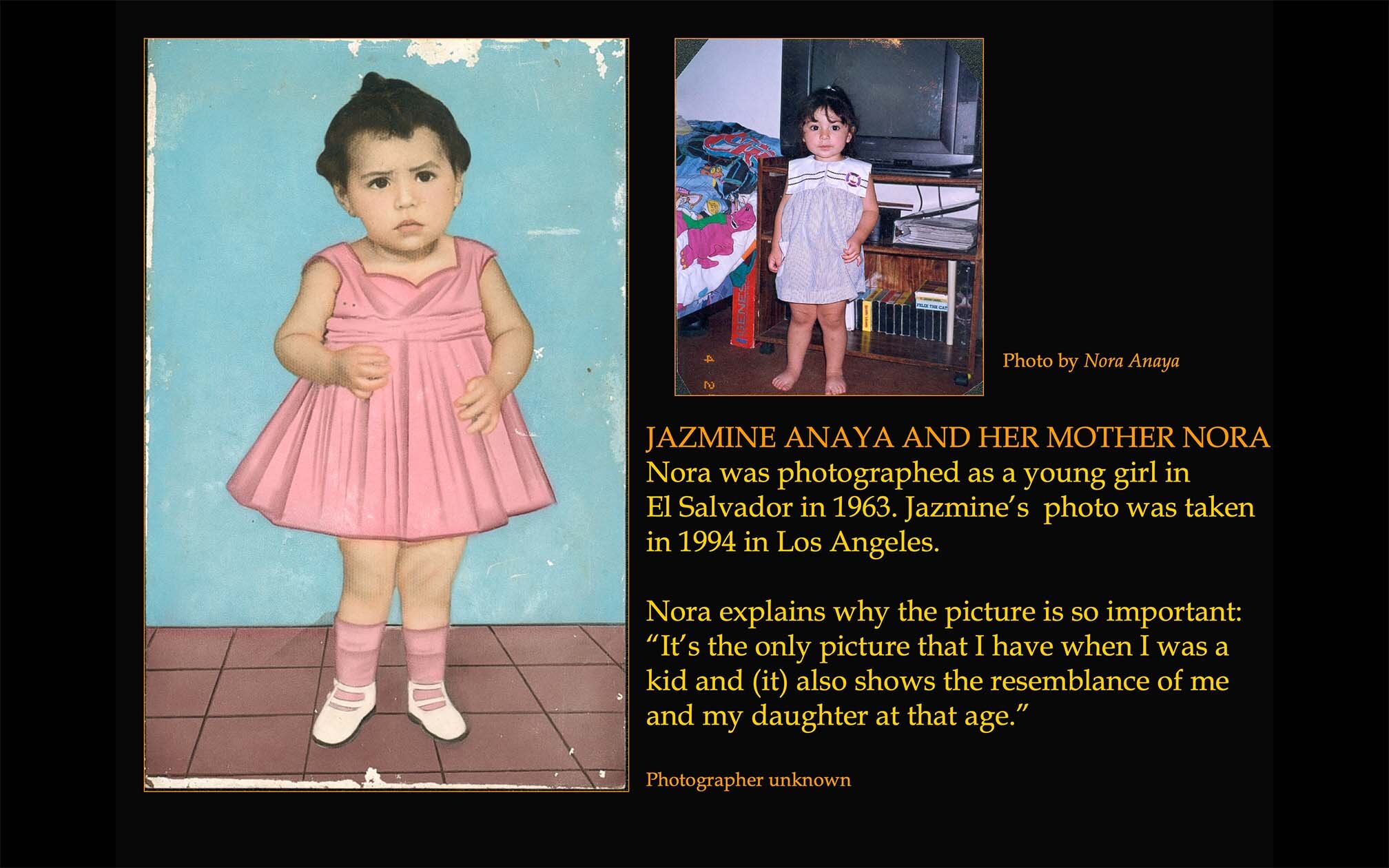

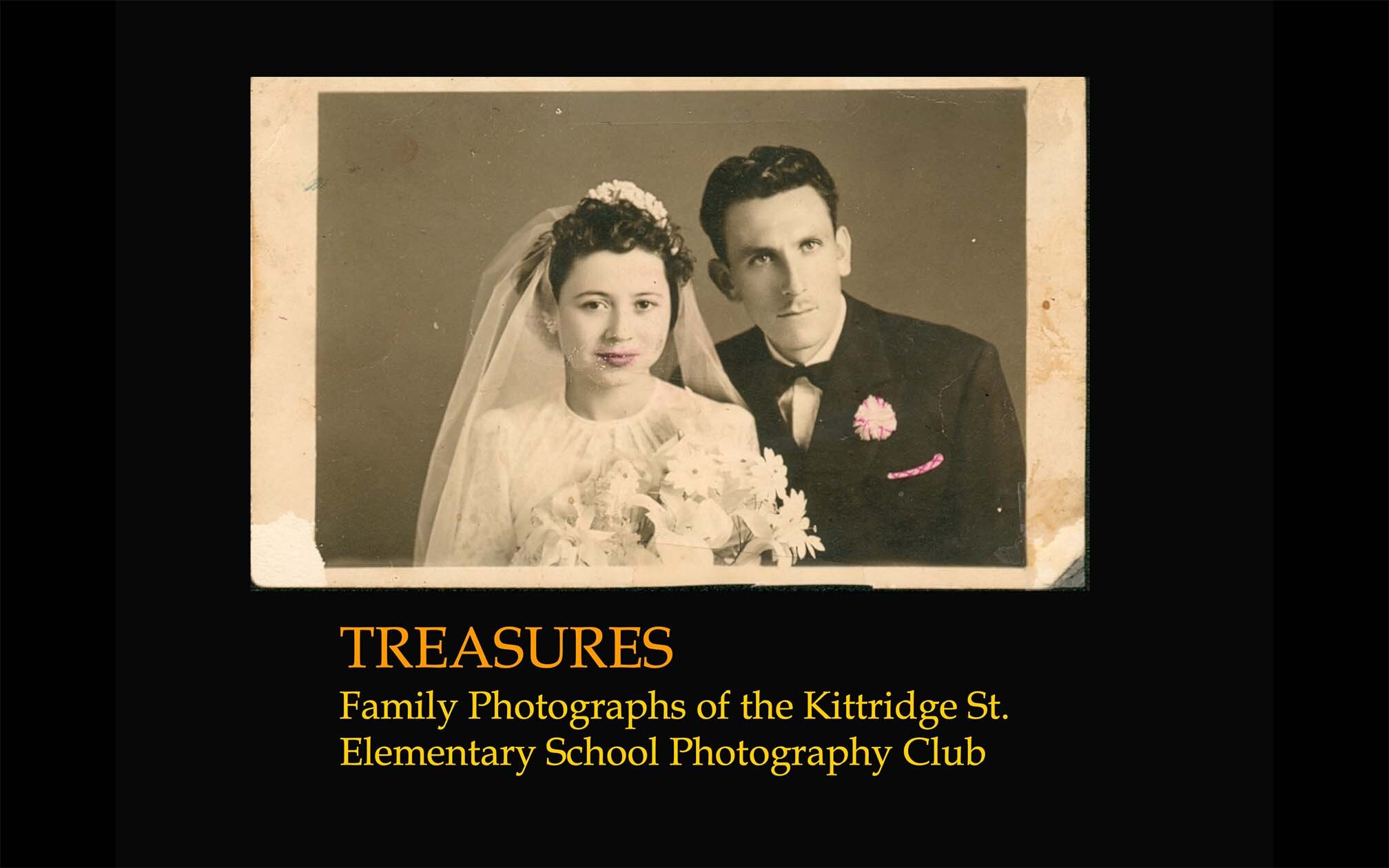

TREASURES: PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE FAMILY ALBUMS

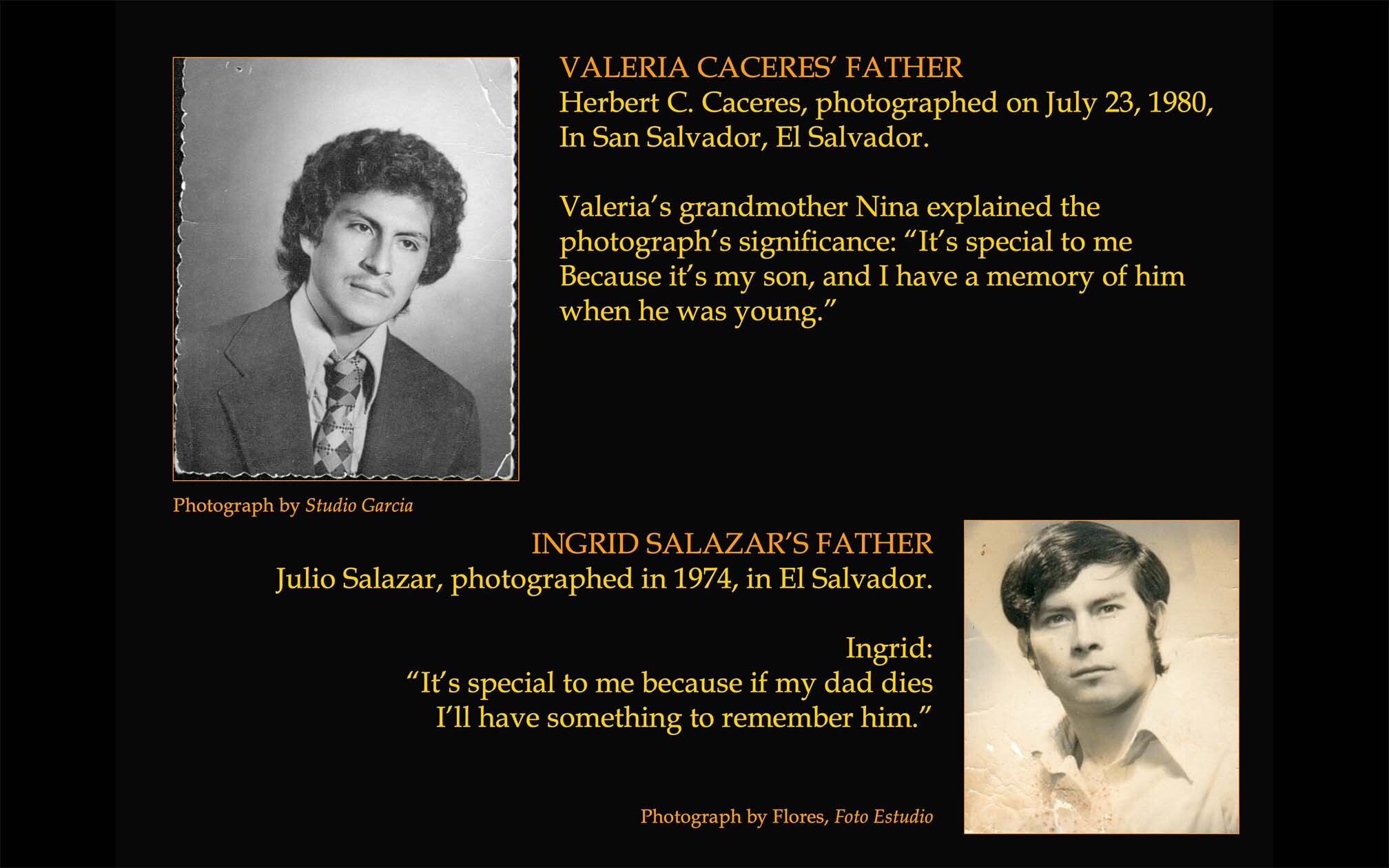

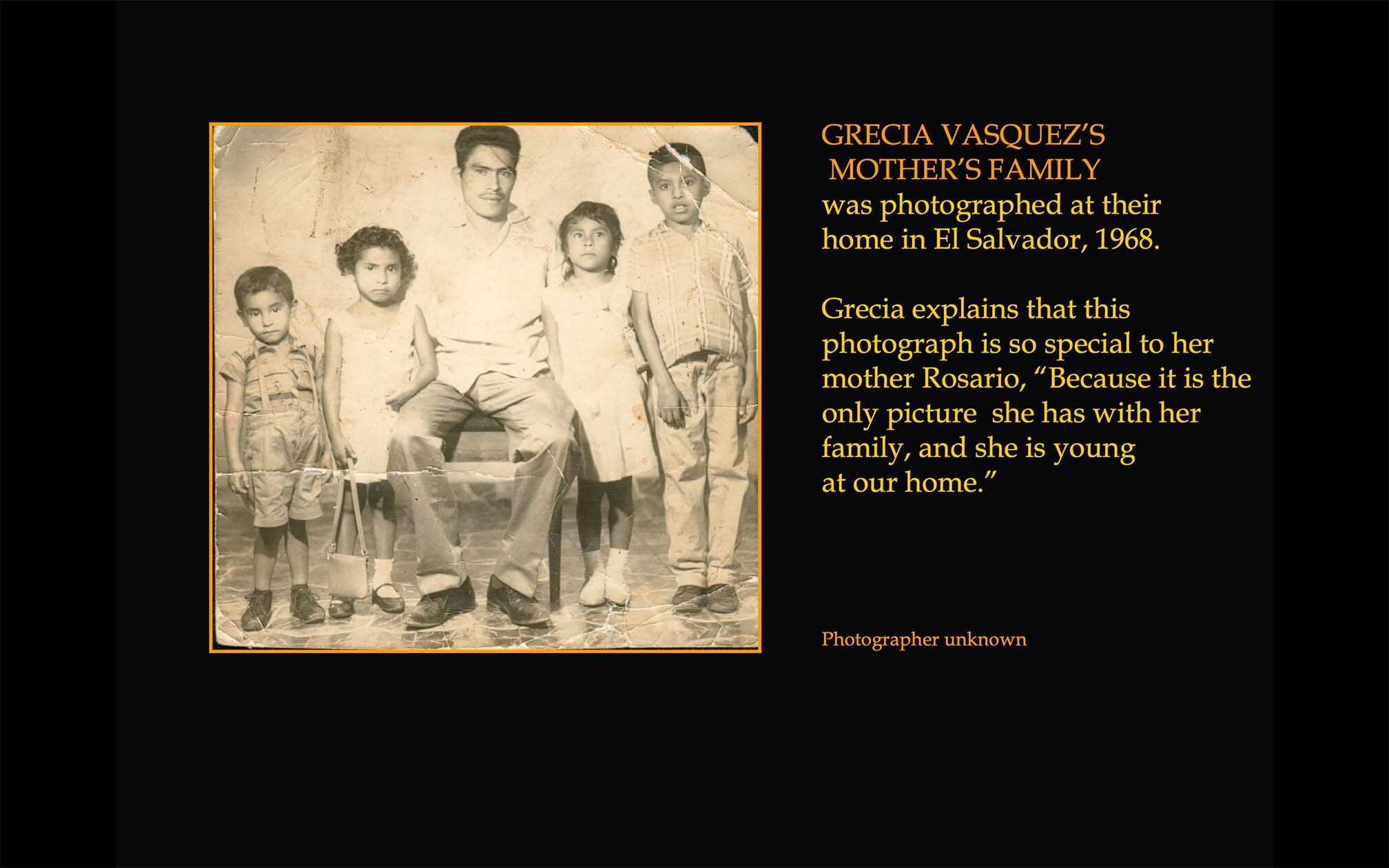

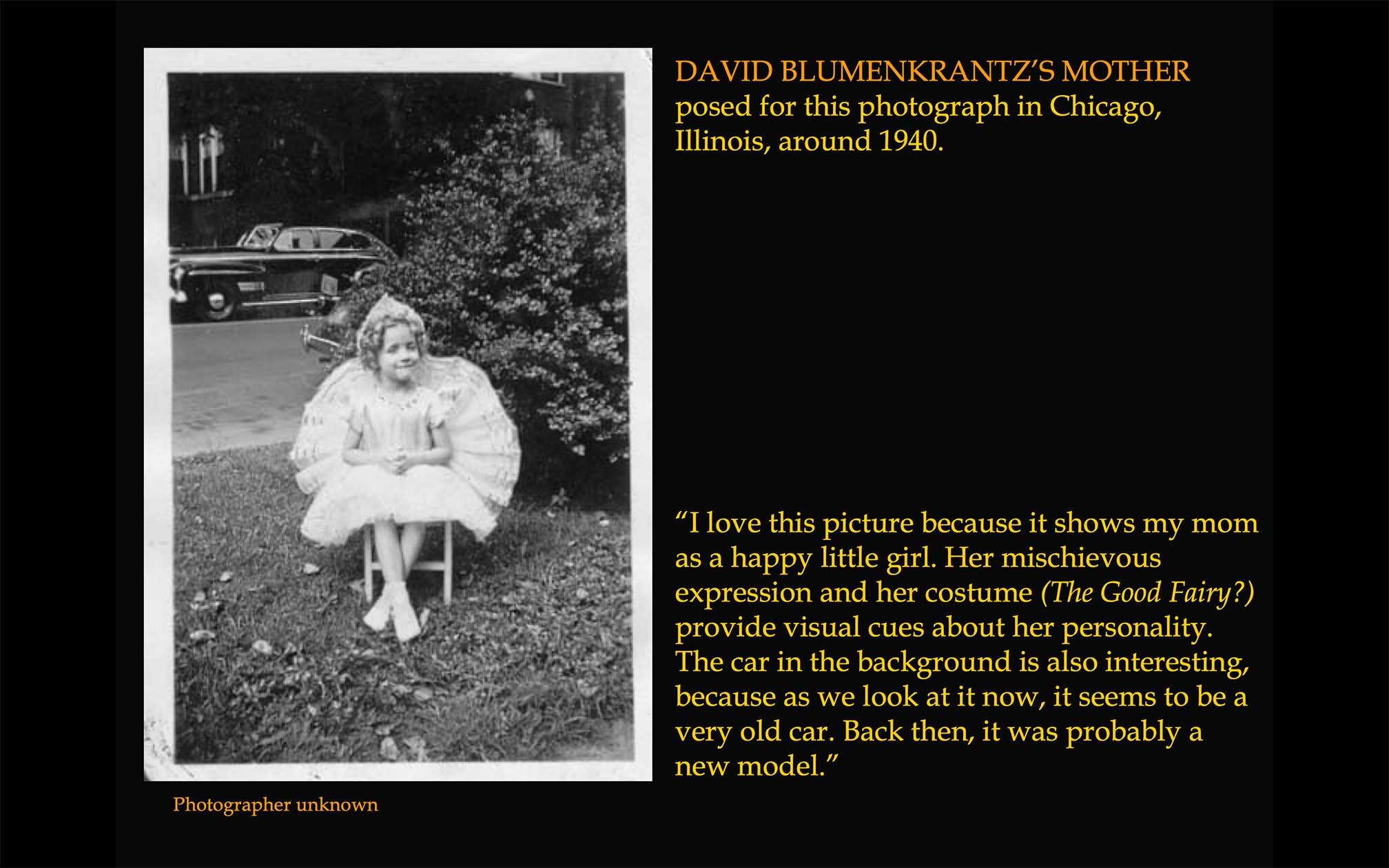

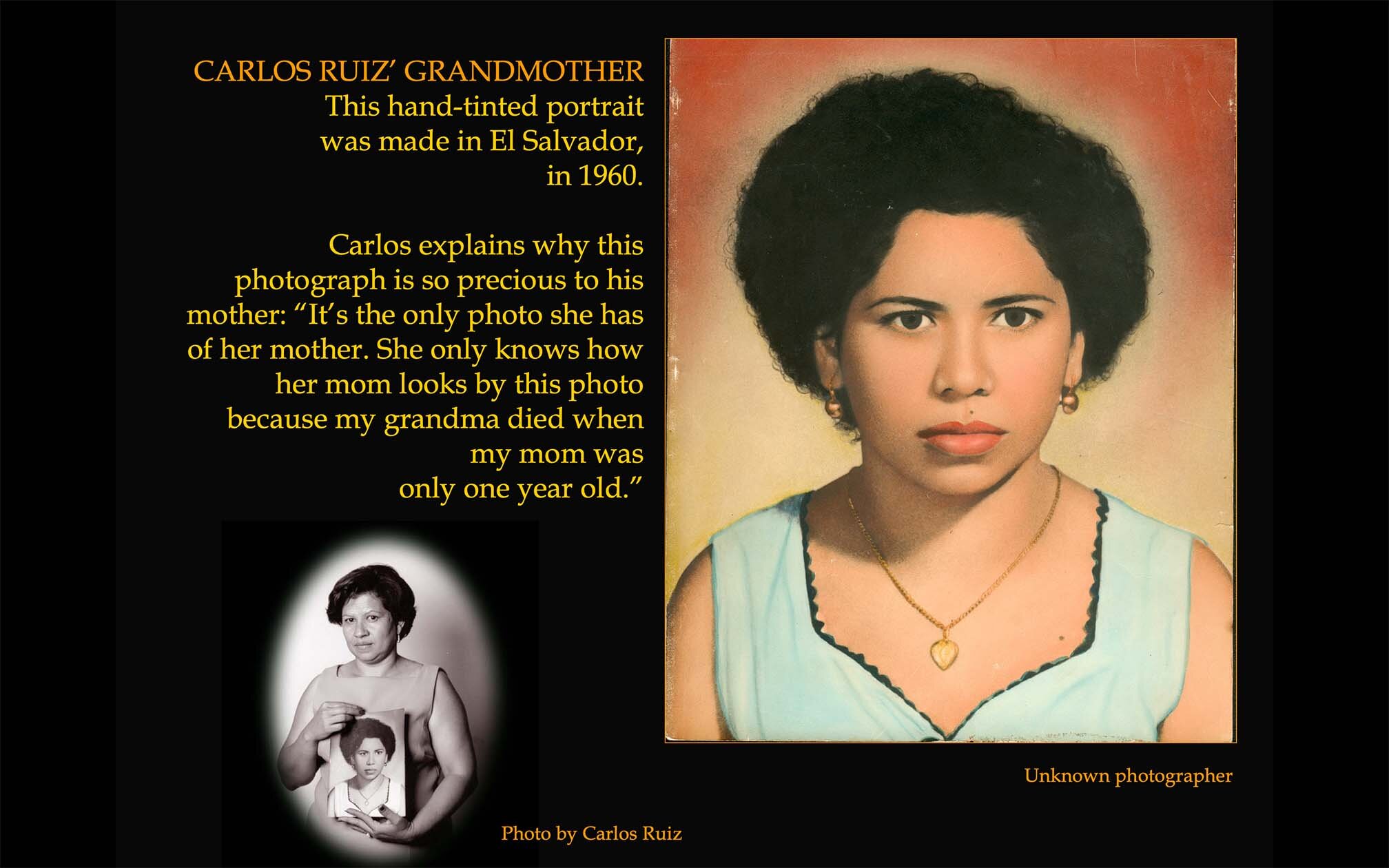

During the Collaborations sessions, the methodical procedures involved in setting up studio lighting left plenty of time for conversation. As the talk often centered around photography, invariably (sometimes without my asking, other times with light prodding) the family photo album would be brought out. Watching their parents sharing these albums with their teacher seemed to increase the students’ interest in exploring the history, through photographs, of their respective families. The parents, in an organic, unsolicited manner, became participants in the educational process. This evolved into the Treasures segment of “The Way We See It.” The Photo Club members were given the assignment of bringing one photo each from their family’s collection. These photographs are remarkable, in much the same way the Hanna Wanjiru image is remarkable. Due to poor processing or fixing, along with non-archival storage methods, some of the images appear older than they really are. Photographs made in the 1960s are browning or creased in the fashion we normally associate with the antique images of much earlier generations. As with the Wanjiru photo, this deterioration seems to add to their aura, giving a sense of historical import to what were once unremarkable, rather standard examples of family portraiture.

