Thirty Tons of Soil: Nanyonga's Divine Panacea

(November, 1989)

By David Blumenkrantz

“People are dreaming if they believe that Nanyonga’s soil will solve their problems. It is true that there are natural remedies that help many infections. Quinine from the bark of the chinchona tree can cure malaria, and various herbs can help heal wounds and kill infections. There is even a type of soil, kaolin, a chalky clay, which helps bind the stomach when people are suffering from diarrhea. But there has never been any drug that can cure all diseases. What a wonderful thing that would be!”

Editorial, The New Vision, November 11, 1989

This is the bizarre tale of Nanyonga, an elderly peasant woman who for a period of several weeks both outraged and comforted Ugandans and Africans from neighboring countries with a divine panacea of soil and water. Nanyonga claimed that on the night of September 8, she had been visited and instructed by God (in the form of a blinding light and mysterious voice) to cure all manner of illness by merely feeding them the blessed soil from her shamba. The dedication and zealousness with which this self-proclaimed lifelong Catholic and her supporters took up this task transformed a sleepy, obscure village located near Ssembabule in Masaka District into a circus of hawkers, government investigators, curiosity seekers, and most importantly, a multitude of believers.

For several weeks, Nanyonga was a media sensation in Uganda. There had been accounts of well-known herbalists claiming AIDS cures before her, but Nanyonga represented something less acceptable than traditional medicine. Accounts of her purported faith healing exploits dominated the headlines and editorial pages of newspapers, where she was widely excoriated for everything from peddling false hope to ignorantly putting those who ingested her soil at real risk. The Weekly Topic, one of Uganda’s two major daily newspapers, editorialized:

“The whole thing reeks of forgery and deception on a large scale. For what is in mere soil and water to cure AIDS? Nothing. But why have so many Ugandans including otherwise enlightened ones been taken for a ride and fallen prey to this deception? The answer lies in growing desperation and despondency amongst the ever growing number of AIDS victims as a possible cure continues to elude even the world’s top scientists.”

The editorial criticized high-ranking government officials, who rather than offering guidance to those with ‘average and simple minds,” went themselves for the soil, “hence perpetuating people’s belief in this falsehood.” This belief had begun with the story of Nanyonga’s niece Margaret Nazziwa, and her supposed amazing recovery from the symptoms of AIDS. Newspapers reported that Nazziwa had been at the brink of death before becoming the first to benefit from the divine soil. She had reportedly been treated at a Kampala hospital, was bed-ridden and could not eat or drink before digesting the mixture of soil and water. Nazziwa’s story was from the outset refuted by some local villagers. The controversy intensified when the girl, who apparently started living it up too heartily, died suddenly of heart failure, coughing up blood. Nanyonga’s supporters blamed the tragic demise on the niece’s lack of faith and her wanton lifestyle.

Aside from the case of Nazziwa, there were at least as many reports of people becoming ill or even dying as there were of definite cures. This caused the Ugandan authorities much consternation, especially those charged with educating the people about the scientific findings on AIDS, and abandoning old habits, particularly promiscuous, unprotected sex.

The media prodded the government into action, criticizing the AIDS Control Program for not acting quickly and decisively to counter Nanyonga’s impact. The Weekly Topic reported that on October 26, Uganda’s Minister of Health finally sent a high-powered delegation to visit the site. Not surprisingly, the medical team established that the soil “does not immunize or cure anybody against any disease.”

Regardless of media and government condemnation, Nanyonga’s pull among the common folk was phenomenal. Whatever the validity of her claims might have been, she had tapped a very sensitive nerve in the public's desperation for salvation, at a time when the Ugandan government was fighting an uphill battle in AIDS education and awareness. By 1989, AIDS had reached epidemic proportions in Uganda, leaving thousands dead and entire villages decimated. Uganda was at the forefront of AIDS education in Africa, and groups like The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) were training counselors to work with victims and their families. In April, while interviewing various TASO officials and trainees, I first learned of the difficulty people had in choosing science over spirituality. Counselor trainee Lubuye Erasmus recalled how in 1983 he had taken his brother-in-law to a witchdoctor: “I found myself taking him there! We were treating the disease, and it was not going. To be sure, if somebody said, ‘I can treat that disease,’ being a witchdoctor or not you would go there, if he is providing a remedy.”