TREASURES GALLERY

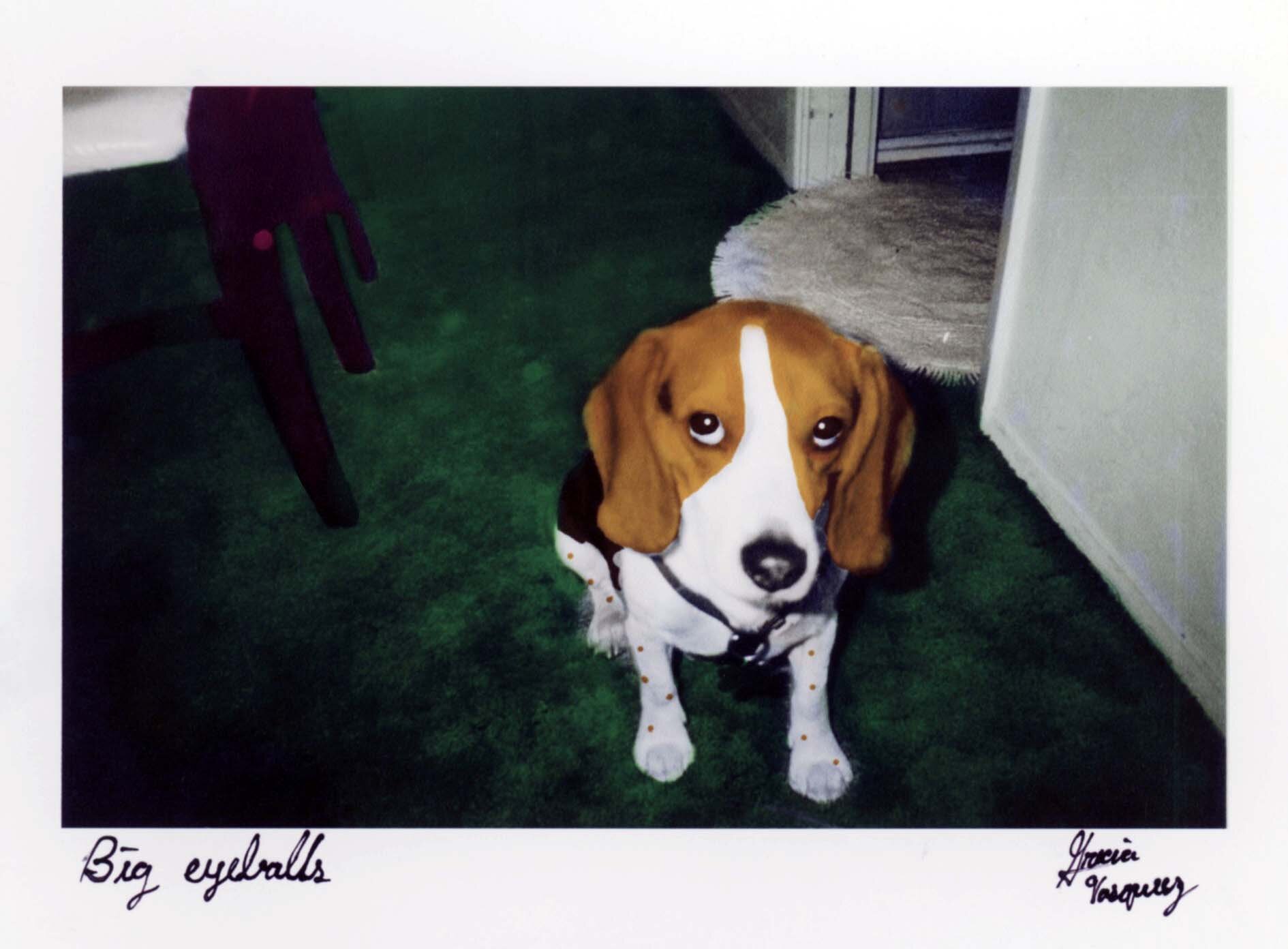

The students were also directed to interview their parents, asking them among other questions why the photograph was considered so important. The answers are touching and occasionally heart-wrenching. The testimonies of the parents consistently point to a sort of psychic bridging of the distance, in both time and space, between the photographs and their owners. A typical example: Carlos Ruiz, explaining why his mother treasures a hand-tinted image of his grandmother, taken in El Salvador in 1960, wrote, “It’s the only photo she has of her mother. She only knows how her mom looks by this photo because my grandma died when my mom was only one year old.” Of another, showing her mother as a young child in El Salvador, Grecia Vasquez wrote that this photograph is so special to her mother Rosario, “Because it is the only picture she has with her family, and she is young at our home.” All of this harkens back to Sontag’s assertion that the family photo album acts as an emotional surrogate for the extended family, now separated.

In cases where the subjects of a photograph and the possessor of the image are still together, or living in close proximity, relationships may be reaffirmed. Eva Sanchez’ mother Luz, writing about the photograph which shows her and her sister as young girls in El Salvador, wrote “This photo is very special to me because it’s a memory of my sister and I. Since we were young, we were always helping each other. It’s a reflection of what my sister and I have.” In these images, it is possible to see a common humanity. (see appendix 4, page 58)

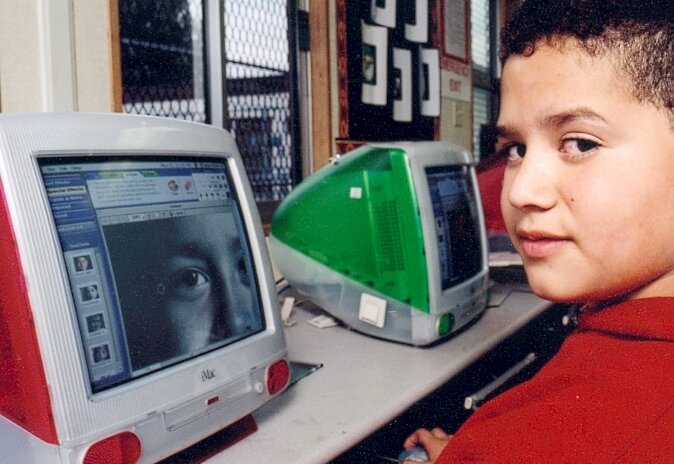

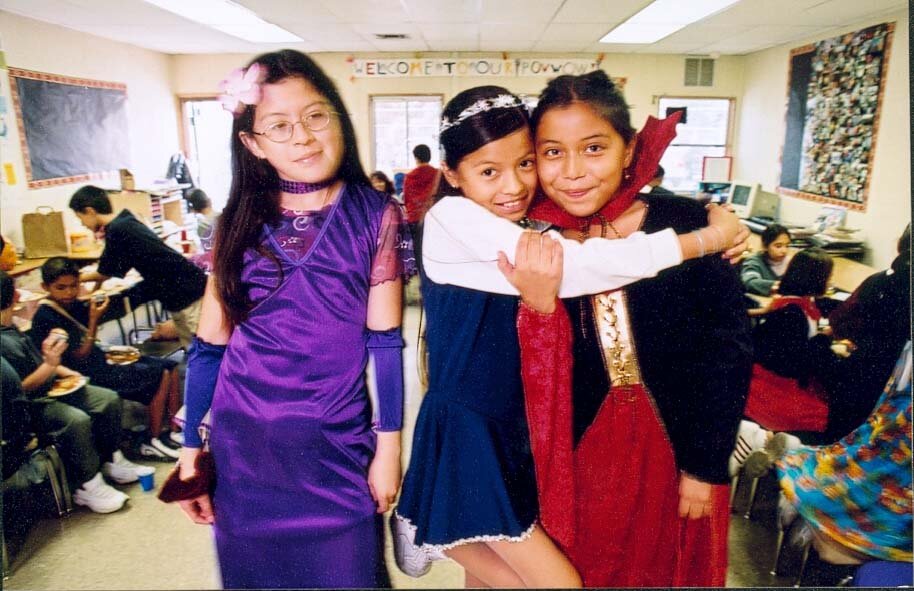

THE PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBITION AS A CULMINATING PROJECT

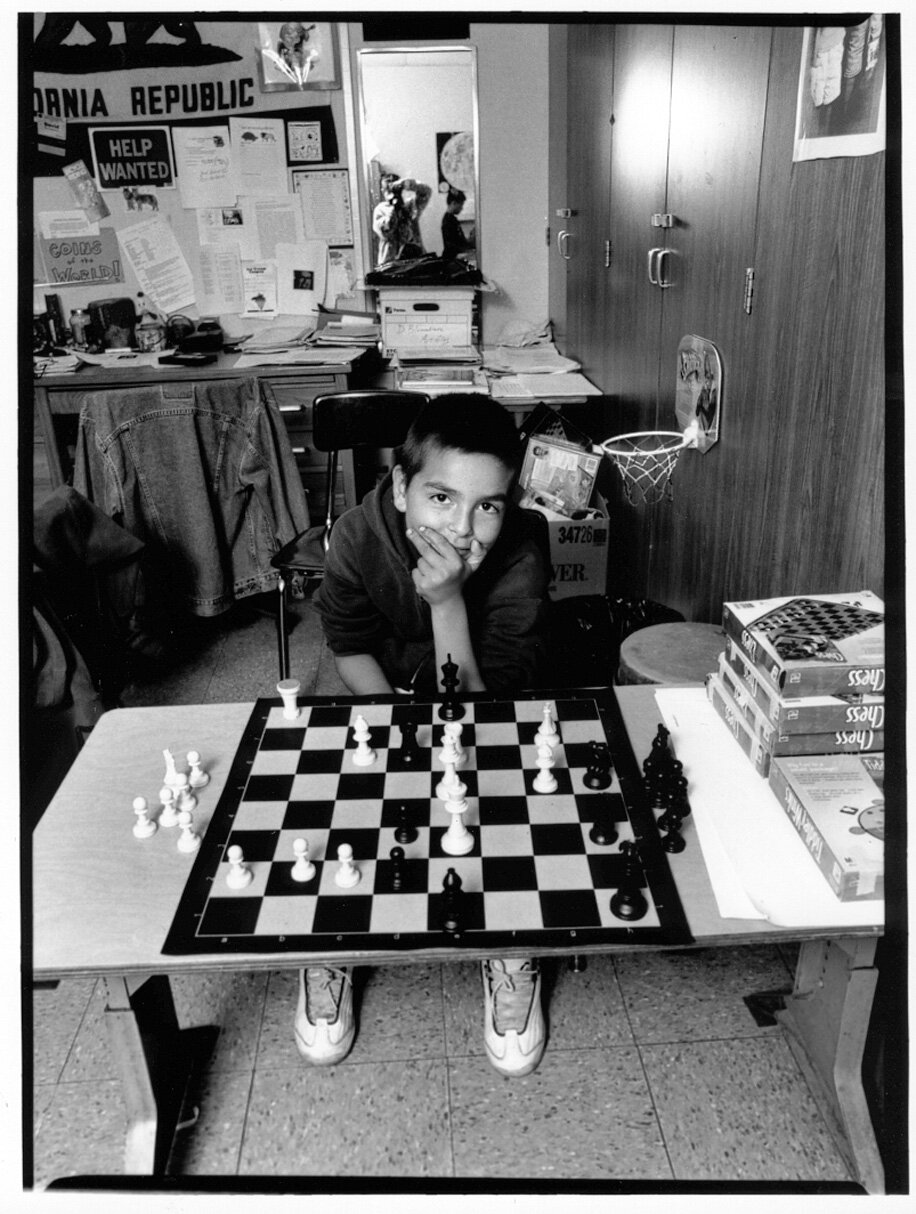

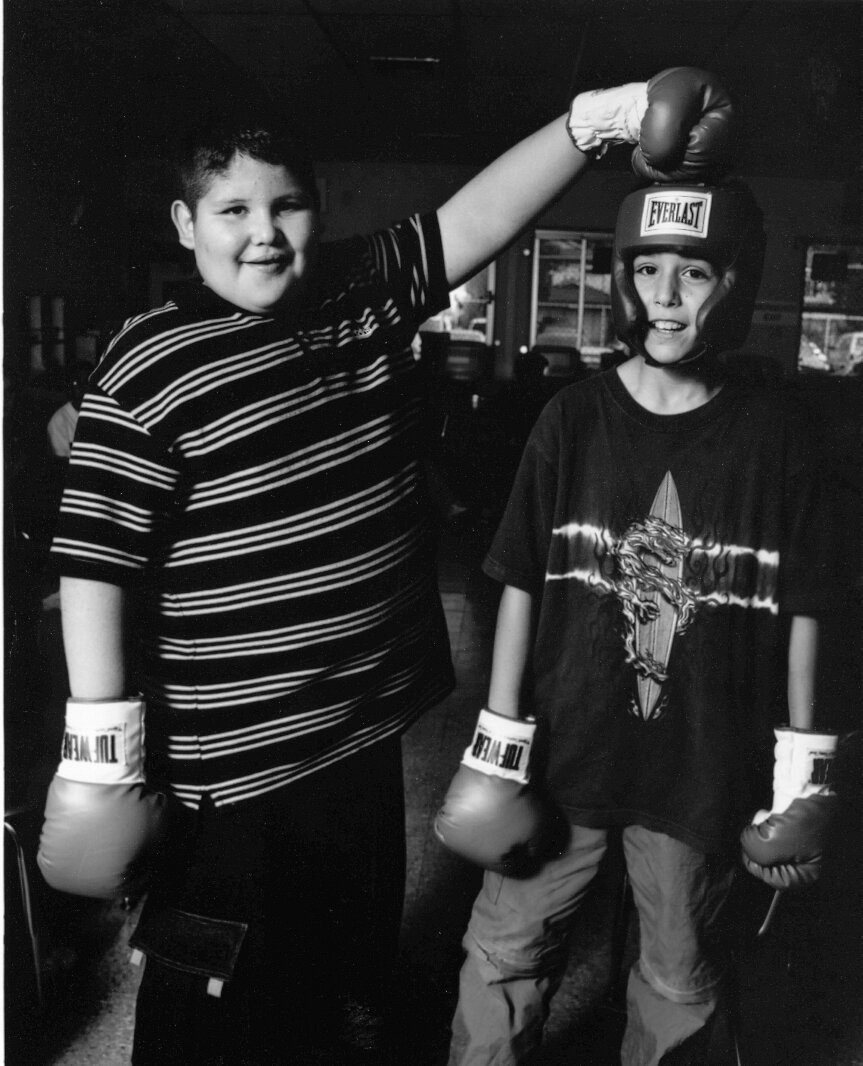

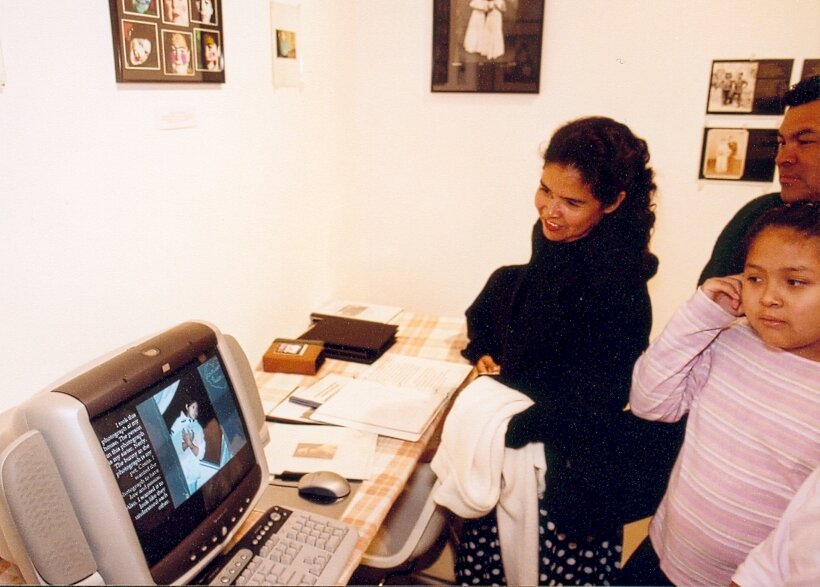

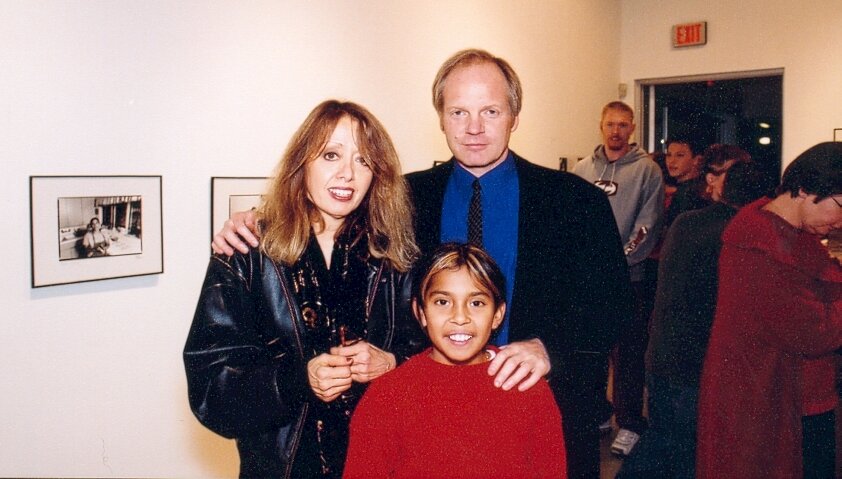

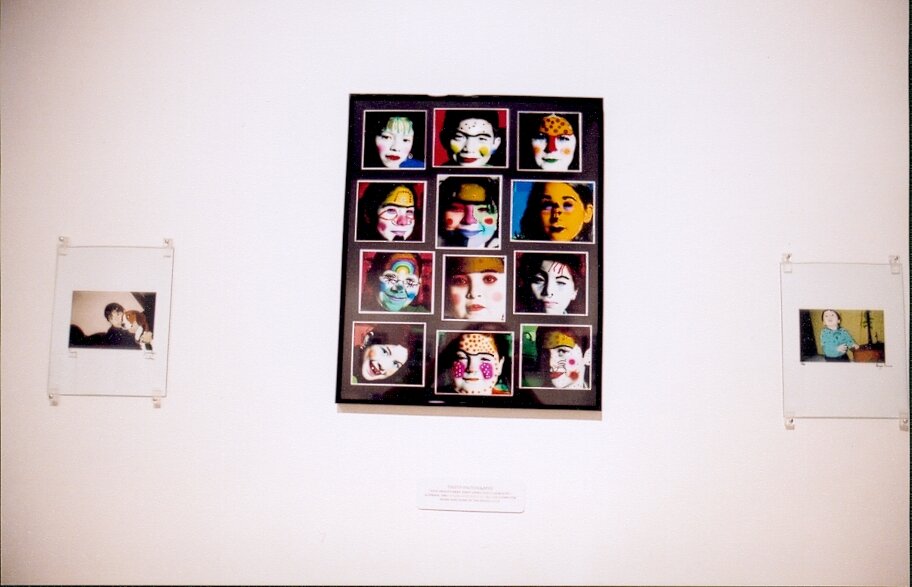

During our exhibition at CSUN, it was especially gratifying to see how the Treasures entries were appreciated by the viewing public. “The Way We See It” opened on a Friday evening, coinciding with the opening in the Main Gallery of a much larger, previously scheduled exhibition of art done by high school students in the area. This was good fortune: our elementary school photography served as a perfect counterpart to the work done by the older students; it also assured that there would be a huge turnout. It was estimated that as many as 500 people came through the galleries, and my students, along with their proud parents, found themselves on the receiving end of an long string of compliments and questions. Eight of the ten students made it to opening night, with one parent getting lost with the other two (Figures 38-41). The exhibition was scheduled for a week during our off-track time, and for each of the next five days, at least two of the students would spend time at the gallery, answering the questions of the occasional visitor. While much of the quiet time was spent playing our favorite “brain-stretcher,” chess, I threw one last writing activity at them, soliciting their impressions of the exhibition. Jennifer Lobos, who emerged as a leader during the course of the project, creating the original designs for our PowerPoint presentation and CDRom, wrote: “My parents loved it. They said it was fantastic, and that all our hard work paid off.” When asked which part was their favorite, the answers varied. Jennifer picked the “family treasures, because you get to see why certain photographs are special.” Nathan Alexander, along with Bryan Merino, Eva Sanchez and Grecia Vasquez, chose the black & whites, while others liked the “Crazy Faces,” a series of headshots tinted using the Adobe PhotoDeluxe software in our classroom’s iMac computers (Figure 42 also see appendix 5, page 62). When asked how the exhibit could be improved, a couple of the students thought it would have been better if we had included the actual, original photographs in the Treasures series, rather than scanned copies. Grecia wished we had displayed the photo collages and posters we’d created from the hundreds of color prints we accumulated. While I agreed in principle, I tried to explain the concept of “clutter,” and repeated the mantra my thesis committee members had impressed upon me: “less is more.” Nathan and Carlos thought the walls should have been painted black, while Kimmy and Jennifer both agreed that everything was great just the way it was. The university students, professors and administrators who visited the exhibition during its six-day life, universally shared this opinion. The compliments, particularly those of the university president, and the respective Chairs of the Mass Communications and Art Departments, served as a confirmation of sorts. Art Education programs such as this can be effective and useful, both in terms of pure curriculum design, and most importantly, as a method for creating a dynamic, working relationship between the school and the community it serves.

Selections from this exhibition were later put on special display at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles.

POSTSCRIPT: REFLECTIONS ON WORKING WITHIN THE LAUSD

As successful as this project appears to have been in the eyes and minds of the students, their families, and my colleagues and mentors at the university level, it is also important to reflect on what may have gone wrong. Looking back, it seems that any downside to the experience can be attributed to its being orchestrated within the context of the public school system, specifically the Los Angeles Unified School District. It’s no secret that public schools are currently mired in a dispiriting, obsessive quest for higher standardized test scores. This obsession has resulted in an ever-increasing emphasis on assessment, particularly in language arts and math. Teachers are now required to teach from mandated, scripted lesson plans and follow strict pacing plans. An inordinate amount of time in the classroom is spent on this — more than four hours per day. The situation is exacerbated by the need to prepare for the continuous onslaught of exams and writing assignments that are used, it would seem, to assess the progress of the school more than the individual child. While all teachers understand the need for assessment, the current climate is counterproductive. Teachers are openly expressing their frustration, as it has reached the point where we spend so much time administering assessments, that we don’t have the time to teach the material that appears on those very tests.