Hysteria ensued when rumors began circulating that people known to have AIDS had recovered after drinking Nanyonga’s soil and water cocktail, another man who had been using crutches had thrown them away, and a small child with stomach problems had been cured. Rich and poor, believers from all walks of life came in droves. This included policemen, soldiers, members of all religious sects, and even government officials. Seeking cures for every illness imaginable, it was widely reported that lines consisting of thousands of people stretched more than two kilometers from outside her humble compound. Seeking only a few scoopfuls of the blessed dirt, the hopeful arrived not only from within Uganda, but from bordering countries such as Rwanda and Zaire. People were apparently willing to wait several days for their turn. Opportunistic hawkers set up shop all along the route, selling everything and anything one might need. The sounds of the open marketplace filled the air, as did the smells of roasting meat, boiled matoke bananas and peanut sauce. Corrupt officials profited by collecting the “medicine” for car owners who couldn’t drive up to the “treatment site.” At times, the mob would become unruly. There were reports of people suffocating in the crush. The Independent Observer reported on October 26 that Nanyonga had “mysteriously escaped death” when a grenade was tossed at her from the crowd. One front page headline screamed: “Sheer madness: Another ‘Lakwena’ in Masaka.” (Lakwena was the leader of the rebel faction Holy Spirit Movement, whose fanatical quasi-religious beliefs convinced her out-manned soldiers to spread bulletproof oil on their bodies before sending them to their death against government troops. In 1988 she escaped into Kenya, where she was apprehended and jailed for immigration purposes).

A BAG OF DIRT

Word of Nanyonga’s exploits reached Nairobi, where I was preparing another trip to Uganda to cover relief projects for InterAid. Arriving in Kampala, it didn’t take much to convince my friend Boniface, who worked as a driver, that we should go rouge and commandeer a company Land Rover. Early the next morning we headed out west to find the village. Boniface was just as curious as I, and as we navigated our way through the endless succession of small rural towns, it became clear that his curiosity was born of less skepticism than my own. Boni was holding out hope that Nanyonga’s magic was for real.

Six hours after leaving Kampala, we finally arrived in Ssembabule, and from there it was only a short drive on uneven dirt roads to Ntuku. Arriving at her compound, it was immediately evident that Nanyonga's heyday had passed. There were only around sixty people faithfully waiting in the makeshift runways that had been erected, similar to the type built to channel cattle into a kraal or a dip. The atmosphere was surreal, like visiting an amusement park on a slow day, when the lines are shorter than usual. Whether her diminished popularity was the result of the government's strong anti-Nanyonga stance, the relentlessly negative media coverage, or simply because she had already accommodated the majority of those who would believe, was not clear.

Nevertheless, I found Nanyonga still at work, standing in the center of the gigantic crater she had dug over the previous few weeks. She was scooping out one spade full of the reddish dirt at a time, and depositing it into plastic bags and other containers held by the faithful. The circular pit was at least three feet deep, with a diameter of twenty feet or more. In the span of little more than one month, she had reportedly given out thirty tons of the panacea to the sick and infirm.