Eva, Grecia and Kimmy present a lecture on Lewis Hine to an Art class I was teaching as an adjunct at CSUN.

This being the case, it is nearly impossible to go into depth on any subject outside of language arts and math. Most teachers at my school have completely abandoned the use of the social studies textbook. Like all teachers, I feel this crunch, and suffer because of it, along with my students. But like all teachers who are more interested in the well-rounded education of their students than assessment numbers, I manage to find ways to cut corners out of the scripted pacing plans. My students have read most of their social studies textbooks, and I use the questions at the end of each lesson as an opportunity to teach essay writing. This enhances both their critical thinking skills and their understanding of historical and social context.

Similarly, subjects such as science and art are squeezed into the curriculum only as time allows, or as with this photography project, as special “differentiated curriculum” programs for the GATE students. It took a delicate balancing act to steal time from other activities in order to teach photography to these ten children, while finding equally interesting activities to occupy the rest of the class. As much as possible, I would include the entire class in the photography lessons. They would share in watching the slide shows, for example, and the entire class was invited to bring in old family photos for the Treasures activity. For the past two years, the whole class has also participated in the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Cal Art Start program, which provides an excellent, comprehensive curriculum (incorporating language arts activities) to go along with regular museum visits. One month after our CSUN exhibit, the Photography Club members and their families were thrilled to see their work on display for an afternoon at MOCA.

In-depth art education projects such as this may be hindered not only by time constraints or issues of inclusiveness, but also by a shortsighted brand of bureaucratic conservatism that prefers to err on the side of caution. One example should serve as a sufficient illustration of the way a reactionary, overly cautious mentality can undermine attempts at progressive curriculum. One of the Photo Club students had trouble meeting his deadlines and responsibilities. During the time I was making the home visits, there were some scheduling problems, and although I had been to his home in the past (and since), the Collaborations session was missed. When his mother complained that I was playing favorites with the students whose homes I had entered to take photographs, I was given an oral directive by my principal, after her consultation with district officials, to stop visiting students’ homes to take photographs! I explained that the project was essentially finished, and that the photo sessions had ended four months earlier. Nevertheless, the directive was put into a written memo. I expressed my concern that this kind of arbitrary issuance of directives, based on the heresy complaint of a single parent, could only discourage future attempts at creating curriculum designed to foster close collaboration between parents, students and teachers.

Another postscript of interest concerns the appearance of iconography in these photographs. I was contacted by an old friend who works in the LAUSD “Career Ladder” recruitment office in downtown Los Angeles. Though unaware of the work I had been doing with these children, he was looking for photographs to decorate their new office building. An arrangement was made which resulted in nearly 75 photographs (a combination of mine

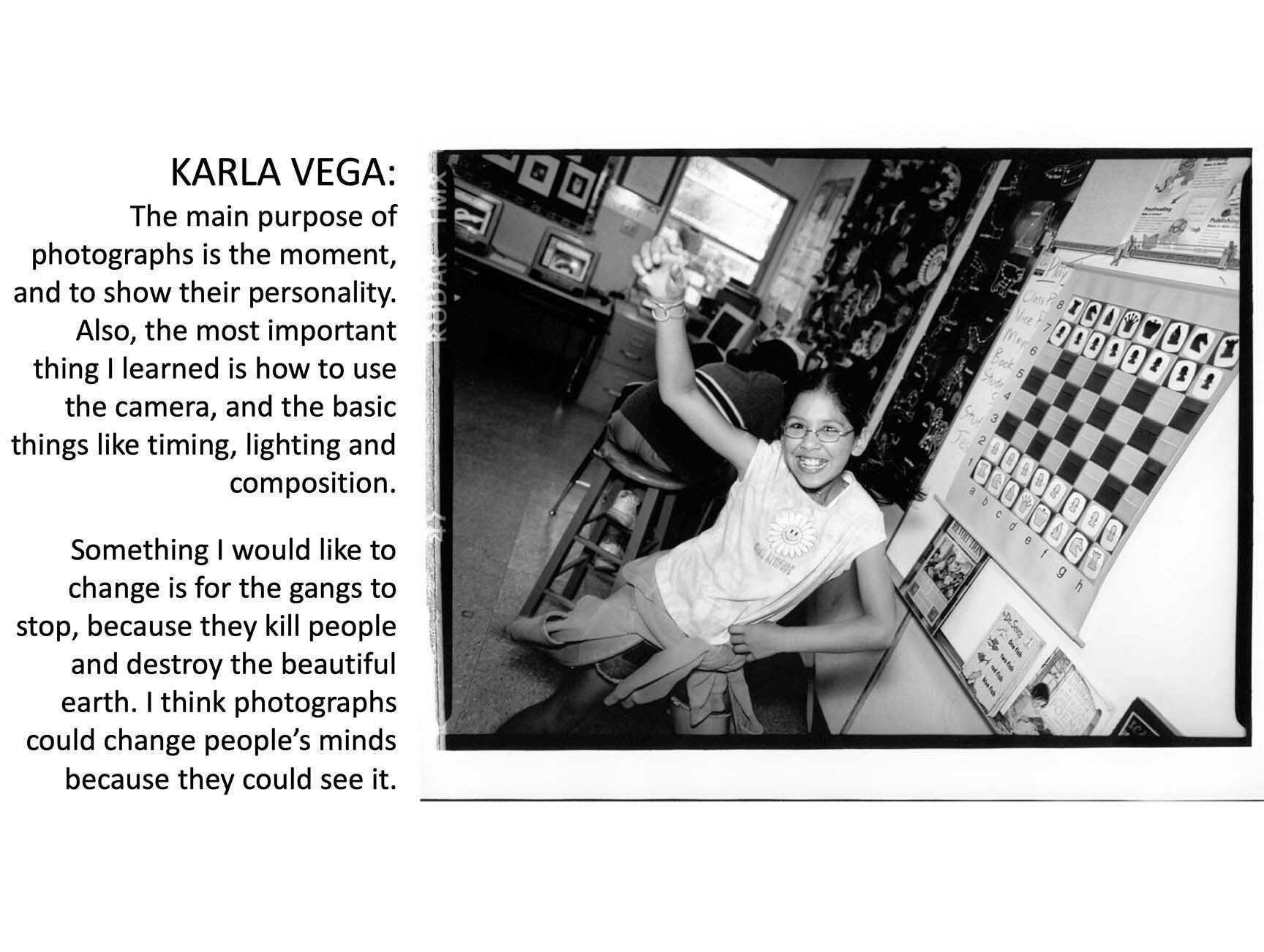

and the students’ work) going on display. Two of my photographs were rejected as being too “controversial.” One showed Karla in her communion dress, sitting with her grandmother and mother under a crucifix in her bedroom; the other showing Kimmy with her sister, looking very grim as she held an Osama bin Laden dartboard.m Such images wouldn’t be appropriate I was told, for display in our recruitment offices. While fully cognizant of the sensitivity surrounding religion in education, it never occurred to me that a photograph such as the one of Karla would be considered problematic. The vast majority of my students come from Catholic homes, as do a large proportion of the families in the predominately Hispanic school district. I have trouble understanding how a photograph that depicts a custom so ingrained in the cultural fabric of the community

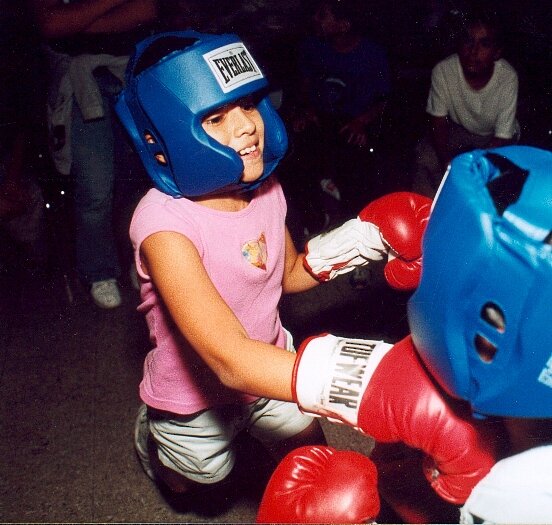

I was less surprised that the Osama bin Laden photo was singled out. I can only surmise that it points to the district’s lack of a sense of humor. More importantly, it represents an underestimation of (or an unwillingness to acknowledge) a child’s potential for social consciousness and innate awareness of iconographic satire. After reading a critique of our exhibit, written by an art student (and future elementary teacher) at CSUN, it’s not difficult to see how prevalent this misunderstanding can be. Of the “Osaka bin Laden” (sic) photo, the university student wrote, “I am curious to know if she really comprehends the politics that are alive in her country. I believe she knows who this man is, and that he is a ‘bad man,’ but I wonder if she really knows the reality of the world she lives in.” She goes on to wonder how this photograph came to be — who put the bin Laden image in her hands? “I wonder if it was their decision or the decision of the photographer . . .” She eventually contemplates the possibility that children learn of such things from television and other media sources, but never quite makes the connection that it is possible for a girl like Kimmy to have an aversion, however superficial or naïve, to repulsive political characters and events. The dartboard, which had many holes in it, belonged to Kimmy.

One final note—in preparation for our exhibition, I contacted the art advisor for our local District C office, to extend a personal invitation. Her appearance at the opening reception was strangely brief. She never spoke with any of the students about their work, nor did she approach me with any comments or inquiries about the project. I found this lack of curiosity, from a person designated as an “art advisor,” to be odd. Aside from the Career Ladder office, whose use of our photographs came about incidentally, in the months since the exhibition, no one in the school district has contacted me. Happily, on the day before they were to graduate from Kittridge St. Elementary, my students, their families and I were invited to a special ceremony to recognize the work of these young photographers, whose art went on display, on the fourteenth floor of a Los Angeles skyscraper, the home of the LAUSD administrative offices.

CURRICULUM

PHOTOGRAPHY AS EDUCATION: GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

This project was designed to meet the LAUSD requirement of providing a differentiated curriculum for students in the Gifted and Talented (GATE) program. In this specific case, there will be nine fourth-grade students participating in the “Photo Hobby Club.”

There are serious time constraints and difficulties inherent in trying to facilitate this type of activity in concert with usual class activities and curriculum. The activities in this project will therefore be largely worked on at home. Meetings will be held during school time to explain the assignments, and the students will be allowed to work on their photo albums and computer work during afternoon “free-time" sessions, as well as after school when possible.

This project has been specifically geared toward meeting the Goals and Objectives decided on by our school this year:

GOAL II: CREATIVE THINKING

Objective 8: Pursues hobbies and interests

Objective 27: Demonstrates creativity unique to the individual when doing an assignment.

EVALUATION METHOD: A combination of observation and student portfolio review. (This includes both teacher and peer analysis of finished products: i.e.; photo albums and PowerPoint projects).

STANDARDS: Computer Technology

DIFFERENTIATED STRATEGIES: The students will be taught the basics of photography, and will use 35mm cameras, computer scanners and the multi-media program PowerPoint to develop their photographic skills and interests. This project also includes a writing component. Students will be introduced to vocabulary terms relevant to the medium of photography, and will be expected to use them appropriately as they learn to write critically about photography, and art in general. In addition, they will research and write a report on a photographer of their choice (see Goal VIII below).

USE OF TECHNOLOGY/RESOURCES: The students will use their cameras, our classroom scanner and computers to complete individualized presentations.

GOAL VIII: ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE:

To achieve and maintain academic performance levels commensurate with expectancy (working two years above grade level or beyond the 89thpercentile and above on the STAR or other norm-referenced assessment).

EVALUATION METHOD: Rating scale (rubric, similar to the one employed during Performance Assessment exercises). Peer evaluation and teacher observation will be used for oral reports.

STANDARDS

WRITING

Writing Strategies 1.0: Students write clear, coherent sentences and paragraphs that develop a central idea. Their writing shows they consider the audience and purpose. Students progress through the stages of the writing process.

ORGANIZATION AND FOCUS

1.2 Create multi-paragraph compositions

RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY

1.6 Locate information in reference texts

1.7 Use various reference materials

Listening and Speaking Strategies1.0: Students listen critically and respond appropriately to oral communication. They speak in a manner that guides the listener to understand important ideas by using proper phrasing, pitch, and modulation.

DIFFERENTIATED STRATEGIES: Students will create research reports about a famous photographer, using multiple sources of information, and will be able to write a bibliography citing these sources. The reports must demonstrate full knowledge of the writing process, the use of reference books such an atlas, thesaurus, encyclopedia, and computer technology. In addition, the students in the program will deliver oral presentations, summarizing their findings and will be graded on four criteria: completeness of report; clarity of delivery; eye contact with audience; and the ability to field follow-up questions from their classmates in the audience. Therefore, this also entails good listening skills by those in the audience, and the ability to respond appropriately to oral communications. Visual aids (such as 35mm slides, which will be created by the instructor), should accompany the oral presentations, and the students will be expected to explain the photographic images using the appropriate terminology.

USE OF TECHNOLOGY/RESOURCES: Internet, Encyclopedia CD-ROMS, and library reference materials.

GOAL VI: VISUAL ARTS

Objective 30: Analysis: Infers abstract meaning in visual symbols.

Objective 33: Draws, paints or sculpts things in ways few others do and in ways not usually taught.

EVALUATION METHOD: Combination of observation, and student portfolio review. (This includes their Photography Workbooks, Photo Albums, and PowerPoint presentations).

STANDARDS: Visual Arts Goals, Creative Expression Component:

Goal 3: Students develop knowledge of and artistic skills in a variety of visual arts media and technical processes.

Goal 4: Students create original artworks based on personal experiences or responses.

DIFFERENTIATED STRATEGIES: Our class is participating in the Museum of Contemporary Art’s “California Art Start” program, which emphasizes contemporary/modernist abstract genres of art. The students will be creating “action paintings,” video art, sculptures, and other art forms, with activities that focus on abstract conceptualization, design and implementation.

One particularly unique assignment, given to the students in GATE, will be the creation of “combines,” in which the students will use objects found in everyday life, and combine them with photographs, painting, and other items to create three-dimensional art objects, similar to the style made famous by Rauschenberg. In addition, we will be making two trips to MOCA (one has already been done, and the other will come in April, funded by MOCA), and one visit to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to see the exhibition of modern American art. The students are keeping “Art Journals” throughout the year, in which they are allowed to express themselves in unconventional writing styles.

USE OF TECHNOLOGY/RESOURCES: The students will do research using the Internet and CD ROM software programs.

MATERIALS NEEDED FOR THIS PROJECT INCLUDE:

10) 35mm (automatic) cameras

30) rolls of ASA 200 color film

Photography Workbooks

materials to create photo albums

Computers with PowerPoint multimedia software, scanner

slides of photography history, examples of different types of photography

REFERENCE SOURCES/CORE LITERATURE:

Gibbons, Gail. A Book About Cameras and Taking Pictures. Little, Brown and Co., Boston. 1997.