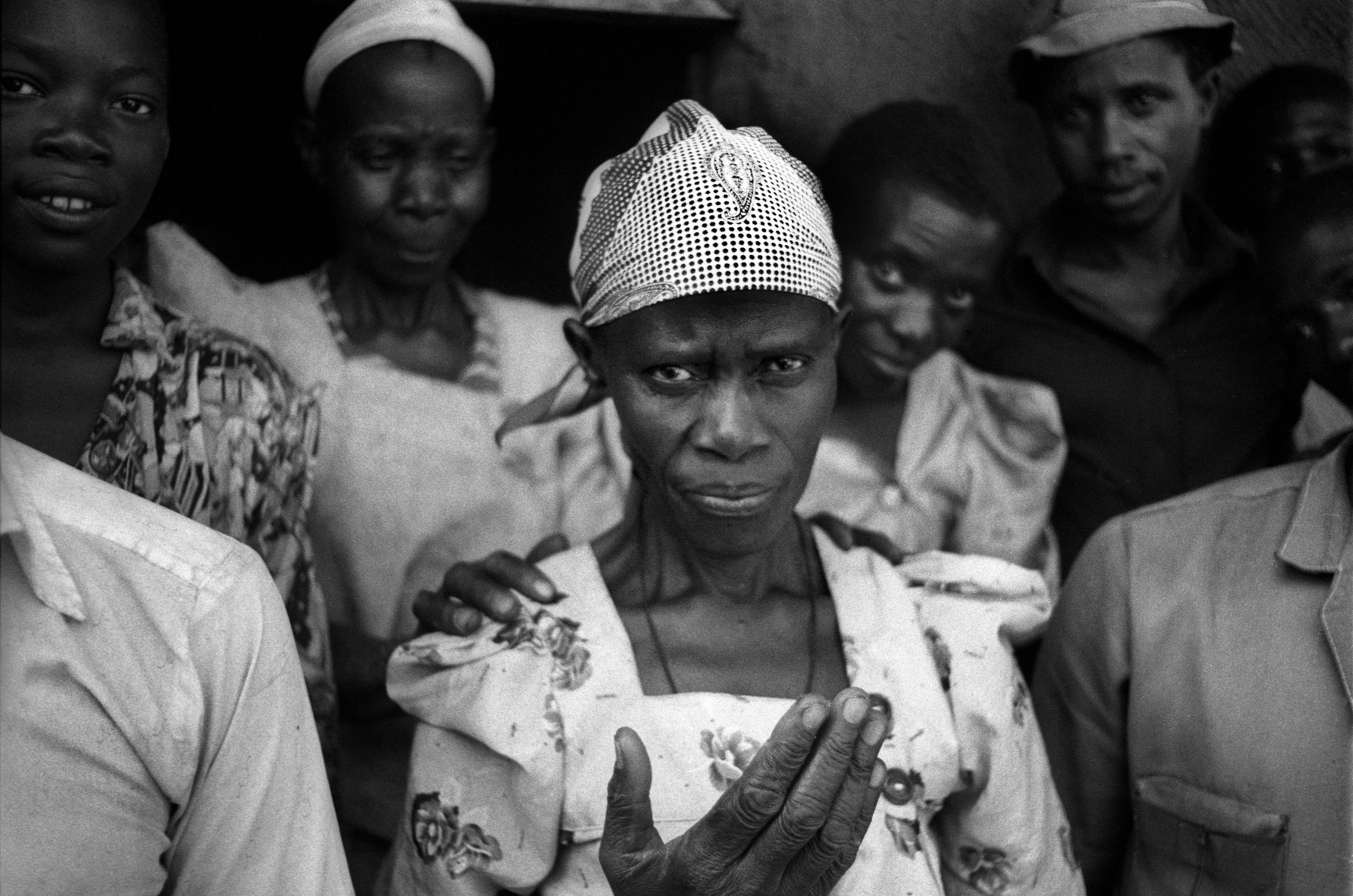

Her house was simple mud and wattle, though there was a group of men busily working to build a small addition. I was led to a rickety bench and invited to sit. When told I wanted to speak with her, Nanyonga came out of the pit and knelt next to me, head down in the traditional Ugandan manner. She was very plain looking, like a woman from any market in East Africa. She wore typical peasant clothing: a torn and faded Kenyan lesso, simple shirt and a new white scarf with blue patterns. She looked perhaps a bit younger than sixty-five.

Either outwardly indifferent or perhaps impervious to the uproar she had caused, she seemed pleased and a little bemused that I had traveled from so far to meet her, but showed it in the humble manner of an elderly peasant woman: by silent acknowledgement, and an occasional shy smile. We conversed through an interpreter: she didn’t speak much Swahili. Her face revealed no sign of corruption or manipulative intent; aside from a fleeting mischievous glint, her eyes conveyed a great seriousness, as though she had been burdened with a crucible of such magnitude that she wasn't certain her mortality could sustain it without great faith. While speaking, she punctuated her words with pious hand gestures, as if to show her devotion to the God who had sent her on this mission. She granted me permission to take photographs, prompting one zealot to enthusiastically explain, "Your photographs will only come out if you ask permission to take them, otherwise not." I later discovered that this part of the legend came into play when, during the earliest days of Nanyonga’s notoriety, a mzungu (white man) had reportedly taken a number of pictures featuring the healer at work. When he attempted to develop the film, it was blank. As explainable as this may be (if in fact it’s true), it sent “powerful currents of vindication among the soil seekers and added more impetus to those who had yet to come,” according to The New Vision.

I was granted some sort of VIP status, and was allowed to cut to the front of the line. When I climbed down into the pit without taking off my boots, no one complained, even though Boniface had been thoroughly chastised minutes before for entering the sacred ground in his shoes. Nanyonga ceremoniously poured two handfuls of dirt into the plastic grocery bag I was holding, while her followers nodded approvingly. Through her interpreter, she repeated what I assumed was the same advice given to the thousands before me. The soil was to be mixed with cold water only. Boiled water would render it useless. I was also warned that there could be no financial transactions involved. "If you buy it and take it, you will not be cured," she intoned gravely. "If you sell the soil, you will go mad.”

FAITH, OR HYSTERICAL DISSOCIATION?

What really happened in that tiny village, which has since reverted to a state of tranquil anonymity? Was Nanyonga so in touch with the spirit world that a manifestation occurred somewhere in the shadows of her heart and soul? One could wonder if her feeding of soil was the only tangible, physical thing she could offer to the desperate thousands of sick, poor and curious. As easy as it seems to dispute her account of the divine visitation that set this extraordinary act of benevolence in motion, whether divine or misguided, experiences such as Nanyonga claimed to have had are not unheard of. An article published in the Weekly Topic on November 1 speculated that her experience “was a hysterical dissociation,” which can occur “in simple neurotic personalities with over-valued ideas and beliefs.” The article further states that while there is “no evidence that this woman was neurotic or fanatical,” Nanyonga may have been visualizing “the destiny of man after death in the light of cultural beliefs, religious doctrine and her own ideas. All these suggest that her vision is not divine but pathological.”

There’s also the possibility that Nanyonga was little more than a publicity seeking old woman, as the majority of the Ugandan press painted her. “Money is not everything, power is also intoxicating,” The New Vision editorialized. Who knows? Nanyonga, by all reports, never charged a cent for her services, yet at the same time didn't discourage the attention she received. Against reason, I found myself carrying my plastic bag of dirt back to Kenya. I tucked it away in a cabinet, where it sat for a year until I scattered it in my own shamba . . .