Varriale, Jim. Take A Look Around: Photography Activities for Young People. The Middlebrook Press, Brookfield, Connecticut. 1999.

Using Cameras in the Curriculum. Eastman Kodak Company, New York, 1994.

ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITIES ARE LISTED HERE IN APPROXIMATE CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER, ALLOWING FOR FLEXIBILITY.

ALL ACTIVITIES TO BE DONE IN THE STUDENTS’ “PHOTOGRAPHY WORKBOOKS” ARE MARKED WITH A “W.”

1) Introduction to Photography: Slide presentation showing brief history of photography, and some of the ways photography has been used (art, journalism, science).

2) What is Photography? (W): Students write a short essay about photography, based on their personal opinions and observations.

3) Introduction to the Camera/Vocabulary List #1 (W): Students are taught the various parts of the camera, and how they function. This includes a vocabulary list.

4) Photography as Art—Elements of Good Photography/Vocabulary List #2 (W): This includes a slide presentation, during which the students are asked to identify how lighting, timing, and composition are used by the photographers to make the photographs more effective.

5) Art Analysis and Criticism Exercise (W): Students will be comparing and contrasting a Cubist painting by Picasso, with a “Social Realism” photograph by Lewis Hine. They will be encouraged to use as many of their vocabulary words as possible.

6) FIRST PHOTO ASSIGNMENTS: The students will be instructed on proper camera care and usage. They will then be given two weeks to shoot their first roll of film, with specific objectives in mind. These include: camera angle, shadow and lighting, frame and scale, composition, action, the moment, and mood. They will be asked to capture as many of these qualities on their roll of film as they can. Their workbooks include descriptions of each of these assignments.

7) Scanning Photographs: Students will use the classroom scanner to enter all of their best images into their personal files, for later use in Multi-media presentations.

8) Dorothea Lange Biography (W): Students will read the biography of Dorothea Lange, and will watch a slide presentation of some of her most important work, after which they will answer some questions about her life and work.

9) Photo Albums: Students will create their own personalized photo albums, for storing their prints. (Prints can only be glued into the albums after they have already been scanned).

10) Black and White or Color? (W): Students will explore the similarities and differences between black & white and color photography, using the Venn Diagram in their workbooks.

11) Positive and Negative Space (W): Students will use black construction paper to create a design which emphasizes positive and negative space.

12) SECOND PHOTO ASSIGNMENT (San Fernando Mission): This assignment integrates this project with the fourth-grade Social Studies curriculum. On a field trip to the San Fernando Mission, the students will be looking for images that reveal interesting compositions and lighting. Most significantly, they will be looking for interesting physical characteristics and details of the mission that could be photographed to illustrate the historical importance of the mission. Additionally, this second roll of film will be used to shoot portraits of their classmates.

13) A Photo that Captures My Imagination (W): Students will be given the assignment of finding a photograph in a magazine that “captures their imagination.” They will write about the photograph on the page in their workbooks. This is designed to increase their observational and critical thinking skills.

14) Describe This Photograph! (W): Students will each be given one photograph to study and write about. Again, they are encouraged to use their newly acquired vocabulary words.

15) PHOTOJOURNALISM: Interview with Family Member (W): The students will choose one member of their family to interview and eventually photograph. They will create at least four questions and record their answers in their workbooks.

16) THIRD PHOTO ASSIGNMENT: PORTRAITURE: The students will view a slide presentation showing the various styles of portraiture, with an emphasis on the environmental portrait. They will use most of this last roll of film photographing the family member they interviewed, but will also make images of other family members.

17) Biographical Sketch (W): Students will write a series of paragraphs about themselves, their families, their communities, and their thoughts about photography.

18) Research Report: Biography of a Photographer (W): The students will be given a list of photographers to choose from, and will instructed to write a 3-5 page biography on that artist. They must use at least two sources of reference (one of which should be either from the internet or a CDRom). The report will include samples of the photographer’s work, and a bibliography. The students will then make oral presentations to the entire class.

19) CULMINATING ACTIVITY: PowerPoint Presentations: The students will create multi-media “photo-albums,” showcasing their favorite photographs. These will be customized to the students’ own design specifications—the only firm requirements will be that they include at least 5 photographs, text, animated images, and sound. These will then be burned onto CDRoms.

20) Final Thoughts on Photography (W): In this final workbook entry, the students will compare what they now know and think about photography with their perceptions at the beginning, as recorded in Activity #2, What is Photography?

VOCABULARY LIST #1: THE CAMERA

Camera: a light-proof box used to record images on film. The word camera comes from the Latin term camera obscura, which means “dark chamber.” No light can get inside a camera except when a picture is being taken.

Lens and Aperture: The lens of the camera is very much like the human eye. It has an adjustable opening called an aperture, which is like the iris of our eye—it opens and closes depending on how bright the light is. Without a lens it is impossible to take a sharp photograph.

Viewfinder: The viewfinder is the tiny screen you look through to compose your image. Remember, whatever you see in the viewfinder will end up on your film, so be careful to make a good composition.

Shutter: the shutter is like a shield that protects the film from light. When you push the shutter release button to take a picture, the shutter opens for a fraction of a second, allowing light to pass through the lens and onto the film.

Exposure: When you open the shutter, you expose the film. Each image you make is called an exposure.

Film and Emulsion: Film is sheet of plastic coated with a light-sensitive material called emulsion. When the shutter is opened and light enters the camera, the image that the lens sees is “burned” onto the emulsion of the film. Only when the film is actually developed does the image appear, as a negative.

Film Advance Lever and Frame Counter: Unless you have a camera that automatically advances your film after each photograph, you must wind the film forward using the film advance lever. All cameras also have a frame counter, which tells you how many pictures you have taken, or how many are left.

Film Speed: Film is made in different “speeds,” measured in ASA numbers. The “faster” the film, the more light the emulsion can record. The larger the number, the “faster” the film is. For example, you can use a film rated ASA 100 outdoors in bright sunlight, but when you take pictures indoors where there is less light, you might want to use an ASA 400 film.

Flash: A flash is an artificial light which is either built-in to the camera, or can be attached to the camera. The flash is used when it is too dark to take a photograph without one.

Back Door Release Button: This is how you open the camera to load or remove your film.

Film Rewind Button: Usually located on the bottom of the camera, this button must be pressed before you can rewind the film back into its cassette without damaging it.

VOCABULARY LIST #2: ELEMENTS OF GOOD PHOTOGRAPHY

Lighting: The word photography comes from the Greek words meaning “writing with light.” Taking a photograph is like drawing a picture using light as your pencil or paint. Photographers are always aware of where the light is coming from, how bright or dull it is, where the shadows are, and how it will look in the finished photograph.

Timing: The invention of photography allowed artists to capture a moment in time, and to freeze it forever. Therefore the moment that you snap the shutter is very important. This is true whether you are photographing sports action, or just taking a portrait of a friend. Try to time your photos for the exact moment you want.

Composition: When you look through the viewfinder of your camera, whatever you see will end up on your finished photograph. This viewfinder is just like the canvas the painter uses. Therefore, try to arrange all the elements in your sight into a composition that you like, just as you do when you are drawing or painting.

Proximity: The word proximity means “closeness.” In other words, the distance between the camera and the thing being photographed is also very important. Photographers that are too shy or in a hurry sometimes don’t get close enough to their subject. The camera is an amazing tool for recording details (such as texture), but if you are too far away then the camera can’t do its job!

Angle: The position of your camera in relation to the thing being photographed is the angle. By changing the angle, you can change the effect of the photograph. For example, by photographing something from beneath it, that thing may appear stronger and more powerful. If you look down on something when you photograph it, the thing you photograph will appear smaller or weaker.

RESEARCH REPORT: BIOGRAPHY OF A PHOTOGRAPHER

Choose one of these photographers to research and write about:

Lewis Hine (Children and Work)

William Wegman (Dogs)

Ansel Adams (Nature and the Environment)

Edward Curtis (Native Americans)

Eadward Muybridge (Studies of Motion)

Julia Margaret Cameron (Portraits)

This report must meet the following goals:

1) At least 3 pages long

2) Double-spaced

3) Written in cursive or typed

4) At least two sources of reference—one must be a book, the other from the computer (either internet or CDRom)

5) Bibliography

6) Cover with one of the artist’s photographs

7) Other examples of their photographs

8) One example of “Analyzing Works of Art.”

The report should answer the following questions:

1) Where and when the photographer was born.

2) Why this person became a photographer.

3) What kind of photography did this person specialize in?

4) What kind of cameras or film did they use?

5) What is this person most famous for?

6) How is this person’s photography different from others?

7) Why did you choose this person—what is it about their photography that you like so much?

Finally, you must choose your favorite photograph by this artist, and analyze it using the paper “Analyzing Works of Art.” This should be included at the end of your report, before the bibliography.

This report is due on _________________________________________